Nilofer Merchant is a master at turning seemingly wild ideas into new realities and showing the rest of us how we can do the same. Awarded the Future Thinker Award from Thinkers50 and named the #1 person most likely to influence the future of management in both theory and practice, Nilofer has been called the “Jane Bond of Innovation”—and for good reason.

She has personally launched more than 100 products, netting $18 billion in sales, and has held executive positions at everywhere from Fortune 500 companies like Apple and Autodesk to startups in the early days of the Web. Her ideas have been featured in publications like the Harvard Business Review, Forbes, and Wired, as well as in her TED Talk, “Got a meeting? Take a walk.”

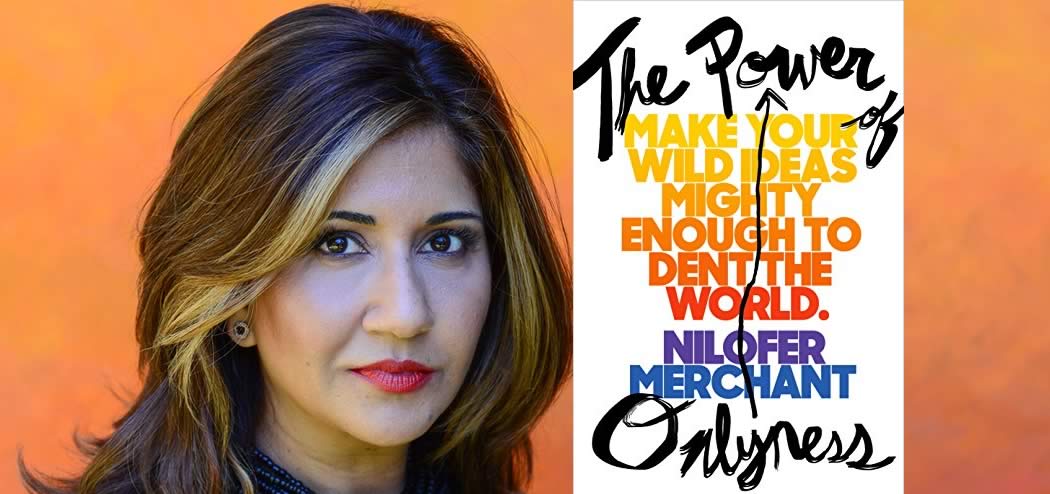

In this episode, Nilofer shares insider expertise from her new book, The Power of Onlyness: Make Your Wild Ideas Mighty Enough to Dent the World, and explains how we can connect our ideas to the world around us and create change.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How to find your “onlyness” and use it to make a difference.

- Common characteristics among pioneers and people who affect change.

- The important lesson Nilofer learned about coercive power.

- How our preconceived notions of power and qualifications hinder innovation.

- Where innovation truly comes from.

- What Nilofer says has become the smoking of our generation.

- How “regular” people can make a difference in the world.

Key Resources for Nilofer Merchant:

-

- Connect with Nilofer Merchant: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter | Facebook

- Amazon: The Power of Onlyness: Make Your Wild Ideas Mighty Enough to Dent the World

- Kindle: The Power of Onlyness: Make Your Wild Ideas Mighty Enough to Dent the World

- Audible: The Power of Onlyness: Make Your Wild Ideas Mighty Enough to Dent the World

- College Confidential

- “Got a meeting? Take a walk” TED Talk

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast, I’m Roger Dooley.

Our guest this week is a friend whom I’ve met several times, and who’s a super engaging speaker. Her TED Talk is the shortest one I’ve seen, running about three minutes, and is the only one I know of that uses the word “tush”.

Nilofer Merchant has personally launched more than 100 products, totaling an astonishing 18 billion dollars in sales. She’s had executive positions at everywhere from Fortune 500 companies like Apple and Autodesk, to startups like GoLive, which was later acquired by Adobe.

