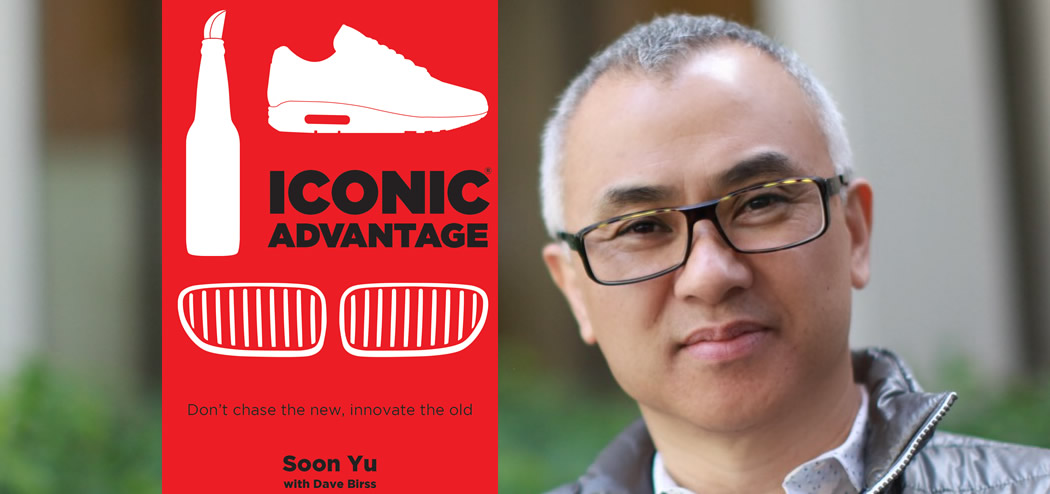

Today’s guest is an international speaker and bestselling author on innovation and design. Most recently serving as the Global VP of Innovation and Officer at VF Corporation (a parent organization to over 30 global apparel companies, including The North Face, Vans, Timberland, and Nautica), Soon Yu regularly consults for business leaders on developing meaningful Iconic Signature Elements, Signature Moments, and Signature Communication.

Soon has been featured in the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Entrepreneur Magazine, and New York Times, and he joins us today to share valuable advice on to how to build a brand’s iconicity. Listen in to hear tips from his new book, Iconic Advantage®, and learn what it really takes for brands to become iconic.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The three qualities that make brands iconic.

- What people need to consider for getting a brand noticed.

- How the internet and social media affect the process of becoming iconic.

- New opportunities for creating brand distinction.

- The two big aha moments Soon had when doing research about achieving iconicity.

- How to use iconic brand language to keep a brand relevant.

- What brands should figure out during their early days.

- The major mistakes most marketers make when trying to build brands.

Key Resources for Soon Yu:

-

- Connect with Soon Yu: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter

- www.IconicAdvantage.com

- Amazon: Iconic Advantage

- Kindle: Iconic Advantage

- Audible: Iconic Advantage

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to The Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is an international speaker and bestselling author on innovation and design, who’s been featured in the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Entrepreneur Magazine, and New York Times. Most recently Soon Yu served as the global VP of innovation at VF Corporation, parent organization to over 30 global apparel companies, including brands like The North Face, Vans, Timberland, Nautica, and Wrangler. There he established three global innovation centers and created a $2 billion innovation pipeline. Soon also lectures at Stanford University and is an adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design. His new book is Iconic Advantage. Welcome to the show, Soon.

Soon Yu: Thank you for having me on, Roger. It’s exciting to be on your program.

Roger Dooley: So, Soon, one item in your resume I didn’t mention was that you left a consulting job at Bain to found a business called Gazoontite.com back in 1998. And it sounds like the German word for what you do when somebody sneezes, but it’s actually G-A-Z-O-O-N-T-I-T-E, which is I guess a great dot-com era name. What’s the story there?

Soon Yu: Surprised you brought that up! Yeah, it feels so long ago. That was about 20 years ago actually. And yes, I left both a pretty nice paying job, both at Bain and also at Clorox; I took an 85% pay cut to actually learn about retail, because I wanted to start a retail concept focused on selling products to people that had allergies and asthma. And these are products such as hard goods, like obviously air purifiers and humidifiers, but also soft goods like beddings and hypoallergenic sheets, to also health and beauty aids that were really focused on people that had allergies.

