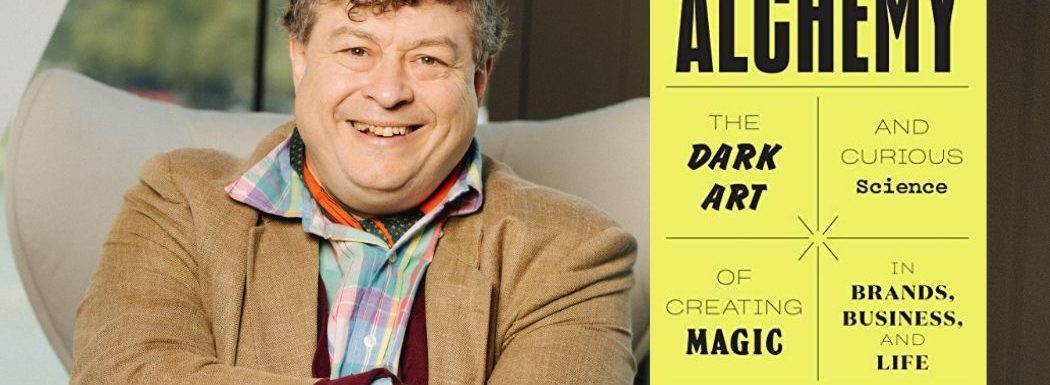

Rory Sutherland is one of the most influential advertising professionals in the world today. Having worked as the Vice Chairman of Ogilvy since 1988, Rory has formed a behavioral science practice within the agency, where his team works to uncover the hidden business and social possibilities that emerge when you apply creative minds to the latest thinking in psychology and behavioral science.

In this episode, Rory shares insight from his book, Alchemy: The Dark Art and Curious Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business, and Life, and breaks down why we do the things we do. Listen in as he explains how to increase the perceived value of an offer, what you must never do in customer service, and more.

Learn about the hidden business and social possibilities that emerge when you apply creative minds to the latest thinking in psychology and behavioral science with @rorysutherland, author of ALCHEMY. #branding #advertising… Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The importance of putting a time constraint on an offer.

- What EAST is and how to use it in your marketing technique.

- Why people frequently choose a site they have used before, rather than try a new one.

- Why toothpaste has stripes.

- Interesting studies that show the reasoning behind why we do the things we do.

Key Resources for Rory Sutherland:

- Connect with Rory Sutherland: Website | Twitter | LinkedIn

- Amazon: Alchemy: The Dark Art and Curious Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business, and Life

- Kindle: Alchemy

- Audible: Alchemy

- Robert Cialdini

- The Case Against Reality by Donald Hoffman

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr. Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m your host, Roger Dooley, and I’m really excited about today’s guest.

Rory Sutherland is the Vice-chairman of Ogilvy, the advertising giant that now styles itself as an integrated creative network. He’s worked there since 1988. If you wonder what a vice-chairman does, Rory has used that somewhat vague title to form a behavior science practice within the agency. This group strives to uncover hidden business and social possibilities by applying the latest thinking in psychology and behavioral science. He’s also the author of the book Alchemy, The Surprising Power Of Ideas That Don’t Make Sense. It’s a funny and informative book that examines questions like, why do we prefer toothpaste with stripes and drink Red Bull, even though it tastes horrible? My one phrase review would be that Alchemy picks up where Danny Ariely’s, Predictably Irrational, left off. Rory, welcome to the show.

Rory Sutherland: It’s a pleasure to be here. Thank you very much.

Roger Dooley: So Rory, from what I can tell, you joined Ogilvy right out of university. Is that right, and if so, how did you career evolve?

Rory Sutherland: It’s been like you. I started in direct marketing. So my first job, which was as a graduate recruit was at Ogilvy & Mather Direct, as it was then called. Later to be called Ogilvy One. I suppose, like David Ogilvy, I’d say my first love and secret weapon was, and still is to some extent, direct marketing. And of course, direct marketing, although it was back then, the less fashionable cousin of advertising, had some fairly significant advantages, which was it was immediate measurable. So whether you were using direct mail or telephone marketing or later on obviously, digital forms of communication, you had some form of measurement, immediate measurement. People responded if you did an off the press ad, you counted the number of coupons and you saw where they came from, which created incentives in credit to direct marketing by the way.

Rory Sutherland: It invested the split test, something like 25 year before medicine did. And basically medicine had ethical objections to the whole business of doing the randomized control trial. But early direct marketers, in the 1890s and 1880s were using split testing of creative and media as long ago as that. Now, in the case of medicine, with a few notable exceptions, I think there was the famous test about scurvy, which was probably in the early 19th century. Medicine didn’t get into the randomized control trial until quite a few decades later. 1940s, 50s, really.

