Many of us think of creativity as an isolated incident – a flash of brilliance that inspires a bold painting or a perfect business decision. In fact, research increasingly finds that discipline is key to fostering creativity. Erik Wahl, entrepreneur and graffiti artist, joins us today to talk about his book The Spark and the Grind: Ignite the Power of Disciplined Creativity, and how order can help you come up with some of your best ideas.

Many of us think of creativity as an isolated incident – a flash of brilliance that inspires a bold painting or a perfect business decision. In fact, research increasingly finds that discipline is key to fostering creativity. Erik Wahl, entrepreneur and graffiti artist, joins us today to talk about his book The Spark and the Grind: Ignite the Power of Disciplined Creativity, and how order can help you come up with some of your best ideas.

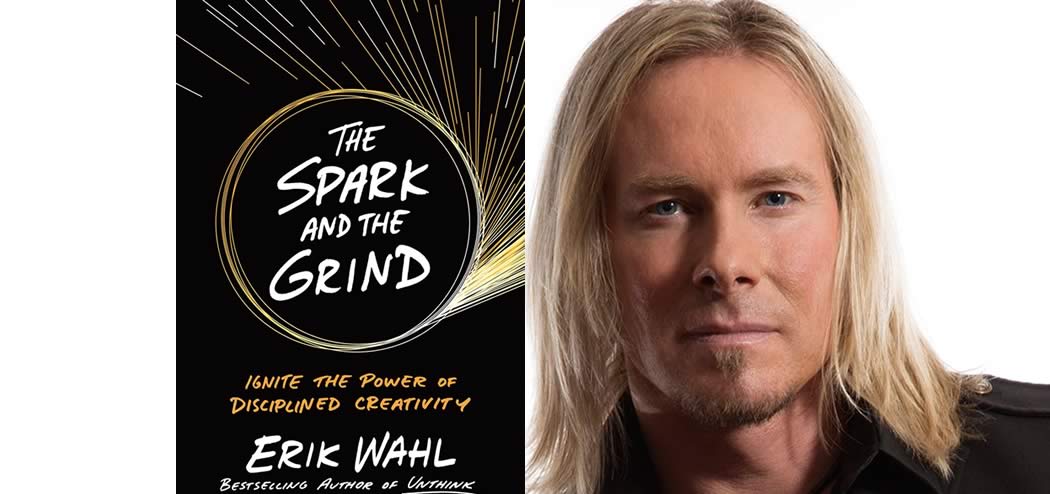

Erik Wahl is an artist, author, and entrepreneur. He is an internationally-recognized, thought-provoking graffiti artist and one of the most sought-after speakers on the corporate lecture circuit. He’s also the author of several books on boosting the creative process.

Erik begins by sharing his love of art and the core mission of his book – to dispel the idea that creativity is a fleeting, singular moment rather than a daily practice. We talk about the coexistence of strict routine and freedom of mind, and how artists and successful businesses alike apply these principles to their work. Erik also shares his thoughts on why it’s okay to keep a day job to protect your ability to create without commoditizing your work.

This is fascinating take on creativity, and Erik’s energy will make you excited to nurture those projects or ideas you might have been putting off.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Erik’s method of fascinating and intriguing his audiences.

- Why Erik believes it’s so important to accept disruption of the status quo as the “new normal”.

- How structure can help breed creativity in art, business, and other areas of thought.

- Why the combination of creativity and logic is more potent today than either of them wielded separately.

- The growing importance of emotional intelligence when trying to engage an audience.

- What internal barometers Erik uses to measure his success, and why he prefers this to external acclaim.

Key Resources for Erik Wahl and Sparking Creativity:

- Connect with Erik: Website | Twitter | Facebook

- Amazon: The Spark and the Grind: Ignite the Power of Disciplined Creativity

- Kindle: The Spark and the Grind: Ignite the Power of Disciplined Creativity

- Amazon: Unthink: Rediscover Your Creative Genius

- Kindle: Unthink: Rediscover Your Creative Genius

- Banksy

- Shepard Fairey

- Jeff Bezos

- Sergey Brin

- The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron

- Ernest Hemingway

- Kodak

- The 10% Entrepreneur: Live Your Startup Dream Without Quitting Your Day Job by Patrick McGinnis

- The Unexpectedly Smart Way to Become an Entrepreneur with Patrick McGinnis on The Brainfluence Podcast

- Creativity Surprise: What’s Really Blocking Great Ideas with Jennifer Mueller on The Brainfluence Podcast

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is Erik Wahl. Erik has a fascinating resume; he’s a best-selling author and sought after keynote speaker. We’ve had a few of those on the show, but I’m certain that Erik is the very first graffiti artist we’ve had. His work is recognized internationally in that space too.