And to learn retail, which I didn’t know anything about, which this really required because these are pretty new products to the world. And I had to actually quit my job. And prior to starting Gazoontite I worked at Crate & Barrel making five bucks an hour, for a whole year of just trying to understand what it was like to do a retail job. Very tough! Let me just say it was really tough.

Roger Dooley: Well that’s a real sacrifice, Soon. Did you get enough perspective on retail from that? Because it sounds like sort of an entry level type job there.

Soon Yu: Yeah. It was great. I got the full calendar of, I guess retail events; everything from obviously going through the holidays, to doing inventory counting, to the slow summer, all that. So it was a great learning experience.

And probably the thing I learned more than anything is that the retail job is actually so much harder than any white collar job I’ve ever, ever done in my life. You’re on your feet for eight hours, and the person coming into the store in your eighth hour wants to be treated like the first customer of the day, and somehow even with you achy ankles and feet, you’ve got to find it within you to greet them and to really help them out in the same way you would treat the very first customer in the morning. And that was tough!

Roger Dooley: Yeah, no doubt. With that education under your belt, then you went ahead and started Gazoontite?

Soon Yu: Yeah, actually while I was doing the retail thing, in the evenings I was writing the business plan. And actually every morning before I got to work I’d spend two hours on the phone calling anybody that would listen to me, or at least I’d leave a lot of voicemails, to see if I could raise some funds. And yeah, it was a very trying process, because I would say, 95% of the calls I made were basically calls that never were returned. And so that was my first two hours, then I’d work for eight hours straight, and then I worked on the business stuff for another three or four hours every night, and that was my life for about a good 12 months before even starting a startup!

Roger Dooley: Well I think that’s an experience that probably many of our entrepreneurial listeners can identify with. And I too was there for a while, working on my day job during the day and then spending all my available other time working on something else, a startup. So that’s great. So, how far did Gazoontite get?

Soon Yu: You know, it had a couple of iterations. We launched, and back in ’99 when we launched we were the very first kind of retailer that actually opened with a website and a catalog, and all of a sudden … You know, the intent actually was to be retail, but if you’ve ever tried to build something physical like a retail store, it takes a long time; it took us nine months from when we signed a lease to when we could actually open the doors. And you know, like every kind of remodel or house build, there’s peaks and valleys. And during the valleys, when there wasn’t much to do, we decided to put all our merchandise online.

And so the day we actually opened the store we opened the website and we just became the poster kids for this idea of bricks and clicks, or multichannel retail. And we really rode that for like a good two years, and then like everybody else in early 2000, you know, we didn’t have the right fundamentals. I think we were chasing a lot of revenue but paying for that revenue versus really earning it. And we became all of a sudden the poster child of what not to do, and we went bankrupt like everybody else, and we had layoffs, and it was really a painful period.

But fundamentally, myself and a few of the original investors, really believed in the concept of trying to help, especially, kids with allergies and asthma. And so we bought the company out of bankruptcy, and we ran it for another five years, and eventually it was purchased by a company that I went to work for as part of the deal. A big company, you probably know about, Clorox. And so yeah, that’s kind of the three lives of Gazoontite!

Roger Dooley: Yeah that’s a great story, Soon, but let’s talk a little bit about the ideas in your book, Iconic Advantage. Now the book is intended to help brands increase their iconicity, which I didn’t even realize was a word I guess, but it’s a good word.

Soon Yu: It wasn’t until we created it!

Roger Dooley: Yeah, that’s okay. So, every company wants to be like Apple or Nike or Coke, but is being iconic limited to a tiny number of huge brands?

Soon Yu: No actually, that’s one of the, there were sort of two big a-ha moments when we did some of this research.

The first is exactly what you’re asking about. Iconicity lives in the mind of your audience and your users, and you can be iconic with the smallest universe in the world. If, for example, you just wanted to be iconic, I live in San Francisco area, so one of the pizza parlors…

Roger Dooley: An iconic city, too.