Rory Sutherland: What was interesting about that is you quite often got results, which if you had been a conventionally trained economist, would have caused you to question your sanity. As a result, it was a very, very good social science experiment, I suppose. It was a very well-funded social science experiment in terms of what worked. What motivated people, what affected their decision making and what didn’t.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well you know where it’s funny. Your story about the appeal of direct marketing sounds like it came out of the intros to one of my talks. I don’t always do it, but sometimes I explain my background. When I got into direct marketing, it was paper catalog marketing, and I explained to people that at the time, that was the most scientific kind of marketing available, because we actually did some crude A, B testing with different cover designs, and over wraps and such. We did a lot of mailing list testing, of course to see which one’s might respond the most. We actually had a pretty good idea of what would work. Even using things like square inch analysis to look at the content and the products in the catalogs. We had a pretty good idea of what was working.

Roger Dooley: Now, of course, in the digital world, it’s like you’ve got an incredible amount of information. Too much information perhaps. But, at the time, it felt revolutionary to know what advertising was working.

Rory Sutherland: The one great lesson really was that it quite often paid to test things, which were counter intuitive, or not conventionally logical. I’ll give you a very, very simple example, which you will know. I will know. Everybody knows. I don’t want to turn this into a direct marketing 1918 marketing love in where we start talking about the jobs box, if you remember what that was. That was a highly decorative headline at the top of a letter surrounded by asterisks, which came from the days when, of course, you had to make a letter look like a letter, and therefore it had to be in typewriter typeface.

Rory Sutherland: But the interesting thing is that a very simple thing you’d find is that your response rate would be markedly higher if you wrote to people and made them an offer, and said, “You must reply before… Within the next 14 days,” Or “You must… ” more sophisticated too, “You must reply by before September the 15th.” In all truth, if you’d replied on September the 19th, they still would have sold you the product. But placing some sort of time constraint, some sort of scarcity on the offer effectively increased it’s perceived value.

Rory Sutherland: That was the kind of thing where to a conventional economist, you’d go, “Well, this is crazy, if you think about it.” Either the people want the product or not. It either enhances their utility to an extent to justify the price, or it doesn’t. Why on earth would putting a time close on an offer actually increase response? What testing showed was it did, and significantly so. So you’re continually coming up against these things and I even in the early days, the late 80s early 90s, I kept saying, “Look, there’s a whole science here which doesn’t have a name.

Rory Sutherland: It was only about 15 years later I discovered that the name was behavioral economics. I suppose if I’d buggered off at that stage, maybe I could have won a Nobel Prize or something. I was absolutely convinced that there was this whole area of study which required much greater codification. And much greater understanding, because the effect it would have on the response to something, in many cases things which were entirely what you might say tangential to what the product was, what it did, and how much it cost. For example, using little techniques like for the price of a cup of coffee a day. Well again, in conventional economics that was framing, call it price anchoring, or whatever you-

Roger Dooley: Believe it or not Rory, in this morning’s email, I had that exact subject line in an email. For the price of a cup of coffee, you can subscribe to our service.

Rory Sutherland: Actually of course, the way of the thing is, it worked years later on my own dad. My dad wouldn’t get, think of it as Direct TV to American business, Sky TV. And bare in mind, if you think about it, if you’d grown up in the UK you paid a TV license, and TV was either free to air, as in the U.S. funding by advertising, or it was funded by the license which you paid to the government, which was mandatory. So paying another 17 pounds, 20 pounds a month for further television was something where if you’d been born in 1930, it was not a natural thing to do. And my father refused to do it.

Rory Sutherland: I said, “Look, you’d really enjoy these extra channels. The discovery channel, the history channel, and so forth. Genuinely, I really recommend it. In fact, I’m willing to pay for you to have it.” Even when I offered to pay for it for him, he wasn’t interested. Then finally I said, “Hold on a second. Don’t think of it as 17 pounds a month. Think of it as 70 pence a day. That is as in being blunt about it, you pay 2 pounds a day for your newspapers.” He gets The Telegraph and The Times in paper form. So I said, “If you’re paying 2 pounds a day for newspapers, paying 70 pence for another 150 TV channels doesn’t seem all that crazy, does it?” Suddenly he completely changed. He said, “No. I suppose you’re right.” And weirdly he went and he subscribed with his own money, and he’s not become something of an advocate.

Rory Sutherland: Undoubtedly, those things were I think, certain product to have been doomed or have been successful. Not because of what they are intrinsically, but because of the way in which they’ve been presented, and the way in which pricing has been presented. I think it’s undoubtedly true.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well sure. Look at travel ads these days. If you go to sites like hotels.com, or booking.com, or any of those. And all of the little psychological cues they use that this hotel has been booked 37 times in the last 24 hours. There’s 12 people looking at it right now. We only have one room left at this price. I mean, all of these cues, the scarcity cues, and urgency cues. But this is really an extension of what you’re talking about was being done back 30 plus years ago. In the catalog business we did something similar. We would put a little over wrap on that said, “this may be your last catalog.” And routinely, if you didn’t over use it, routinely that would give us probably a 15 to 25% boost in sales. Just that little extra piece of paper on the outside of the catalog saying that you might get any more of these catalogs. Nothing is totally new, but of course today the tools are so much more sophisticated.