Erik’s past books include “Unthink: Rediscover Your Creative Genius” and “Unchain the Elephant: Reframe Your Thinking to Unleash Your Potential.” His brand new book is, “The Spark and the Grind: Ignite the Power of Disciplined Creativity.” I particularly like Erik’s description; I’m speaking from his website, and I’m going to give you that verbatim: “This presentation is equivalent to yelling ‘CLEAR’ as the paddles are positioned to shock the fading pulse of your workforce and enliven their hearts to pursue their jobs as you both originally intended.”

Assuming that you’re going to keep listening, be sure you’re grounded because I think that Erik will jolt us all. Welcome to the show, Erik.

Erik Wahl: Thank you very much, Roger. Great introduction, and thank you to everyone who is still listening after they hear the fact that I am branded as both corporate thought leader and a graffiti artist. That is intentionally done to cause alarm, and we can talk about that a little bit more, but so much of it is about branding. So much of my writing, so much of my performing, so much of my sharing is all about channeling a message and how to fascinate audiences, how to fascinate viewers, how to grab their attention and intrigue and educate them from a little bit more engaging position.

Roger Dooley: When you show up someplace for a keynote, do they frisk you for spray cans, Erik? I mean, some of those vast concrete walls you see in convention centers and the like really have to be tempting.

Erik Wahl: Hey, you know what? Art has been really a place, it’s a sanctuary for me. And I didn’t start as an artist, I began as a business professional. I went to business school, owned my own business, didn’t even really explore the arts until after I turned 30 years old. I’m 46 now, so I’ve had 15 years, so I’m not a beginner any longer in the arts, but because I approached art from almost an analytical position early on, it was about fascination, and one of the most fascinating elements of art …

And I love all forms of art. Photography, sculpture, classical artists, Picasso, Michelangelo, da Vinci, but there was an element to street art that was meant for the people. It wasn’t critiqued by museums, or art galleries, or bought or sold, or commoditized, and so there was to me … I was drawn to street art because it was meant for the people. In the last hundred years or so, just the term “graffiti” has been hijacked by criminals, or vandals, or tagging, and there’s been a lot of disruption and negativity associated with it, but if we were to trace it back to its original roots, graffiti is how we etched, and scratched, and carved our legacy, and our heritage on cave walls; it’s how we shared our story.

For me, that’s what graffiti has meant to me. I intentionally chose it as an alarming or shocking part of my brand, even though it’s one facet of the type of art that I do. I do all kinds of different art, but that’s the one that as I was shaping my brand on the corporate lecture circuit was the one that got the most “ah-has.” It got, “Wait, you’re a what? You’re a graffiti artist who speaks about innovation and creativity to Fortune 500 companies? That’s fascinating. We want to know more.”

It continued the conversation, and I think that’s a lot about I think, you know, kind of what you’re doing with the science of waking up the mind, alarming Broca, getting people’s attention, and then almost seducing or wooing them into a further conversation, which is what I’m looking to do both with my art, as well as my writing, and my live performances.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, if you want to show a rejection of the status quo and sort of a change in thought process, graffiti is probably better than say, oil painting or something. You know, it just has that sort lack of rigorous discipline, and a much greater sense of, “This is something different and out of the ordinary.”

Erik Wahl: It has almost, you know, it’s been associated with anarchy, or disruption, and again so much negativity has been around that, especially with those words. However, we look at what’s going on in our culture, in our economy, in our global political situation; we’re experiencing amazing disruption and almost bedlam or anarchy, but we’re trying to figure out how to gain solid footing.