Nilofer, as an author, has written for Business Week, Forbes, Harvard Business Review, Wired, and even Oprah. Her new book is, “The Power of Onlyness: Make Your Wild Ideas Mighty Enough to Dent the World”.

Welcome to the show, Nilofer.

Nilofer Merchant: Thanks for having me, Roger.

Roger Dooley: It was great to see you in Orlando, Nilofer. I just missed running into our mutual friend, Dan Pink. I seem to be on a different speaking circuit than many of my guests, and it’s kind of strange to have so many friends that I’ve connected with only via social media and on the podcast, so it was great to see you, but I guess that’s the century that we live in, when our friends are more virtual than real.

Nilofer Merchant: Yeah, it’s actually a beauty of this age, is we can find the other people who care about the same things as us.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, definitely.

Your TED Talk is about five years old, now, Nilofer, but it still carries a great message about the importance of not sitting all day. In fact, as we speak, I’m standing, here. I changed my practice about a year ago to do all my recording standing up, and it offers really practical strategy for changing one behavior that just about all of us engage in frequently. Are you still doing the walking meeting thing?

Nilofer Merchant: In fact, I had one this morning. Yeah, so, it’s a great culture-hack right? Instead of doing meetings, sitting meetings, usually going to coffee shops or sitting in some fluorescent-lit conference room, to actually take the time to step outside and go for a quick walk around the block or in a park, or whatever. It started, for me, probably four years before I ended up doing the TED Talk on the topic, and in fact, Roger, you’ll find this amusing, when I got asked to give the talk, I was like, “You know, this doesn’t seem that new of an idea, the idea of walking and talking.” But the team who was curating for TED said, “No, actually, no, it could really be a big social change.”

The talk, of course, has gone on to be quoted quite a few times. In fact when Tim Cook introduced the Apple Watch feature that reminds you that you’ve been sitting for too long, he actually used the same phrase as I did, and my son was so proud, because he’s like, “Look, you’ve changed society.” If Tim Cook can say this phrase, “Sitting is the smoking of our generation.” to introduce a watch in front of literally hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people, to stand up more, it’d be a really small idea that can make a huge difference.

Roger Dooley: Great, well, I think watching that would be a good three minutes well spent for everybody in the audience, I hope you’re getting at least a little bit of royalty on every Apple Watch sold for that.

Nilofer Merchant: Wouldn’t that be great? You know, it’s funny, my son, this is what’s so cute is, he was … gosh, he was probably nine when I gave that talk and now he’s 14. I remember when the Apple Watch was announced, because he came up to me and he said, “Listen to this.” He played the quote coming out of Tim Cook’s mouth, and he said, “That is so amazing. You planted that idea out in the world.” It’s just such a beautiful thing to see ideas spread, I think that’s a big part of why a lot of us do the work we do, is not to get fame, because very few people actually trace it back to me. Certainly my son does, but other than that … but it’s just this idea that can go out in the world and hopefully positively benefit other people’s lives.

Roger Dooley: Right, and that’s really a pretty good lead-in to your book, I guess, but I have to ask you as a fellow speaker, do you agonize over the best word to refer to the part of the anatomy that we all sit on?

Nilofer Merchant: You know what was really funny? I’ll tell you a funny story is, I was planning on saying “bottom” and it just wouldn’t come out, and I was like, “What’s the … still a very PC, very appropriate, kid-friendly kind of word?” I could not find it. Then the day of, it just came out of my mouth as “tush” and as I patted, I’m giving something away, as I, in the talk I actually pat my bottom, and I basically give myself a little smack to point out this anatomical thing. Just to embody it. At the moment that I smacked my bottom, I looked down, like where your eye meets someone else’s eye, and I meet Bill Gates’ eyes. Sitting right next to him is Al Gore.

I had this super, like … if you now watch the video, you’ll see this look of horror go across my face, like, “I just smacked my ass in front of …” having this sort of like, oh my God, that didn’t just happen, moment, it was very, very weird. That’s the person who’s eyes you make contact with as you smack your bottom?