Soon Yu: A very iconic city! Yes. One of the pizza parlors there didn’t want to be a Coke or a Nike or an Apple, they wanted to be iconic in Potrero Hill; that’s all they cared about. The district of Potrero Hill in San Francisco. And so there focus was, how do we create iconicity within that small universe. And so what they developed is sourdough crust pizza.

And it’s amazingly delicious; it also fits sort of the whole profile of San Francisco. But they, while it started off being really iconic in Potrero Hill, and pretty soon they became iconic throughout San Francisco. But their whole goal initially starting was just to be iconic in Potrero Hill.

And when I talk to B2B customers, and sometimes they tell me, “Look I only have 20 customers I call on,” I go, “That’s fine; why don’t you be iconic to those 20 folks?”

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So, you start the book, Soon, with two stories: American Apparel and Mini Cooper. How would you contrast the experience of those two brands?

Soon Yu: Wow yeah, I mean, exactly right; one is a tale of woe and the other is tale of actually taking an iconic brand and reviving it, and so a tale of success.

And the first one obviously is really about American Apparel. And that’s one where, in the book we talk about, you know, there’s three qualities that make brands iconic, and the first is the fact that they are distinctive and they’re noticed for something that’s unique about them, that’s memorable, that’s differentiated. And that’s sort of the first quality.

And then the second quality then is, whatever they’re noticed for, whatever they’re distinct, is that highly relevant to your audience; is it beneficial, is it meaningful? So, distinctive relevance. And then the last one is, within your universe, it could be the whole world or it could be 20 customers, are you recognized for that distinctive relevance?

And so when you think about this, are you being recognized for your distinctive relevance, and you look at those two stories, the first one is really about, “Hey look at me. Look at me. I want to be noticed!” But being noticed for all the wrong reasons, for all the wrong things. And that was very much about the founder, a Dov Charney, his focus on really being noticed for his unique personality, his, I don’t know, let’s call it racy lifestyle. And things that weren’t really related to the brand itself and to the benefits of the brand. And so that was a story of being noticed for the wrong things.

Whereas on the second story, which is really about Mini, Mini Cooper, and the fact that BMW sort of bought them out of bankruptcy. What BMW did first and foremost was really try to understand what about the Mini was distinctive, that was highly relevant to the people that loved the Mini? And their first job was to go and uncover that, and then protect it, and then revive it. And so that was a story about taking something that was honestly wonderful, the distinctive relevance that Mini had, and figuring out a way to keep it fresh and new.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and BMW certainly did that. In fact, I think elsewhere in the book you talk about things that look like faces, and that’s something that the Mini was known for, where one of their ads actually put it in a stadium, sort of a gimmick, surrounded by people, and it looked like this sort of large sort of pleasant face there surround by all the people in the stadium. But they managed to keep the appeal of the original vehicle, which was that kind of a quirky little thing.

Soon Yu: Amazing that you picked up on that. In fact, one of the very first things that the BMW brand did was kind of pull apart the DNA of what made the Mini distinctive. And believe it or not, Roger, the first thing they looked at is, the face. They said, “You know what? The Mini, actually more than most cars, looks like a face.” And so they actually created an iconic brand language around that actual face. If you ever look at their documents they show the face, and they show right next to it a child. And underneath that is three qualities: playful, eager, alert. And so that’s actually the first part of their iconic brand language, is the face of the Mini, and protecting it to be childlike.

So, it’s very interesting that you picked up on it. They had some real famous designers figure that out, and you picked up on it in two seconds. That’s- …

Roger Dooley: Well, I don’t know that I came up with that conclusion totally by myself, but you know, other folks have noted that. And it’s something that certainly, automotive manufacturers have used. Mazda’s got sort of an interesting face design on many of their cars. All seem to be smiling. So, I think everybody has to have their design elements. Now, not all products lend themselves to being faces, but they may look like something else.

You know, we’re talking about brands that have been developed over decades in some cases, but how is the internet, social media, mobile, affecting these branding elements, and the process of becoming iconic, Soon?