Rory Sutherland: Well my dad was in the property industry, and he always said a very famous phrase which is, “No one would ever buy a house were it not for the fear that someone else might buy it.” I always wondered, when the state agents have these open house days, where 15 people go and shifty around the house. I’ve always wondered what percentage of the value of those open house days are the fact that if you have an open house day on the calendar in two weeks’ time, you can say to a perspective buyer, “Of course, we’re holding an open house day for this house in two weeks’ time.” And the perspective buyer, who at that stage has been demurring, suddenly goes, “Oh cracky, they’ll be 15 people looking round. Oh of them is sure to want to pay asking price. I’d better go in with an offer pretty fast.” I don’t know.

Rory Sutherland: And the person at of course very creditably, in what you might call face to face salesmanship rather than direct marketing. And I think he’s, in many ways, the father of modern behavioral economics, as Robert Cialdini. I mean, the father of behavioral economics is Adam Smith, by the way. Because I mean, his first book, and actually his entire approach to life, is that of a proper social scientist, not a pure mathematical economist.

Roger Dooley: Before economics became all about the math.

Rory Sutherland: Before it became obsessed with essentially ignoring those parts of reality, which weren’t easily quantified. Economics was behavioral economics, Cialdini said. Austrian school economics is also behavioral economics. They had a discipline called praxeology, which is the study of human decision making and action. The Austrian definition of economics was the study of praxeology under conditions of scarcity. I’m very sympathetic to the Austrian view. The idea that value is subjective and it’s constructed in the mind. It’s not something that’s constructed purely in the factory. Their approach to praxeology and books like Mises on Human Action, were really behavioral economics text books. And it still annoys Richard Thaler that he still gets people coming to him after lectures who basically go, “Look, all this stuff is in Ludwig Von Mises. Why are you claiming it’s new?”

Roger Dooley: I think the other thing that frustrates Thaler is that he’s got a very simple prescription that when he’s called in often to consult for governments or big companies, explains that if they want people to do something, make it easy. I can sense the frustration in both corresponding and in his public writing that it’s not that difficult. Just make it easy and people are going to do it. But they ignore that advice and are looking for some magic behavioral button to push, instead of just making it easy.

Rory Sutherland: The Insights Team is part of the UK government. Their prime methodology is called EAST, and it’s easy, attractive, social and timely. Now I was… By the way, I want to be clear about this. I tend to look at these things by always reversing them. Not difficult. Not unattractive. Not weird feeling. And not poorly timed, or not inappropriately timed. Because in a sense, it’s the failure, it’s difficulty… If you look at it, removing difficulty is probably a more important function of the marketer. Removing negatives is a more valuable use of a marketer’s time than actually adding positives. Because, I think, we’ve been polluted by this economic idea about it’s all about communicating added utility. Marketers tend to focus on the positives. Actually, it’s the removal of a negative which is probably more decisive.

Rory Sutherland: I mean, it’s very interesting if you look at it. We’ve just switched from Zoom to Skype on this call. Now Zoom did one brilliant, brilliant thing, which is it gave your meeting a URL. We all understand what URL is. It’s a unique resource locator. If you click on a URL, it takes you to that particular place, which could be a webpage. It could be a music file. It could be anything. Now by giving the meeting, a prebook meeting, its own URL, you essentially made joining that meeting an order of magnitude less frustrating, then starting our Skype meeting was, where you had to share your particular name. You then had to friend me. One of us had to ring the other. The other person had to be present in order for you to join the meeting. If you think about it in those terms, Zoom… If you look at Zoom, it’s a fascinating success story because you’re up against Google. You’re up against Apple. You’re up against Facebook. You’re up against Microsoft. And yet, you’re winning. Right?

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). That’s so true. I mean, another fellow you’re probably familiar with is B. J. Fogg at Stanford who has his Fogg behavior model and he says, “Don’t focus on motivation, focus on making things easier.” Those are the two drivers in his model. The other one is the prompt or trigger to get it moving. But you can either motivate or you can work the ability dimension which is basically lack of difficulty or lack of effort.

Rory Sutherland: And actually it worries me, because it strikes me that quite a few digital entities enjoy an unfair competitor advantage simply through habit. So that the experience of buying something on Amazon, because you’ve done it 297 times before, is always going to be extraordinarily lower in terms of the EAST model, if you think about it, than in all actually, probably certainly in the first three of those criteria, is always going to be extraordinarily much easier than suddenly navigating some new site, having to have the fear of putting your credit card details into yet another box.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). For sure.

Rory Sutherland: And so one of the things we have to do is we have to discuss where behavioral science can identify cases where competition is not being well served, not for economic reasons. The standard reasons which economists always advance, which are blah, blah, blah, economies of scale, market dominance, et cetera, which are undoubtedly in some cases true. But there are also psychological cases where, I think, market power can be very, very easily abused.

Rory Sutherland: I mean, an interesting one to me, and I’ve been talking to someone… And this fascinates me as a question. I’ve always had this niggling doubt in my mind. It’s about 25% of my brain that thinks that Amazon as a business is overrated. I’m never quite sure, because Amazon is patently very successful, although not as successful as it’s stock market price. Perhaps a chance if we’re being glib about it. But a friend of mine who used to work for Ogilvy called Nick Brackenbury, works for a company, founded a company called Near Street, which makes store inventory as searchable as online inventory is. Here’s my question. If you search anywhere online, and you may well, by the way, use Amazon as your search engine to begin with, but even if you search on Google for a particular item.