Roger Dooley: That’s a great story, Nilofer, but it makes it memorable, too, you know? If I asked somebody what they remember, first of all, it’s a very short talk, and very impactful, and I did not … to your knowledge is that the first sitting and smoking reference in the wild?

Nilofer Merchant: Yeah. I actually came up with that phrase to communicate it. And in fact, what was really funny, is after the talk went viral, some researcher, and I want to say he’s out of Cleveland Ohio, was like, “I once used that phrase before.” And I was like, “Okay, you can have it then.” I was just som amused at how upset he was that I had used the phrase, because if you had Googled it, you wouldn’t have found it anywhere.

I was trying to coin a term that would land it, right? What would be the huck point that would let you look at it in a fresh way? And I had been watching Mad Men, and thinking these people are smoking without intention. And I thought, that’s the common thread. What’s the thing we’re doing without any conscious thought?

Roger Dooley: Well, that’s great Nilofer. I’ve heard that phrase a million times now, in different context, and different variations, but that’s wonderful.

Speaking of words, I’m a big fan of authors creating a unique word for book titles, as you might guess, form my own. Now, I love onlyness, not just because it’s novel, and it’s a novel idea, but because it contrasts with the similar-sounding word, loneliness. Was there a Eureka moment when it came to you?

Nilofer Merchant: The Eureka moment was actually when I was working with an editor I really enjoy working with, over at Harvard, Sarah Green, and she and I were saying, there are so many of us in society that don’t get seen. We’re the only woman in a boardroom, so we get defined by that characteristic, rather than who we actually are, of if we’re the only person of color, or if you’re the only young person, or if you’re not the variety of ways in which a lot of us are seen as the “only”. And I said, “But, isn’t it true that, that onlyness that we each have, is exactly where value creation comes from?”

So, there’s this weird thing that happens, where we get negated for that very thing that actually is distinct to us. So, we were playing around with this word, and onlyness came out of this exchange. I said, “Isn’t that what we’re trying to capture, that value creation can now come from anyone, quite possibly everyone, based on that spot in the world only they stand?” So, it was really a collaboration with Sarah, and Sarah and I, to be fair, actually don’t like coining words, Roger. We are the kind that usually make fun of it, because typically it’s seen as a marketing ploy, and we were trying to say, “But this is something about the economic point of value creation, it’s no longer about organizations, but about the specific thing.” so that’s the origin of the word.

I didn’t want to use the word for a long time, because I think sometimes people think about it as me saying another version of me more of you, like branding. And I’m actually very much talking about, about it’s the first time in literally thousands of years, where people’s ability to create value based on that spot in the world, only they stand actually has the ability to work. You can now be in connection with other people, hence the ness part. You can be connectedness. So, different people born of different onlies, can actually join together, and formulate enough change in the world because of that common loosely connected, but commonly held set of principles that they care about.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, Nilofer, early in the book, you have a story from Autodesk, and it totally resonated with me, because really early in my career, when I was still a young and foolish, I guess, now I’m old and foolish, I was a project manager in a matrix organization, and I was responsible for getting these big industrial projects done on time, and under budget, but basically, I had no direct authority over anybody to get it done. So, the people in purchasing, and engineering, and so on had their own priorities, but were in total control of what happened on my projects, so I tried working with them nicely, and do the things you normally would try and do in a matrix organization, but basically that wasn’t happening because of their own problems, and situations.

So, I adopted the strategy of skewering them in meetings where top management was present. And that did not go over very well. But you’ve got your own sort of variation on that story. Why don’t you tell that?

Nilofer Merchant: Sure. It’s such an embarrassing story because up to that point, I hadn’t been in charge of something as big as what I was being asked to do at Autodesk. At the time, I was responsible for the revenues number, actually delivering on that number, across every region, for the North American division, which was at the time, about a $200 million division when I started, and $300 million when I ended.