Soon Yu: Well, that’s a great question because, the world’s changing. And so, you know, does the rules and principles of being iconic still apply? I think the rules apply, but now there are new tools to actually bring these tools to life, and also sometimes the impact and speed of some of these principles can be brought to life much faster.

So let’s go back to those three principles. When you think about it, the three principles around one, creating great noticing power for that distinction; and number two, creating great staying power for the relevance. Like you said, to really reach iconic status, it’s not good enough to be relevant today or yesterday; you have to be relevant in the future. And so it’s this idea of creating timeless relevance, and that’s why call it creating staying power; you want to stick around.

And the last one is, once you’ve got great noticing power for distinction, and staying power in terms of, call it timeless relevance, then you want to scale it to as many people that can see it as possible so that you get as much recognition as possible. And we call that scaling power.

So when you think about the internet, the new tools that are out there, the digital economy and the way consumers interact, I think a couple things impact this idea of noticing, staying, and scaling power.

In terms of noticing power, I think more and more people have to think beyond sort of the physical product, or even the service interaction. I think people have to think about, how are they creating noticing power through apps, through the interaction through digital, through customer engagement in terms of feedback and reviews. Those are new opportunities that actually create distinction. And so I think what the digital age and the new economy have done, is actually created more opportunities for you to potentially create signature elements and a signature footprint.

On the second part on both the staying power and the scaling power, I think there’s just more and more tools now to both engage with your customers, in terms of creating this idea of relevance, and then lastly in terms of scaling power. I think what’s happened is, because with these online platforms being as distributed as they are, people can actually create iconic brands almost overnight.

Now, the true tests will be if they stand the test of time. And you know, in five or ten years we’re still talking about them. But at least in, I would say, within let’s say the current conversations, people like Uber, people like Airbnb, have become iconic fairly quickly, like within a year or two. And now the key is to see whether or not these folks will stick around. But yeah, I think the digital age has helped some brands come to scale and come to recognition really fast.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, Uber certainly became iconic, but it seems like they suffered a little bit of the American Apparel disease there, at least from a management standpoint.

Soon Yu: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Roger Dooley: Which is too bad. Although I think maybe the difference is that their product, their service, is actually highly useful and people love it. And I haven’t bought any American Apparel products, but I would assume that it’s pretty hard to differentiate a T-shirt or something compared to its competition. I mean, you can differentiate it by your marketing, which they did with these sort of very sexy, super sexy ads some people found offensive, and so they really got noticed quickly. But it seems like the product itself, how distinctive can it be?

Soon Yu: No, I think you’re absolutely right. Now, obviously, I’ve worked in the apparel industry and therefore worked in a lot of…

Roger Dooley: You would think that you can make apparel distinctive?

Soon Yu: You can. I mean there’s a lot of different ways. But given their focus was really not around what I would consider materials innovation or even IoT, because now you can actually, believe it or not, infuse an entire computer within a thread of a hair. So you could actually weave in all your circuitry into clothes. And so it’s all possible within the next five or 10 years. But that wasn’t their main focus obviously. Their main focus was really around just building cotton T-shirts and cotton clothing.

And one of the things that they were really known for was really good employee relations, really taking care of their employees, really making a statement about, you know, the social impact of having manufacturing in the US. Those were the early days, and I think what happened is they just got caught up in some of the other stuff. And if they would’ve stayed focused on what does it mean to be made in America, the pride of not just ownership but the pride of origin, the people behind it, the stories behind those people, the stories behind those communities. Over time people would recognize and know that and there would have probably been a sense of pride around that type of distinction. And so, unfortunately they didn’t go that route.

Roger Dooley: Well you just mentioned the word “story,” and that’s been a really powerful thing lately. We’ve had a few guests on the show who wrote entire books about story and the power of stories. And certainly many others who have incorporated the importance of using story into their work. How does using story fit into your framework?

Soon Yu: Yeah, I think story is really at the center of creating iconic advantage. Let’s just sort of step back and think about the word, and then the idea of icons. You know, icons are things that we had early in our culture; I mean, go back to the prehistoric days of the cavemen, and they were using basically symbols to communicate on the caves, right? And the cave walls. And those became icons basically.