Rory Sutherland: I was buying a front panel for a name speaker the other day. If you search for it online, all of the available examples of that item will be those that are on sale from online retailers. So therefore, you might choose the lowest priced one. You may choose your favorite retail brand. You may choose a company that’s reliable at delivery. But you’ll almost certainly go on to buy it online. What happens when you search, and it also says, “We’ve got one in the local shop for the same price, which is three miles away, and you can reserve it.” Do we really want as much stuff to be delivered to our homes as Amazon’s growth suggests, or is that simply a product of the choice architecture and the past dependency of ordering, which is by the time we found the damn thing, the only thing we found is the online retailer’s stock of the thing.

Rory Sutherland: And if you actually change the choice architecture where you go, “Where are these things available both online and off?” We’re actually, a large number of people, particularly in the UK, which remember is a tiny country. There is a reason why a significant number of people in the U.S. would want that thing delivered, which is that their nearest specialty hi-fi store is 140 miles away.

Roger Dooley: Even on a somewhat closer scale, I’m in Texas, which is a very large state, and things are just more spread out. If you live in a suburban location, which I do, the closer specialty retailers are going to be at least 10 minute drive and quite possibly a 25 minute drive depending on what you want. Maybe even 30 plus, if it’s something that there’s only one location in the overall city. Yeah. Compared to that, having it show up on your doorstep in 48 hours is pretty darn convenient.

Rory Sutherland: Other hand, A, Texas is the world capital of parking. So wherever your specialty… I know. I’ve been to Texas quite a few times. Absolutely love the place. And one of the things you can constantly say about Texas is, where there’s a shop, there a car parked.

Roger Dooley: Yes. And the spaces are even generous because everybody in Texas drives these massive pickup trucks. Even the parking spots themselves are Texas sized.

Rory Sutherland: My brother remembers there used to be compact bays. And he said, “Back home in England, I could park my Jag in a compact bay, is how vast things are.” But actually, if you think about it, in the next three days, you’re probably going to be going to one of those shopping malls, or strip malls, or you’ll be passing by it. If you could wander in confidently and say, “I reserved this speaker grill.” The other thing you’re doing there is you’re establishing a little bit of social contact with a hi-fi store. We’re a social species remember. You may wonder into the store and discover a few other things you would buy. If all you want to do in the next five days is buy a speaker, and you’re not intending to leave the house for any other reason, then delivery wins. But most of us on most days leave the house and we go to a place of greater population density than the place we live, and in going there either to go to work or shopping or whatever. And in going there we pass a variety of shops and car parks and so on.

Roger Dooley: Plus, there’s the instant gratification if you happen to be… If it’s Saturday and you want to be working on your stereo system that day, not the following week, then hey just jumping into the car and going to the store and getting the pieces that you need is more convenient.

Roger Dooley: Hey Rory, I want to get on to some of the ideas in the book. Alchemy is such a great book. I found it really entertaining and informative too.

Rory Sutherland: This may seem like a massive distraction, what I was just saying about is Amazon in the future? The reason I’m asking the question is I think it’s the fundamental question which behavioral economics asks, which is are people doing what they do for what you might say the standard issue reason? The standard issue reason would be they’re buying from Amazon because it’s cheap. They’re buying from Amazon because it offers wide choice. They’re buying from Amazon because it’s convenient. Those are the standard issue reasons. And all of those things may be, by the way, partly true. But there’s always a behavioral dimension, which is are they also just buying from Amazon because the choice architecture of online search forces them to do it? For example, my guess would be now if you tried to sell your house without listing it online, you’d have a bloody long wait.

Roger Dooley: Quite true, quite true.

Rory Sutherland: People may be buying your house when you sell your house. They may well be going to a conventional realtor, or state agent, as we call it in the UK. But nonetheless, if the thing can’t even be found online, then as far as your brain is concerned, it doesn’t even exist. So by rebalancing things so that physical retail inventory appears online alongside online inventory, we’ll start to see what the true figure is in terms of preference for delivery over collection. So I think this is the vital thing. I think that there’s a wonderful J.P. Morgan quote that I use in my book which is, “Every man has two reasons for doing what he does. A good reason and the real reason.” There’s always an official economic reason, which is a back filled, post rationalization.

Rory Sutherland: We clean our teeth to prevent dental decay. What behavioral scientists has to do is to say one, we don’t really know why we do what we do, because we don’t have introspective access into all parts of our motivation. My friend Robert Trivers, the evolutional biologist argues, as does Don Hoffman by the way. New book. I’m going to give a good book plug here which is, The Case Against Reality, by Don Hoffman. He claims as a psychologist that what evolution has given us is a sensory apparatus, is really like it’s actually a representation of reality, which is usable and advantageous and even uses that term, is not remotely accurate. He says its as much linked to the reality of what’s going on as a desktop on a computer is linked to the reality of the electronics going on beneath.