Trying to figure out how do you get people to go along with an idea? How do you build on that? So, I did just as you suggested. I skewered someone publicly, because I was using essentially an old form of power, right? Which is, can I use my authority, and more importantly, someone else’s authority, to get you to do what I want you to do?

And the reason I shared the story, is because power had traditionally been about title, rank, and the ways in which I could get a more powerful person to tell you to follow my lead. Now, I’m actually pointing out, what if we could actually build more of a coalition of people who care about the same things? It allows you to actually navigate work, not by hierarchical structures, but by ideas. That’s why I shared that story, is this tilt that happened in my head, from that experience of power is, when it’s coercive, never actually creates change.

Roger Dooley: Oh, exactly. I know that in my case, in trying to invoke that power, to get done what I wanted done, it ended up being completely counter-productive, and got even less co-operation. I didn’t get fired, but I got chewed out by the big boss. So …

Nilofer Merchant: And I got fired, but one of the things I really want people to understand is, we don’t teach this well, about how to get people to do things by choice, because we think about power in a very particular way. We think about it as the way we get people to follow us, and it assumes passivity, or stupidity on their part, and active leadership on our part.

Actually, there’s a different form of followership, which is about assuming the other person actually has a brain, and wants to actually come at things by choice. So, that’s the actionable part of that story, which is, how do you start to hold an idea, not as if you’re holding it in a closed fist, and that pounding over the head of someone else, but opening up your palm, opening up that idea, so that someone else can come along and pick it up as their own?

That tectonic shift, because it’s really a mindset, but it’s also a set of practices we can do, to say, “How do I hold an idea in such a way that you can come co-own it with me?”

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So, a key concept that underlies a lot of the book, Nilofer, is that you don’t have to be a mover, and shaker, to make a difference. I think a lot of us see a problem, recognize that it’s a problem, it’s important, and then we shrug our shoulders and say, “Well yeah, but what can I do? I don’t have connections, or wealth, or a specialized knowledge. I’ve got a day job that I can’t really quit, and just sort of move on.”

You mentioned Bill Gates. We get how Bill Gates can take on a problem like malaria. World leaders will take his phone call at any time of the day. He’s got a big staff that works for him. He’s got the financial resources to fund stuff. How can regular people make a difference?

Nilofer Merchant: Yeah, so let’s just share one of the stories of the book, and pull it apart for a second together. One of the stories I love in the book was, a story of Franklin Leonard. He’s a young man when he shows up in Hollywood. In fact, the backstory is, he had been watching Netflix. After he lost his job at MacKenzie, he’s binge watching Netflix, and has this epiphany of, he’s always loved Hollywood, always loved storytelling. What if he just shows up in Hollywood, and see if he can land a job there?

So, he does that as a relative pee-on, and one of his jobs was schlepping, and getting coffee. One of this jobs was to read scripts, because it turns out that job of readings scripts, and first sorting them, is a job delegated to the most junior people.

After a year of doing this work, he realizes he’s seeing only really trite stories come across his desk, and he figures he must be really bad at his job. And what if he could ask for more help? So, he sends out an email to the 80 some people he has met in his first year, and he says, “I want to find scripts that you’ve loved, that have not been put into production, but that you’ve seen within the last year, and in return for you participating, and giving me your answer, I will roll up everyone’s answer into a master list, and share it back.”

He does this under an alias, because he doesn’t want people to know that basically, the things he bad at his job. He doesn’t want his boss to find out. And people do this. He uses his ex McKenzie skills, and does the tabulation of this stuff, prints off the top five scripts, and goes on vacation, only to return two weeks later … This is back when people did actually left town, and didn’t check their device all the time, which I really envy.