And so throughout our entire human history, icons have been an incredible part of of telling stories. You know, when you see certain icons, like when you see the cross of the Catholic Church, it’s rich in story, and it’s symbolic of so many different things that we attach meaning to. And the way meaning is created is through stories, whether we tell the stories to ourselves, or whether somebody tells us a story. And that’s all these icons are; they’re just symbolic representations of stories, and they remind us of those stories.

And so all these great iconic franchises, what they’ve been able to do, is create what I call signature elements. And these are embodiments of their key point of difference of that brand, that service, or that franchise, and what those iconic signature elements do is just remind us of the stories of why we love this brand, why we like this product, why it’s a really good fit for our lives. Why it actually says something about us when we actually use those products. And you know, pull the veil on that, it’s all because of story. And whether we were told it, or we made it up, the only reason iconic products are so powerful is because of the stories that we have about those products in our heads.

Roger Dooley: You just Jack Daniels as an example in the book, and I think that’s probably a good example of their sort of old fashioned, homespun Lynchburg setting …

Soon Yu: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Roger Dooley: You know, just sort of feel like you understand both their origin story and maybe that story is continuing on until today. Although I also have the mental image of some giant industrial thing with huge stainless steel vats. I don’t know if that’s really the case or not, but I know they have to make a whole bunch of that stuff, so …

Soon Yu: They do but I actually have been to Lynchburg and visited. And I will say yes, there’s some modern components of it. But you go to their facility, and you see the alcohol being dripped down like these really tall, I think charcoal, like vats and stuff, and those have been around for the last hundred years.

And so the facility, even though there are modern enhancements within it, the general facilities still look like it was a hundred years ago. And it’s very authentic. And a lot of the barrels they use and a lot of the equipment that they’re using is actually stuff that is heritage. And so it’s actually a really important part of the brand. So yes it looks a little modern, but you’d be surprised how authentic it actually also looks.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well that’s good to know. And I think even when companies have to scale up, as if they’re successful they inevitably do, if they can keep some of that heritage incorporated into it, both for external consumption, you know, for people who happen to be able to do a tour of the facility or something, or also for their internal people, for their employees, because it sort of gives them link to the heritage of the company.

Soon Yu: Yeah. I think that’s the whole key with iconic advantage and the ability to create staying power, is actually knowing what of the old to actually protect and keep, and what of the old to actually use to marry with the new. It’s that balance between knowing what’s important of the old and marrying it with the new that actually creates great staying power.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, another example in the book that actually was a surprise to me, I enjoy the occasional martini and it’s Hendrick’s Gin. And I didn’t really know that much about the brand and I had assumed that it was a rather historic brand, but in fact it’s historic mainly in appearance, right?

Soon Yu: Yes, I mean they do a really good job in terms of really leveraging symbols and fonts and art that brings us back to, you know, the early ages of what I would consider, you know, creation of the industry. And so yeah, they’ve done a real smart job in terms of using iconic symbols that bring that about. But I would say the benefit of doing that is they’ve really made gin a really big deal now, in that location of the world.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I know your book is not about the spirits market, but I found it interesting that now there’s more gin produced in Scotland, at least for consumption in the UK, which, I always associate gin as being like, well in England I guess, you know, a totally English drink.

Soon Yu: Yes. No, I think that’s exactly the outcome of great iconic branding and also the ability to lead. I think what they did is they some borrowed equity; they borrowed the equity of the category and of other categories to really create the perception.

Roger Dooley: As long as we’re on that topic I’ll throw out one other thing. There is a gin called The Botanist that comes from Islay, where they distill those really smoky scotches. They too have created kind of a cult following I think, partly because they’re the, at least they were, the only gin distilled on Islay.

Soon Yu: Oh wow that’s great. I mean, I’ll have to check that one out.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, so again, I think they’re partly leveraging that story, of this island that produces some of the most expensive and unusual scotches, and perhaps a little bit of that carries over to their brand.

Betting back to business, it’s been fun, Soon, but I suppose we should get back to business here. You talk about iconic brand language. Explain what you mean by that.