And so now more than ever, I think it’s important to really focus on elements, and stances, and positions that were able to gain traction; understand that this disruption is the new normal, and so if that’s the case, how do we step forward with confidence proactively, as opposed to constantly reacting to what’s happening around us?

And so even though I came up with this brand 12 to 14 years ago because I was inspired by Banksy, and Shepard Fairey, and a lot of the, I think, truly clever street artists, it’s more relevant today. It’s even gained an element of hipster coolness to it that wasn’t foreseen, but it’s been something that has been very, very fun to ride this wave of disruption, and helping people cope with and embrace disruption, actually as a competitive advantage, as opposed to just a reeling uncertainty of chaos.

Roger Dooley: Well, let’s talk a little bit about creativity, Erik. I searched Amazon Books and found almost 40,000 books on the topic of creativity, and in the last month or two, I’ve spoken to a couple of different authors that have their own take on how companies or individuals can be more creative. What do you think is the core insight that “The Spark and the Grind” adds to this body of literature?

Erik Wahl: For me, it is the breaking the myth of creativity being a whimsical kind of lightning bolt strike moment. For me, and I’ve kind of experienced this through my entire life, but never really captured it in words. I’ve talked about it in my live presentations, but not put it into actual content, and that is: structure creates freedom.

And so it’s that almost militaristic discipline and routine, and accountability is what allows me the freedom of mind and expanded consciousness to come up with new ideas. It gives me confidence because I know I can return home to a place of security and confidence. So I have the freedom to explore and venture out, and take little mini-micro risks, or experience mini-micro failures and still return back to that very disciplined structure, and that disciplined structure is what is the catalyst that fuels or fans constant creativity.

I wanted to dispel the myth that creativity’s a one-off; you know, it’s meant for kind of people who are on the fringe, artists, poets, rock stars, people who have these … you know, they were born creative, and just have … creativity comes easy to them. Creativity’s a natural human experience; it’s almost an energy we all have from the time that we’re young and it systematically gets deprogrammed out of us as we become linear; as we become academic; as we become siloed or efficient.

And you know, that’s a very necessary part of human learning. We need to compartmentalize, we need to understand life through simplification and structure, but I think what happens is, is we become too reliant on that as a crutch and we become too myopic and almost develop tunnel vision, or ruts, or we say things like, “I can’t even draw a stick figure; I don’t have a creative bone in my body,” because we’ve become so analytical, and there’s a lot of … so many positive traits to being logical, analytical, pragmatic, conservative, scientific.

What I’m particularly leaning into now as we’re turning the page into 2017 is all of those things are absolutely, categorically necessary, in that logic discipline structure, but now more than ever, we also need intuition, and emotion, and authenticity, and trust, and creativity to be able to weave back into those analytics to activate them; to bring them to life, because there’s information overlord for everyone.

Through media, social media, interaction, marketing, even just our communication with our own organizations, it’s so much information, it’s hard, very hard, to get people’s attention and to get them to either buy, make a decision, or just gather share of mind. And so to me, it just makes me more and more curious on how to unlock changing consumer behavior, because what worked last year doesn’t work this year.

The successful patterns, and strategies, and tactics, and best practices that were written about in Harvard Business School 10 years ago might not apply next year, as we move to an increasingly social, mobile and cloud environment. And so as an artist, I’m looking for ways to continue to fascinate my viewers, and seduce them into being almost magnetically drawn to art from a “wow” perspective; to be able to begin a conversation that is important to me. Same thing with my speaking, same thing with my writing, is I want it to surprise Broca, to awaken the mind, to fascinate, to be able to get new ideas across.

Roger Dooley: Well, something that pervades the entire book, as I suppose people might gather from the title, is that creativity really involves two things: that spark, that is sort of the flash of inspiration, but then also the grind of working through the process of making it real, and neither is effective without the other, and also people tend to skew in one direction, and you talk about igniters, who might be highly creative and grinders, who are really good at grinding the work out in a very organized manner. Explain sort of the duality of that concept, Erik, and to people, are people stuck in a role forever or, how does that work?

Erik Wahl: The beauty of our human mind is that we are able to adapt. We do get stuck in patterns, and that’s okay as long as we can recognize that. And that’s where emotional intelligence, I think, is becoming the most valuable trait in school and in business that’s not really being taught or fleshed out, and that is self-awareness.