He comes back, and he see this thing that he’s created, called, the black list, circulated back to him hundreds of times. And he then continues doing it year after year, so the numbers of how many Oscars, how many scripts that were essentially in the dust bin, were then pulled out, and put into production, were astronomical. And the numbers in the book are … I could quote them, but I’ll just ask you to trust me. The data’s unbelievable.

But what was so fascinating to me, was Franklin didn’t have title power. He didn’t have money power. He didn’t have, in fact as an African American in Hollywood, he was definitely one of the people most likely to be unseen, and what he was trying to advocate for, were stories that were not already hyper-connected into the power network of Hollywood.

So, he’s young, he’s black, he’s inexperienced, so all the things that would suggest he’s powerless, and yet by asking a new question … So, here’s what he asked, which I should slow down on, he asked, “What do you love?” And he allowed a group of people to anonymously answer that question, so that it was safe for them, because Hollywood is run by politics, so that they could participate with him, and actually answer a question that they too believed was important, which is, “What are the scripts we absolutely love?”

Then they collectively then, were able to act on this. So, it’s not just Franklin’s action, it’s his ability to find the other people who care about the same things as he does, that forms this new lever, by which you can change the world.

So, onlyness is really, that why it embodies this idea. It’s, what is that thing that only you see at first, that then you join with other people, in connectedness, to then create that lever to dent the world? And it lets you bypass traditional power structures, and status that usually filters people out, rather than funneling in new ideas.

Roger Dooley: I think that’s a great example Nilofer, but now there are also plenty of examples of people who do not necessarily chuck their entire past life, and show up in Hollywood with nothing. I think that it’s possible to explore areas while you’re still doing something else, so you don’t have to dedicate your life to it, immediately, or at all, ever necessarily, right?

Nilofer Merchant: In fact, that’s exactly who I wrote … Thank you so much for pointing that out. One of the reason why this is not a book about entrepreneurship, right? This is not about go follow your dreams so you can go build a brand new thing. I was really pointing out, how could any of us, in whatever small … That’s why the word of the book, “dent” in the subhead, dent is there. Dent by dent, shape the world to be however you imagine it could, or should be.

So for example, one of the stories I shared was my husband had been thinking about how to do what he called, world changing things. So, he wanted to make a difference in the world, but he couldn’t imagine how to do that in his day job, in the same way. He wanted to quit his job to go do it. And it turns out he could actually do it on what became on hour a day. He formulated with other people, a website called, Appropedia, using the Wikipedia network model, but for appropriate solutions. So, if you wanted to build, let’s say, a water well in Kenya, you could use the most locally sourced resources, to do that. This site now has something like 20 million visitors a year, and something like 16,000 projects, and all based on people contributing an hour here, an hour there.

So the idea with onlyness is, what are the ways in which your purpose and passion can be manifested in the world? And it can be a small dent. It doesn’t have to be a huge one.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, that reminds me of an example of my own, Nilofer. And I didn’t think about it in these terms until I read your book, but I think it fits pretty well. Way back in ’96, and then again in 2001, I helped my two kids through the college admissions process, the whole researching and visiting, applying, getting financial aid, all of that stuff, and even though we were probably better equipped than most families to deal with that, it was still really frustrating, and there was such a tremendous lack of information out there.

The high school guidance counselors tried to help, but they really didn’t know very much, at least they couldn’t answer the questions that you wanted answers to. The books available were okay, but not sufficient by a long run. So, after that, started thinking, gee we certainly knew a lot more at the end of the process than we did at the beginning, and had we known everything we knew at the end, we probably would have done a few things differently.

Everything turned out fine, but you never know. Say, “Well, if we would have done this, would have done that, what else could have happened?” So, I ended up connecting with a friend who was a college admissions counselor, and started a little website called, College Confidential, that was really just intended to be a resource to help students and parents through what was a really confusing process at that time. Ultimately, it became the busiest site in the space, and-

Nilofer Merchant: Oh, fabulous. Beautiful, beautiful example, right?

Roger Dooley: Well-

Nilofer Merchant: It doesn’t have to be your main profession, but is a way to serve the world.