Soon Yu: So, let’s go back to that Mini example. And what happened was, the Mini was launched in the ’60s, and it really, you know, the original Mini really fit, I would call, the sort of fashion trends and the mindset of the swinging ’60s in London, kind of the Austin Powers mindset, right? But the issue was, for the 30 years that they were in production, they didn’t really change the car very much. So it had great noticing power, but they did not invest in what I would consider staying power. In other words, what do you do to marry the old with the new. They kept the old pretty sacred. And because of that they unfortunately went out of business, and that happened in the ’90s; in fact the last car that came off the production line pretty much looked like the first car that came off the production line 30 years earlier.

But luckily BMW bought them out of bankruptcy. And their whole focus was on figuring out this idea of, how do you really keep that brand relevant, and how do you infuse newness into the brand? And so they really worked on the idea of taking what was important about the brand, the signature elements, and creating an iconic brand language around those signature elements.

So the face is part of that. The other thing that’s also part of it, there’s six elements; I’ll describe one more element. They looked at it and it had this idea of, it kind of looked like stacked hamburger; it looked like a Big Mac when you look at some of the layers. And so, there’s actually a hamburger that’s been stacked as part of their iconic brand language.

And the goal with the iconic brand language is two things. One, it’s letting you know what of the old that you should be protecting. What are those signature elements that you should be keeping sacred? But it’s more than just a brand guidelines document. We’ve seen those, right? Those are all about, the font should be this, the color should be that.

Iconic brand language documents also have another whole side to them, which talks about yes, protect this old stuff, but here’s how you play with it to make it new, fresh, and exciting. So there’s a whole section about what to play with. What about it should we be innovating? What key benefits do we need to keep, you know, like I say, innovate the old? What do we keep innovating against so that we keep the competition at bay? What do we do in terms of adding new style and new freshness and new design into the franchise? And lastly, what new stories are we going to tell to keep our customers both engaged with our heritage, but also engaged with where we’re going in the future?

And so, the idea of, where do you play on innovation, where do you play on design, and where do you play on storytelling, along with knowing what you protect, is the centerpiece of creating a really strong, iconic brand language.

Roger Dooley: How would that work for a new, perhaps smaller business? So, you gave the example of the pizza shop in San Francisco. Somebody is starting out, do they need to develop this same type of document or understanding?

Soon Yu: Absolutely. Put it this way, early on I think there’s opportunities for folks to pivot, to find themselves. Even in that early process it’s good to have the framework in mind to be conscious of it. And what I would say is, during those early days one of the things you want to ultimately come away with is, what’s your signature? What is it that when you leave the room, is the fragrance that you leave that people you remember you for?

I oftentimes work with startups and I work with CEOs, and they’ve got great ideas and they’ve raised a lot of money, and they say to me, why would I want to create iconic advantage now? I’m just trying to scale and trying to get to the next funding round. I go, yeah definitely do that, but at the same time, most of these companies I look at are usually in two- or three- or four-horse races with similar competitors in the same space, doing it slightly different, but overall, they’re all trying to beat each other in terms of either getting bigger faster, or coming out faster, or having some secret sauce technology that they can talk about. And I always say to them, “You know, it’s not always the biggest or baddest mousetrap that gets the mice. It’s the one with the stinkiest cheese.” So I say, “Guys, are you working on your stinky cheese?” And they look at me and go, “Wow, no, we never thought about it like that.”

So how do you create fragrant, stinky cheese? How’s your storytelling? Do you know what makes you different in the stink and are you telling stories around that? Are you continually innovating what makes you distinctive and unique? And how are you infusing new ideas into that?

And so this idea of what’s your signature works at any level, whether you’re Fortune 500, or whether really you’re just somebody who has set up shop on the local mall or on your local main street. It’s really important to have something that makes you memorable and distinctive. And here’s the key: once you find what that is, like I said, how do you play with it? How do you keep it fresh and exciting? And still protect what it is, but keep it fresh and exciting.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). To really abuse that metaphor then, had the pizza shop that you talked about said, “Okay, our distinction is going to be that we do sourdough crust,” and it turned out that early customers raved about their Limburger pizza, maybe at that point they’d step back and evaluate, “Okay maybe it’s not sourdough crust; maybe we need to really focus on Limburger pizza or on pizza with really unusual cheeses.”