Rory Sutherland: So if, as I believe, that we don’t perceive the world remotely objectively and many of our motivations may actually be inaccessible to conscious introspection. A large part of why we clean our teeth I would argue is actually fear of bad breath and vanity, in the sense that would you clean your teeth after a meal at lunchtime when you’re out at a restaurant? Almost certainly not. Would you clean your teeth before a date, or first thing in the morning before you go to work? Almost certainly yes. Further bit of evidence. 95% of the world’s toothpaste seems to be flavored with mint, which doesn’t make sense from a dental health perspective, but makes a hell of a lot of sense from a bad breath perspective.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So that leads you to the question about toothpaste stripes, which we teased already, so we have to deliver on that promise.

Rory Sutherland: Oh no. So the stripes in toothpaste when you think about it, they make us feel the product is more efficacious because patently something… It’s a more credibly claim. If you’re claiming that it freshens breath, that it removes plaque, and it reduces cavities. Having three visibly separate components of the product, increases the plausibility of that claim. But of course the stripes cannot, by definition, add anything to the efficacy. Why you bother to keep them separate in the tube, when the second you put the stuff in your mouth you’re mixing it all up.

Rory Sutherland: Conceivably a toothpaste where you have to use the green tube first and then the blue tube, there might be some value to having two separate ingredients used in a different order. But by definition the stripy toothpaste can only be a psychological aim to our belief in efficacy. It can’t actually add to the efficacy itself. Strangely, nobody’s really asked this question. We often ask the question, how do they keep the stripes separate in the tube? But we haven’t asked the secondary question, which is why. I think the reason for that is what I say is alchemy.

Rory Sutherland: Apparently washing powder, by the way, is more effective perceptually if it has little colored flecks in it. We’ll automatically see that as more efficacious washing powder, than one that’s homogenous and just all white. Now, when you say, “Yes, but hold on. How does that affect reality?” Well in the case of reality it doesn’t. But actually, you will perceive your clothes to be cleaner if you’ve washed them in a powder that uses mental mind tricks. In the same way rather tragically, by the way, that if your washing powder says it’s kind to the environment, you will see your clothing as being less clean than if that claim were not made on the packaging. Our brain tends to perform a trade-off, which is well if it’s kind the environment it’s going to be a little less efficacious. And it actually perceives that lack of efficacy in the finished product, even though objectively it isn’t there.

Rory Sutherland: The example I always give, partly for joke value, but because it’s a recognizable truth is that your car drives a lot better when you’ve had it cleaned. If you have your car valeted or you take it to a really good carwash, when you drive your car away with that dripping slightly onto the hot tarmac, not only is your car cleaner, it also drives better. It’s quieter. It’s more comfortable. It feels better in lots, and lots of dimensions. Now there was an engineer friend of mine who is driven insane by this and was convinced that actually the act of cleaning the car torqued the body panels or reduced vibration. He was an engineer. So he had to believe there was an engineering explanation. There wasn’t. It’s entirely in the head that shinny cars just drive a lot better, and feel better to drive, than dirty cars. Once you accept that level of blurriness in human perception, in a sense marketing goes from being an optional extra, to a little bit of a necessity.

Roger Dooley: It becomes part of the product experience itself.

Rory Sutherland: It actually is then, just as they always said about lager particularly. Less so about conventional hoppy beers. But most people couldn’t tell the difference between lagers in blind tastings. The argument was you are drinking the advertising. The very nature of how the product’s advertised and what it’s advertised as will affect the taste and enjoyment and refreshment you derive from drinking it. Sorry guys, but you just got to accept that. And if you want to read my book, which is marketer’s take, Don Hoffman’s book is a scientist’s take. If you like, Robert Triver’s book is very much an evolutionary psychologist’s take. But we’re all essentially saying the same thing. Look guys, if you don’t design for perception, if you’re designing a product, or promoting a product entirely around its objective qualities, those things which happen to be measurable, you’re in danger of taking a hugely wrong turn. The example I give is a fantastic bit of psychological engineering is Uber, which of course doesn’t necessarily reduce the weight for your car. It massively reduces the level of uncertainty around the weight.

Roger Dooley: I was just on a podcast myself the other day, and it was a podcast aimed at contractors, people who come in and fix things in your house. And I used that exact example. I was saying, “Well, how can we do things better, get more satisfied customers?” One of the huge complaints in the U.S., perhaps in the UK as well, is that contractors don’t show up when they’re supposed to. The set the time. They’ll be there Tuesday at 8:00, and of course 8:00 rolls around… Or they say Tuesday between 8:00 and 11:00 and you are frozen in place. You can’t move. Where if they simply provided you with information as to their arrival time… If they’re going to be late, they informed you.

Roger Dooley: Or I just had somebody come out and do a little voltage work and they actually did an Uber-like thing where you could see where you’re service person was on a map, when it got close. Not all day. You couldn’t track them the whole day, but once your appointment was imminent, you could see where he was. That made the experience so much better than just sitting around, “Where is that guy? Is he going to come? Did they forget about me? What’s going on?”