Roger Dooley: Well, yeah. And the best part was, this little crazy idea really ended up making a difference. So, just last week, I was in Chicago, and I gave a speech at the University of Chicago, and the host when he introduced me, asked, even though my talk was not about college admissions, it was about neuroscience and marketing, the host asked, “Who here used College Confidential as part of their College Search, and admissions process?” And just about every student in the audience raised their hand. And this is 17 years later, 10 years after we sold the business.

So, to your point Nilofer, I had no particular qualifications to attack this problem. I wasn’t a college expert. I didn’t have any powerful contacts, and with one kid just having finished college, and another starting out, I did not have much money to throw at it either, but started off as a side gig, both for me and my original partner, and it worked out.

Nilofer Merchant: Yeah, I think this is the real opportunity that we have now, that the network world that we lived in has really lowered the cost of us approaching ideas. And that’s one piece that I think has really changed. And what I think you’re also pointing to, is this notion about, it can be … Identity is a question we often don’t understand how it can relate to what we do. So, your identity as a parent, and someone who had just gone through this process, this particular experience, and then realizing actually a whole bunch of other people could possibly have that same need, allow you to claim this thing that as a parent, you can go, “What kind of innovation can come from me, as a parent?” But innovation comes from our own experiences, our own hopes and dreams, our own perspective.

And the problem is, that most innovation is denied, because we filter out those people who don’t fit the profile of who we expect an idea to come from. And so, the opportunity for each of us to raise our hand, and be able to say, “You know what? I see something. I’m going to go solve it.” Is this shift in how we have locus of control, or agency, using that neuroscience kind of language, right? What is it that gives us agency to be able to affect change in the world?

Right now, certainly the costs are lowered, and the sense of how we can conceive of ourselves has grown.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’m sure had I gone to VCs, and asked for funding, they would have laughed me out of the room, because we simply didn’t have all the ingredients that one would expect to have in that kind of venture, but we did have purpose, which seems to be something that’s pretty important among your examples, that having a purpose to one’s effort, makes up for deficiencies in the other areas.

Nilofer Merchant: Well, it becomes the connective glue, right? So, the reason why you and your colleague ended up forming together, was because you had a shared purpose in common. It wasn’t because of your age. It wasn’t because of your credentially. There was a series of things that we have typically sorted on, that would have said, “This person’s qualified.” And what actually made you qualified was your own purpose. It wasn’t because you had a degree in doing that before, or someone else had already given you that status. So, that’s the big shift, is how do we act on our purpose, so that in some ways, it’s the oldest idea ever, which is, how can what we distinctly bring to the world …

You know, the Bible talked about each of us having a light, but then how do we manifest it in the world? And now, I think we have this really distinct opportunity to have a bunch of really distinct perspectives join together, for both good and bad. To be fair, the same thing that’s driving me too, and the initiatives are there, are the same things that are driving white nationalists to now be far more organized than they’ve been in the last 20 or 30 years.

Roger Dooley: I guess there’s a good and bad side to everything. Nilofer, how could a person who’s perhaps listening to this, find their onlyness, and should they even look for it, or are there only under some conditions that one should try and find it?

Nilofer Merchant: No, so you know, it’s a funny thing. The way I characterize it is this, is what is that thing that is your history and experience, as well as your visions and hopes?

This morning, in fact, I was meeting with somebody who used to be a general council over at Google. And she is this super accomplished lawyer, has four degrees from Sanford University, is a Latina, and so on, and now a venture capitalist. And she was saying her life can be fragmented, meaning, sometimes she’s in a room where she’s advocating for Latina issues. Sometimes she’s in a room advocating for the best ideas to be funded, and so on. And she says she can’t really figure out a way to hold all of her.