Being aware of our cognitive biases, being aware of our own narratives for how we’ve developed certain ideologies, certain patterns of thoughts, and being able to step away from those temporarily; not to let them go and say they don’t exist, but to suspend those temporarily, to be able to look at it from a number of different positions.

And so one of the things that I’ve experienced real time is I’m working in both worlds. Simultaneously I’m working in the artistic world, actively creating and sharing with artists, and I’m also actively consulting and working, and sharing in the corporate world with entrepreneurs, and it is this yin-yang balance.

They’re not polar opposites that are causing friction or that should cause friction, but rather they’re complementary forces that when working together, creates something entirely different and more powerful than any one of them could on their own, and we tend to say, “Yes, I’m more of a creative person,” or, “I’m more of an analytical person,” and we will have those positions, and that’s fine.

What I meant to do with this book is to share how they both work together, and how we have access to both, and it’s actually far easier for me to teach an analytical, logical, rational, scientific individual how to be more intuitive, and emotional, and creative, than it is for me to teach an artist or a naturally creative person how to be more disciplined, or structured, or analytical, and that’s where really a lot of creatives go awry is that they assume that they’ll create a beautiful piece of artwork, beautiful piece of music, and that the world should all think it’s a genius, and come to them.

And when they don’t, they become depressed. They become self-absorbed; this idea of the starving artist actually plays out into a reality because they feel like the world just doesn’t get them. They’re coming up with these brilliant ideas, but that they don’t stick, and the reason they don’t stick is because there is an element of translation that needs to take place.

They need to understand how the rest of the world actually thinks; how the analytical people think, how do businesses think, why they would spend their hard earned money to have part of this genius, or want to be a part of this art, or to participate or experience this art further, and so it’s an understanding of both, and the non-dual approach to creativity of “Yes, and” rather than “Either, or.”

I love it so much because there is so much structure and routine and discipline that takes place in my creative process, both in writing and creating a presentation, a live presentation as well as when I’m starting a new piece of artwork.

Roger Dooley: Now one thing surprised me about art. I mean, I’ve always thought about art as being, you know, just a very sort of exercise in creativity where, you know, somebody sits down with a canvas and some paint, and ideas fly up in their head, but I had a chance to work and be friends with a world-class sculptor for a while, and I was surprised at, really, what went into that process because beyond his artistic vision, he had to deal with things like metallurgy; he actually had a manufacturing process.

Eventually it became a construction project when it was installed on the eventual site, because he did some rather monumental sculptures. He definitely had both of those things going, just to survive in that type of art, and I suppose there are other artists too; certain kinds of performing artists that there’s an awful lot that goes into it beyond the creativity piece.

Erik Wahl: There’s so much militaristic discipline and engineering, and you know in sculpture, mathematics, and you have to understand costs, and there is ROI that takes place that a lot of times, artists don’t think about. And if they begin a project without understanding the scale and the costs, and the distribution, then they will go bankrupt; they will lose, and they will become depressed, and that happens again, and again, and again because their ideas don’t match with the planning and the actuality of what it takes to bring that idea to life.

That’s why they need to be addressed in that initial vision; that initial painted picture, for what you’re looking to create in the end, and we sometimes need to scale back some of the maybe size of the structure that we were intending to sculpt, some of the production, or lights, or sound that we were hoping to create in a theater; maybe some of the chapters of our book that I thought maybe was brilliant, but my editor or publisher says, “Hey, this would maybe be your second or third book, but we need to really hone in and focus, and make this precise and conceptual so that our consumer can take it in, and not just give them vastness.”

And so there is so much structure that takes place into translating a message effectively to scale, and that’s the beauty of art, the beauty of writing, the beauty of rhetoric, persuasion, marketing, and even building a business. It’s a game, and it’s a mystery, and I love the uncertainty of it because there is no formula; there is no exact pattern that worked yesterday that’s going to work tomorrow.

We need to have the mental dexterity and agility to be able to adjust, and one of the things that I learned as I became an artist, and this fascinated me more than anything else, was that art was not about producing a product, but it was actually more about producing thinking. And the more that I continued to go through the process of creating, the more ideas that I came up with in all kinds of different capacities; in photography, the way that I see, the way that I think, the way that I empathize with others, the way that I understand how consumers, our viewers or audiences respond.