Rory Sutherland: Interestingly, it’s fascinating you mention this because I’ve long been intending to go to companies like Task Rabbit. There’s another company in the UK, which is actually owned by Centrica, which is called Trusted Traders. There’s a whole bunch of these websites, which enable you to find handymen and people who can perform work in your house. And one of my contentions, by the way, is that someone needs to reverse the normal discotic. The first question is, what do I need doing?

Rory Sutherland: Now the actual truth of the matter is I’ve got seven things that need doing at any time. I’ve got a TV that needs mounting to the wall. I got a washbasin that needs replacing. I’ve got a waste disposal unit blocked. The question I really want the answer to first is, who’s free on Friday? Because I work from home on Friday. Basically it doesn’t really matter what time they turn up on Friday. I can cope with that. Thursday, I’ve got a lot of meetings at work, totally different matter. They turn up a half hour late, the whole thing’s a catastrophe.

Rory Sutherland: Now interestingly, I think you’re completely right there. The uberfication of what you might call the home handiwork industry. It fascinates me because I’ve got this broken washbasin. As I argue though, the reason I haven’t repaired the washbasin in six months is not economic. If there were a contactless payment device above my washbasin, where I could wave a credit card and pay 300 pounds and have it replaced, I would have done that within 10 seconds of the washbasin cracking.

Rory Sutherland: The entire reason… I would say there is a lost economy of in the U.S. it’s probably 50 billion a year, which is created by people failing to get home tasks done, whether it’s decluttering, whether it’s putting up shelves, whether it’s repairing plumbing, whether it’s hanging televisions. There’s a lost economy there which runs into tens of billions, probably in the UK it runs into billions, which is entirely resultant not of cost or time or expense. It’s entirely the result of coordination problems and uncertainty. And if you can solve that problem, and you can use technology to solve that problem, which is what can I get done on next Friday. If you have an answer to that question, and I don’t care whether it’s my waste disposal unit, whether it’s my wash basin. Somebody can come in on Friday and sort some shit out, I’m there.

Rory Sutherland: If you rearranged, as I said, the way in which we’re selecting the thing, but not problem specific, but who’s free on Wednesday, and then I’d have a whole bunch of jobs that I might be able to get done. I wouldn’t be surprised, by the way, if the guy who replaced the wash basin could also fix the waste disposal unit. Once you can create something like that, my view is you’re freeing up billions, and billions of dollars of totally squandered economic opportunity. In the same way that until Uber came along.

Rory Sutherland: Then let’s look at the wastage for Uber. You didn’t ring for a car not because the car was expensive, but because you couldn’t stand the uncertainty of arrival. Secondly of course, when the car arrived you didn’t come out of the house all that promptly, and you left the poor guy waiting for 10 minutes. Two reasons. One, you could claim you didn’t know he’d arrived, so you had plausibility, and two, there wasn’t a passenger rating system. So several of those things. First of all with Uber, I don’t mind really waiting 20 minutes because I know when the guy’s going to turn up, and I can moderate my behavior accordingly.

Rory Sutherland: So if it’s going to be 20 minutes, I’ll have a cup of tea. This is British solution, not a tech solution. 20 minutes to wait in the UK it’s an automatic solution, you make a cup of tea, essentially. Maybe I get on with a few emails, then I make a cup of tea. It doesn’t matter. 20 minutes. I know what I can do. If I don’t know whether it’s to be five minutes or 25, I’m in a complete funk. I don’t know what to do.

Rory Sutherland: Second thing is of course, it means that I’m desperately worried about dropping below a 4.8, so when the car does arrive, and because I can see the car has arrived, I’ll basically evacuate the house within about two minutes. So the amount of time wasted by cars sitting on the road waiting for people to come out of a house is also reduced. So, it’s really, really interesting to look at this.

Rory Sutherland: Of course economics doesn’t really understand… I mean notionally, it has transaction costs, but they’re generally considered to be fairly trivial as a factor in behavior. But to what extent are Americans spending too much, for example, on replacing things rather than repairing them? Not because of the cost relative of one to the other, but simply because the emotional cost of actually fixing any… arranging anybody to come round and repair anything is like going through hell.

Roger Dooley: You know, you’re absolutely right. I know that we have made that exact calculation that trying to find somebody who would come out and fix it and probably do a good job was just so incredibly difficult, where people don’t even call you back. They say, “Oh yeah, we do that kind of work.” And then you don’t hear from them. Just all these frictional elements in it. It’s easier just to say, “Okay, yeah. All we’re going to be doing is putting money into an old one. Let’s just get a new one, and get rid of the old one,” which is not always the best choice.

Rory Sutherland: Do you want an extraordinary story, which is literally true? I nearly bought an apartment in France. Now, to an economist a transaction cost is a small sideline thing, which is largely considered irrelevant to factors like price and utility. I didn’t buy the apartment in France because the realtor didn’t phone me back. When you look at it, at the time, I was, “All right, okay, screw it. If he’s not going to call me back, I’m not going to buy his bloody flat.” That’s crazy when you look at it, isn’t it? A especially with that level of import, which was a five to six figure dollar amount, with a purchase of an apartment in the Pyrenees. And the reason I didn’t buy it, having been convinced that I wanted to buy it, was because the guy didn’t phone me. Now an element of that is also trust, which is. “What’s going on here?”