I said, “Oh, let’s work on that for a minute. What is this spot in the world only you stand in? What is set of ideas you pursue?” It came down to her, very specifically about, can she create more opportunities for people? She pointed out that as a Latina woman, 50 years ago, her only set of choices in life, would have been to clean someone’s house, or care for someone’s child. And she was pointing out that actually her ability to get all of these degrees, and contribute to Stanford’s board, and so on, was directly tied to the set of opportunities she’s had since then.

Now, she specifically figured out, how can she invest in things that creates more opportunities in the world? So, here we are, what’s her history and experience, as well as her visions and hopes, in one sentence, right? She was just … as soon as she said it out loud.

I said, “Now, if you use that as a through line for what you care about, who else … what rooms can you put yourself in, where they care about the same things, not because of the fragments of you, you know, Latina, well-educated, yada, yada, but this combined sense of who you are, your onlyness, that your own personal onlyness that lets you then identify with other people who care about the same thing.”

So, it would put her in rooms of people who care about levers that create more social structures, more social scaffolding, that would change society. That became really clear in just a few minutes.

So, what is … as you draw your own stories … and it can be an evolving set of stories. What is it I so care about, based on my history, and experience, visions and hopes, that could then unite me with other people? And I’m not convinced it’s one sentence, and I’m not convinced it’s even one thing, because as we grow and evolve, we can continue to advance the idea.

Mine happens to be from innovation perspective. I’ve been in rooms for over 25 years, where I just notice companies, and organizations, and in fact society really damage themselves, by not noticing all the ideas at the table. And they basically pre-screen out, based on whatever room they’re in.

Sometimes, only the CEO’s ideas count. Sometimes only the engineering team’s count. Sometimes it’s only … You know. Go on … So, whatever room I’m in, I notice that there’s always a group of people being filtered out.

So for me, my biggest passion is, I believe it will serve society, by unlocking this capacity of all ideas getting account. And I point back to my early experience at Appl Computer, when I was an admin. One of the first meetings I ever got a chance to go to, and people said, “We’re going to brainstorm about x. Everyone should come.” And I took them seriously. I didn’t know any better back then. So, I prepared, and I didn’t the research, and I showed up. And what I realized was, in that room, because I was an admin, and not an MBA type, my ideas didn’t get to count. So, my history and experience, as well as my visions and hopes, are deeply tied to if we could get more of our ideas to count, we would open up that innovation capacity, and a set of potential solutions that humanity most needs.

So, that turns out to be my onlyness. So, if I say with you, Roger, for even two minutes, we could do it together with you. It’s just being clear about why do I care about what I care about? Not by the fragments of who I am, but the whole view of who I am.

Roger Dooley: You’ve got quite a few stories in the book, Nilofer. Are there some commonalities among the people that you spotted as you were collecting all of these. Are there a few characteristics that enabled them to succeed?

Nilofer Merchant: That’s a really good question. Well, background on why I chose the people I chose, what I was trying to figure out, for about 20 some years I’ve been trying to figure out how to get people inside organizations to look at all ideas. And I’m steadily frustrated by the fact that most organizations don’t want to change. They want to talk about change, but they don’t want to change.

I thought, what if I could actually study those untraditional players, who were using a different way of getting their ideas through, meaning using networks, instead of hierarchies. If I could just study what they were doing right, could I end up offering a solution for how we might work in the future?

So, I thought it would take me maybe 30 stories, to find 20 to write about, or maybe 40, to write 20. And it took me actually 300.

Roger Dooley: Wow.

Nilofer Merchant: And it took me much longer to do the research, because it turns out almost all the pioneers of people who are actually affecting change using networked models, aren’t actually really clear about what they’re doing right.

In fact, going back to the story of Franklin Leonard, when I asked him what did he believe he did right, or different that succeeded, he said, “Oh, I shone a bigger light on scripts that were bring unseen.”