Soon Yu: You know, that’s a good point if say they uncovered that. One of the things I would say is, as long as sourdough crust one, isn’t a negative, and two, it’s something that is part of their heritage, how would you mash the two up? How could you then create Limburg sourdough pizza, right? And so this idea of you know, again, marrying all the new stuff that’s working with some of your iconic signature elements. As long as the iconic signature elements are still working for you.

You know, there are times, I’ll say this, where it’s actually important to think beyond the signature element. You know, sometimes those are features; sometimes it’s a pattern or color; sometimes it’s a silhouette. Sometimes it’s an experience and sometimes it’s a point of view. There’s a lot of ways to create what I call signature fragrance or leave-behinds.

But usually those signature elements lead to something much more importanter, a signature benefit. So take a company like Amazon. You know, they kind of originally were started because of having the most books and the cheapest books in the web space. And they’ve expanded beyond that. But they, whether through-

Roger Dooley: Just a little.

Soon Yu: Just a little, Roger, okay! Whether through happy accident, or through intent, they actually handed something called One-Click. And so you click on that button and it’s already automatically shipping to you; you never even have to do the checkout anymore. And what they decided to do is, this is an incredible iconic element they own, and the benefit beyond this is something that they actually wanted to own beyond the actual feature. And so now, they took the One-Click and a few years ago they actually made it a physical One-Click, where they had the dash buttons where you could order, you know, Bounty or beer or whatever, right? And now, you can One-Click all your groceries, or your organic food. And guess what? You don’t even need to click anything anymore, you just say “Alexa I want ABC” and it’s already on its way.

And I guarantee you, by the time my son is even half my age, he’s eight right now, and let’s say in the next 15 or 20 years, he’s not even going to know that Amazon was a website, you know, with predictive analytics and IoT; he’s probably going to have a chip implanted in his brain, and Amazon’s going to know he’s going to want a Coca-Cola before he even knows he wants a Coca-Cola. Because in Amazon’s mind, they’re not worried about owning any type of iconic feature; they want to own the iconic benefit of no patience required. And if they can own no patience required, it’s game over for everybody else.

Roger Dooley: Good point. One last question, Soon. Where do you think marketers go wrong when they’re trying to build brands or thinking about building brands?

Soon Yu: So we talked about the framework of noticing power, staying power, and scaling power. And scaling power is usually, once you know what your distinctive relevance is, it’s the focus of getting it in front of as many people as possible. And you can do that through marketing, through distribution, or actually through extending your signature elements into new products and new families of products.

Here’s what happens: I work with a lot of folks, and I do one simple exercise in the beginning. After I’ve explained the framework, I ask everybody put down their top five to seven key initiatives that they’re working on that are obviously impacting their performance review or on their work plans. And everyone does that. And I then I say okay, let’s put those initiatives against those three powers in terms of where they fit. And over 80% of those little Post-Its that people put their initiatives on show up in the scaling power section. Very little of it is focused on what makes you distinctive and how do you keep that relevant. It’s all focused on let’s just advertise and tell people all these different things about us.

And so I think that’s one big major mistake. The other big major mistake is, a lot of the scaling power, or a lot of the marketing and distribution, and new product extensions, are not actually focused on celebrating your iconic brand language. They’re just focused on creating attention. And I think that’s where most marketers go wrong, is that they don’t understand what their iconic brand language, and they don’t understand that the role of marketing, distribution, and creating new products is actually to celebrate that iconic brand language.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well today we are speaking with Soon Yu, branding innovation expert and author of the new book Iconic Advantage. Soon, where can our listeners find you and your content online?

Soon Yu: Yeah, they can definitely check us out at our website at IconicAdvantage.com, and they can find me at Twitter, at @SoonSpeaks. And I would look forward to connect with as many folks and as many listeners as you have.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well we will link to those places and to any other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast. And we’ll have a handy text version of our conversation there too.

Soon, thanks for being on the show.

Soon Yu: Thank you very much.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion, and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.