I need to be able to adapt. I have one picture in my head, but then the actuality of it might be different, and I need to learn to be able to adapt on the fly, and that’s where I think emotional intelligence is so key, and now even more important than IQ or intellectual intelligence, although still very important, that awareness of being able to adapt our formulas, our vision, our hopes and dreams to be able to translate to an audience are really, really important.

Roger Dooley: That kind of goes in parallel with another point you make in the book, and that is how some great innovators like Jeff Bezos or Sergey Brin don’t sit around in an empty room trying to be creative. Maybe they do sometimes, but what they tend to do is actively dig into areas of interest by doing some real work there; placing some small bets, trying stuff.

And it may not all work, but what they’re really doing is finding out how the world really works and not just speculating, “Well, this is what I think people really want,” or, “This is what I think might happen,” and often when you do that, you find your original idea wasn’t so great, but you find that you come up with a much better idea.

Erik Wahl: What they’re continually doing is exploring, and whether you own a small business selling coffee mugs, whether you’re an artist, whether you’re a rock star, whether you’re an athlete looking for the best way to complete a play, it’s all about exploring new options. You want to be disciplined and have structure, but at the same time, have little mini-explorations going at the same time, because there is a wealth of new ideas and innovative ways to solve these challenges; new ways to navigate ambiguity, new ways to master complexity, but it’s all about exploration.

And when people say, “Oh, I’m not creative,” or, “I just don’t have a creative bone in my body,” I’ve kind of traced that back to … Any lack of creativity in our lives is really just a lack of curiosity, and it’s that curiosity is what fuels those explorations. It fuels those little mini-shots to Mars, or ideas.

Those are what are really exciting because once we ignite curiosity, if we can ignite curiosity in our students about history, about math, about science, then we’ve got them. Then they’ll become autotelic and they’ll want to explore for themselves. We won’t have to impose learning on them; they’ll be intrigued to want to learn on their own, so it’s that fascination and curiosity is what drives creativity, and new ideas.

Roger Dooley: You know, I find that in my own writing, it takes an approach something like that where rather than trying to plan out whatever it is that I’m writing completely at the beginning, I’ll start with an idea and then just dig into it. Depending on the nature of the piece, it might just involve doing some additional research, or if it’s something bigger like a book, I may start talking to people and interviewing people that are somehow related to my original idea, but I don’t really go with a rigid structure to begin with.

I mean, I think that most folks would say, “Well, if you’re going to do a business book or a non-fiction book, you set out the outline, and you know, sort of the chapter structure, then you fill in the blanks,” but I find it’s often a lot more interesting for one, but also you end up with better ideas when you sort of let the content, and your discovery, and your interaction with it take you someplace, perhaps someplace new and different.

Erik Wahl: Julia Cameron wrote a book called “The Artist’s Way,” which was very influential for me. I write every single day as a fleshing of thoughts, and I write without punctuation, without attention to spelling; it is really what I call a verbal vomit, and it’s just getting out ideas, ideas, ideas.

Then I go back and probably one of my favorite writers of all times is Ernest Hemingway, and kind of under that idea of then simplifying; so getting as many ideas out there as possible, and then carving, and shaping, and sculpting, and honing, and creating prose then that is almost to me … I like metaphor. I’m drawn to poetry, I’m drawn to narratives and storytelling.

So then how do I take all of these ideas that I verbal vomited onto pages, and then make them more concise? Make them translatable, and make them consumable? It’s the same way how I approach my speaking career is, I don’t go, I’m not a part of speaking associations, I don’t follow a structured outline for how people present; you know, opening thesis, three supporting points, and then a closing conclusion.

I’ve gone and studied comedians, and musicians, and live theater, and what fascinates and lights up an audience. And then I work from that formula and plug in actual content. So my goal is to blow audiences away; to catch them off guard and to delight them to the upside with “ah ha” moments, but through those “ah ha” moments is to give them some substance, and some actual takeaways that they can actually apply into their business, into their life, into their parenting, into their art, into their marketing.