Rory Sutherland: By the way, that failure to call back, there are certain behaviors, if I had my way, I’d revamp the entire education system, and I’d have six months of education. throughout the UK and throughout the U.S., on things you must never do in customer service. One example is, I noticed it because it happened to be again about three weeks ago. You have a shop that’s open. I don’t know if this happens in the U.S. It happens occasionally in the UK. You have a shop which is visibly open, and you walk in through the front door, and they say, “I’m sorry, we’re closed.” Now what’s interesting about that is that logically it should be very trivially different than merely having a sign saying, “closed,” non the door of the shop. You turn up. You’ve been to the shop, and then you see, oh dear, its closed. When they allow you to go in, and they say to you in person, “I’m sorry, I’m closed,” something in our evolved psychology takes it as a personal slight, or an insult, which is, had you been richer, more attractive, less fat, or whatever, we would have sold you something. But to you, we’re closed.

Rory Sutherland: When I was a kid, that happened to me on a shopping outing in Abergavenny. There is a place called Abergavenny, I promise you, near to where I grew up. It happened to me in a shop when I was 17. For 20 years I didn’t go into the shop. I boycotted the shop. I boycotted a dry cleaner in Seven Oaks because I turned up at two minutes past five to collect my dry cleaning, and they said they were closed. Now had the store been visibly closed, I would have been annoyed, but I would have partly blamed myself. To allow someone to go in through the door, and then say we’re closed… Failing to call people back is also something which actually factors pretty highly on that-

Roger Dooley: Well, it’s like an emotional rejection beyond just a… the way businesses-

Rory Sutherland: … and is doing this. One of the things I love about behavioral science is I think it’s scalable. One of the things that irritated me about working purely in advertising, was you could be quite useful to people that had five million dollars to give to Rupert Murdoch and media budgets, but you weren’t much use to a café. What I absolutely love about behavioral science is you can take the same principles… It’s fractal really. You can take the behavioral principles and apply them to a small café.

Rory Sutherland: In my book, I have a little section… I want to advise your listeners, by the way, the book in the U.S. has a slightly different title, which is I think, The Curious Art and Strange Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business and Life. But Alchemy is the main title of the book, both in the U.S. and in the UK.

Roger Dooley: We’ll wink to as many versions as we can find in the show notes, Rory.

Rory Sutherland: The interesting there is that I made the point that the café around the corner from me, which put movable furniture out on the pavement, suddenly started doing much better than it had under the previous owners where it had fixed furniture. My hunch was that to the inference seeking human mind, having furniture which people could steal, or which could get blown around in a gale, was a very, very visible, long distance, costly signal that your café was open right at that moment. Having fixed furniture merely meant, well we’ve just left these heavy benches outside because they’re too heavy to carry inside. I’m convinced there are hundreds of cafés all over the country which, if they just a come in approach to street furniture, could actually restore their fortunes by making the fact that they were open highly visible and intuitively obvious at a distance to people 500 yards away.

Rory Sutherland: Now notionally it’s a form of advertising. It isn’t what you think of as advertising because we think of advertising as giving money to Rupert Murdoch to place ads in the paper. But the extent to which I think we draw inferences from behavior, and behaviors which are inherently truthful, by which I mean, you wouldn’t be closed and have stealable furniture, chairs and tables, sitting around overnight outside your café. Those signals are disproportionately powerful. So understanding positive signaling, which is a notion that comes as much from biology as it does from economics is a really, really useful thing, even if you haven’t got what you think of to be an advertising budget. Even if all you’ve got is the potential to signal in some way that you’re open. Then I think understanding the way in which people really make decisions in the real world, not the ludicrously oversimplified way in which economists would deem people to make decisions.

Roger Dooley: Right. I think that’s probably a good place to wrap up. I think the point about behavioral science strategies applying to any size business is what drew me to the area too, because I got my start in this space looking at neuromarketing, which at the time was pretty much a province of big brands. The Coca Colas, and BMWs who could afford these rather costly techniques to valuate advertising. But I found was that when I talked about some of these techniques that could be used by any size business, that’s what really engaged far more people because there are obviously far more small businesses than big brands. But, let me remind our listeners that today we are speaking with Rory Southerland, Vice-chairman of Ogilvy and author of Alchemy, Surprising Power of Ideas that Don’t Make Sense. I highly recommend this book. It’s entertaining. It’s informative, and if you are going to have surgery, you will learn why you ought not to pick the handsome doctor, but pick the less attractive, or perhaps less well groomed one. This could really save your life. Rory, how can people connect with you?

Rory Sutherland: Very easily actually. On Twitter is the best first place. I’m @rorysutherland. And I’m a fairly assiduous Twitter user. Twitter is very valuable for one particular thing, which is better than any other social network, it connects disparate groups of people. And I see the behavioral science. First of all, I got to be clear about this. I don’t claim for a second it’s the answer to everything. What I do claim is it’s a new way of looking at the world, which is disproportionately valuable because it gives you a completely new take on what might be the cause of a problem, and may stop you, by the way, making terrible mistakes like going, “The product’s not selling, we must drop the price,” which is essentially what economics tells you to do. It probably will sell more of your product. It is the most expensive intervention, particularly if you’re selling through intermediaries like retailers. Dropping the price is the most catastrophically expensive decision you can make, if it’s the wrong decision. But economics has caused people to make that the first port of call, which is disastrous, and terrible when you think about it.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well as B. J. Fogg said, “Motivation is expensive compared to other kinds of interventions,” and dropping the price is definitely motivation but it’s definitely expensive.