I said, “Actually, if that were true, you could find a bigger light, so that’s not actually what you did.” And it was one of those awkward moments, where I’m like, “Yeah, that’s not it, but I don’t know what it is yet.” And it took me another five stories of studying other examples, to go, “Ah, what he actually did, was create a safe enough framework, for people to be able to gather together, around an idea, and he basically changed the very framework, so that, that actual embedded notion that a lot of people in Hollywood actually value, could come through.” And it was the safety of that anonymity in that case, that actually let people be able to have their ideas be seen.

So, for each of those examples, I think the common thread then, was they were all willing to chase an idea, even and in spite of the fact that no one else believed it was possible.

And in fact, at some point, I had turned to … You’re going to like this neuroscience reference. I had turned to Herminia Ibarra, who’s an expert on identity, and teaches at London Business School now. At the time, she was at NCEd. I said, “Listen, I’ve done 150 interviews, and all these people are having the same profile, in terms of how they’re relaying the information to me. If I am seeing them at … Let’s put this on a scale. I’m seeing them, if the scale was one to ten, ten being a finished accomplishment, I’m talking to them at ten, and I’m asking them to tell me where they began. They would start, what felt to me, like a three or four, because as I backed them up, and backed them up into their story, they were not telling me the first two, or three years of their experience.”

And I was telling Herminia this story, that all of the stories are showing up with this sort of camouflaging of the first, early, formative years. And she said, actually, this makes complete sense, when you understand identity. And the analogy she had used, the metaphor she had used was, it’s like the building of a house. So, as we’re building out a new part of ourselves, for something we care about, we first have to put up the 2 x 4s, and then later the drywall, and then later the paint, and then later the furnishings. And we don’t even know what that room 100% looks like. We don’t know if we’re aiming for a bathroom, or a kitchen, or a living room, until the shape of it starts to happen.

So, what people are doing in their formative stages of trying out new things, and trying to go affect change, they’re not telling you that early stage, because even to themselves, they haven’t acknowledged that they’re actually working on it. It’s just in development. It’s in this almost background phase, where they’re testing out their ideas, testing out what it might look like. So, you can’t explain it to anyone for a long period of time.

And yet, each of them gave themselves permission essentially, to keep chasing this nugget, this little thing. Franklin sending this email at 9:00 pm at night, thinking, could anyone else care about this same thing? They gave themselves permission and absence of any knowledge that they were even aiming at a particular outcome.

Roger Dooley: And to continue to analogy, once that room is finished, you can’t really see the 2 x 4s underneath it anyway.

Nilofer Merchant: Beautiful.

Roger Dooley: You know, and I can tell-

Nilofer Merchant: Beautiful, and I think that’s the piece that we don’t know how to share with one another. So, almost every magazine article you see, starts with the, “And then I had an epiphany.” And the funny part is, we actually don’t have an epiphany first. What we do, is we have these nudges, and urgings, and clues. And if we don’t understand-

Roger Dooley: Two things that were there, come together in one moment.

Nilofer Merchant: Yes, exactly. So, I think we have to give ourselves more room to navigate those early, and exploratory spaces, to actually decide if it’s a 2 x 4, and decide if there’s drywall, and decide then next thing, and to honor that building process of new work that we’re doing.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we’re just about out of time, Nilofer. Let me remind our listeners, that we are speaking with Nilofer Merchant, author of, “The Power of Onlyness: Make Your Wild Ideas Mighty Enough to Dent the World”

Nilofer, where can people find you, and your ideas online?

Nilofer Merchant: I regularly blog at Nilofer Merchant.com. So, even though I get published everywhere, I always bring that back to home base. So, it’s N-I-L-O-F-E-R-M-E-R-C-H-A-N-T.com.

Roger Dooley: Great, well we will link there, and to any other resources we talked about on the show, on the show notes page, at rogerdooley.com/podcasts, and there will be a text version of our conversation there too.

Nilofer, thanks so much for being on the show. I hope we meet again soon.

Nilofer Merchant: Thanks Roger.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion, and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us, at rogerdooley.com.