Rory Sutherland: And so, the removal of obstacles. The other reason I think that Twitter is important is I think, I know that E. O. Wilson for example, with his idea of sociobiology. There are a bunch of people who believe that there is somewhere out there the foundations of a new kind of science. We have lots, and lots of disparate schools of economics. Just economics, for example, as evenomics, which are all in a sense, this isn’t schools, but looking for, I think, a unifying brand.

Rory Sutherland: What I think is important here is that Twitter by bringing together people with business experience, people with academic experience, people whose background is biology, people whose background is statistics, people whose background is mathematics, people whose background is physics. We will only get to progress in that kind of new field if there’s quite a lot of overlap between different specialists. I was earlier on plugging that book Range, which I consider to be… I should start plugging my book, shouldn’t I? But Range is really an extraordinarily good… compliments to my own efforts, should I say.

Rory Sutherland: Why I think it’s important is what we’re starting to find out is that some of the things that economists are wrong about, they’re actually wrong because their idea of rationality is mathematically wrong. Even before we’ve got to the is business of evolutionary psychology and what the human is evolved to do in terms of it’s risk assessment. One of the fascinating things that a friend of mine called Ole Peters that the London Mathematical Laboratory is doing is he says that nearly all of economics is assuming an ergodic environment where the time series probability is the same as the aggregate. So it’s imagining a world of parallel universes and that the gain or mass is equivalent to averaging out parallel universes and then dividing it by the number of universes, as it were.

Rory Sutherland: Now when you’re making decisions over time, what is an actual approach to risk, is very, very different. So I’ll give you a very, very simple example of this. If I offered a thousand people a million dollars to play Russian roulette once, a few of them will be interested. If you offered one person a billion dollars to Russian roulette a thousand times in a row, no one would do it, because you’re going to end up dead. Now in the same way, our approach to risk given how genes exist and replicate has to be optimized for a non-ergodic environment where path dependency and time series matters.

Rory Sutherland: Therefore, in many cases in fact, what I think evolutionary biology is doing is going… Before we get obsessed about really complex explanations here, is it just that the mass was wrong to begin with? Now Ole Peters would claim, as indeed did Kenneth Arrow, as indeed Npapi published with Murray Gell-Mann. They all say, “Look, you’re using the wrong maths here.” If physicists were conscious of this distinction 50 years ago, economists had never taken it on board, your conception of what’s rational is different.

Rory Sutherland: So, I’m just going to take an example of a behavioral science thing. This isn’t the Sean Calib’s explanation. We don’t cross town to save $50 or $30 on a $2,000 TV, but we would cross town to save $50 on a fridge, which was $100. I’m talking about a small fridge, which is $150. So to buy something for $150 across by going in your pickup truck and parking outside the strip mall… Big fan of the strip mall, by the way. I think it’s an evolutionary mechanism, where eventually you get the right combination of nail bars, copy shops, donut shops, coffee shops and somehow you’ll reach some sort of stable equilibrium.

Roger Dooley: Some say they are the bane of our existence as well, but they offer a kind of convenience to people.

Rory Sutherland: It’s very fashionable to despise them but from an evolutionary point of view, I think the strip mall is actually quite interesting, because it offers, if you think of it, is variation and selection, isn’t it? And variation and selection in combination, which is interesting. If you’re a UPS store do you want to be next to a nail bar or sushi, but the experimental capacity of a strip mall interests me.

Rory Sutherland: But now the interesting thing, on of the things the scene would say is, “Look, you don’t buy a television very often, but you might by cheaper goods very frequently, therefore the cost to you of being a little bit extravagant buying a TV locally is much, much lower, and over time, then being completely spendthrift about whether you’re paying $150 or $200 for a fridge.

Roger Dooley: Now Rory, I want to be respectful of your time, so I will let our audience know that we will link to both your Twitter profile, your book perhaps in variations, and any other resources we talked about, including some of the great books that you brought up, Rory, on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. And Rory, I just really enjoyed Alchemy, and I know it’s spot on for our listeners. Thanks so much for being on the show, and sharing so much great info.

Rory Sutherland: It’s a joy. Thank you. Anytime. Really, really happy. See you in Austin one day, too.

Roger Dooley: I hope so, Rory. Or in London.

Rory Sutherland: Right here. You do need a train service to San Antonio. Once a day in three hours, seriously guys. Okay?

Roger Dooley: The European’s do that right. We could connect all of Texas’ great cities with a high speed rail, and it’s been proposed, but it’s not anywhere near being completed, or even initiated yet. Rory, thanks a lot.

Rory Sutherland: Always a pleasure. Thanks ever so much. Bye, bye.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book Friction is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to rogerdooley.com/friction.