That’s what lights me up about performing as well as that process of creating expanding consciousness, expanding imagination, and then reverse-engineering and focusing great discipline and simplifying and contracting, and making it consumable for audiences. So it’s again, that “Yes, and,” that spark of expanding into imagination and then reversing and contracting, and focusing into great discipline in the grind of executing.

Roger Dooley: There’s a lot of great stories in your book, and one that I found particularly interesting was the acclaimed chef whose restaurant had earned three Michelin stars, and then he asked that those stars be removed, which is probably a first in the history for Michelin. What was the thought process going on there? Why would, having achieved this pinnacle, would he say, “Okay, let’s not do that?”

Erik Wahl: The pinnacle was not the end goal. It’s the love of the process, the passion for the experience itself, and if we’re not living up to our own standards, then achieving goals, Academy Awards, New York Times best-selling books, that’s just stuff. But if we’re not feeling fulfilled personally by it, then I think that ends up being a real disconnect.

Until we feel it deep in ourselves, and I know … you know, I could do a presentation, and sometimes my wife and I laugh. She said, “How did it go?” I said, “I got a standing ovation, but it was a crappy show,” because I knew that I had more to give. I didn’t connect as authentically or truly as I wanted to, and I’m very grateful that the audience felt it, and that they were activated and brought to their feet in ovation, but for me personally, I knew that there was a little bit more that I could’ve given them, so I would’ve taken away one of my own Michelin stars.

I’m very grateful that it was received that way, but between my wife and I, we’ll share in detail, how did it really go? How did I really feel? How many Michelin stars did I get? You know, I’m not going to go back out there and tell the audience, “Hey, sit back down, I sucked. I can do better.” I have an internal grade for myself that’s different than an external grade, accolades, or financial success, or critical acclaim, or people saying, “You’re so great.” That’s not what I’m striving for, it’s an internal process of just the love and the passion of the game, and the process itself.

Roger Dooley: Perhaps there’s something in there too about … I think you probably draw a corporate analogy to that restaurateur, because sometimes we achieve something in a corporation, in our business where perhaps we’ve just got a dominant market position now, or we’re very highly regarded by our customers.

Suddenly, even though that’s great, we’re constrained by that because trying something new might cause us to lose that level of approval for whatever reason. I think probably one of the great corporate disaster stories is Kodak, where they had achieved really a tremendous market position; they dominated the film industry, and they were by and large a well-liked company too. They had a great record of innovation.

I mean, they basically had everything going for them, and they come up with the viable digital camera, but they were constrained by what they were already doing. Introducing that might’ve taken it away, and I think probably that chef felt a little bit the same way where, if he wanted to introduce a radically different menu in his restaurant, he might lose those stars, and so rather than say, “I’m going to limit my creativity to what will keep them,” his thought process was, “Okay, I’m going to start from scratch again and keep inventing,” which had Kodak done it, there might’ve been some risk involved there, but they might’ve ended up being one of the dominant players in digital. Anyway, that’s my take on that.

Erik Wahl: Well, and Kodak is a classic example for institutional complacency, and there’s so many more businesses that are experiencing Kodak moments right now that need to adjust; they need to disrupt themselves, and that’s again getting back to the fact that growth and comfort cannot coexist. We’ve got to become more comfortable with those mini-explorations, otherwise that institutional complacency is going to be the architecture of our downfall.

Roger Dooley: Now you do have a chapter too, why people should keep their day job to be creative, and that seems at first glance, counterintuitive. I mean, probably most people in some type of employment situation where perhaps it’s not all that demanding of their creativity or it doesn’t seem to be that demanding, fantasize about, “Boy, if I could just get out of this situation and sit around in coffee shops and art galleries all day, then I could really be creative.” Explain the thesis in that chapter.

Erik Wahl: Once we commoditize our creative process, it loses some of its passion drive. I loved writing that chapter because they don’t need to be separate. There’s a bunch of lovely quotes; “Do what you love, never work a day in your life. Do what you love, the money will follow.” And there a lot of truth to that, but finding those passions …

But there’s also, especially for artists and I think that chapter was written more for artists and parents of artists, or creatives, that there is very much a structured approach to being able to fund your creativity. If that means working at a job that’s able to create income so that you can develop plans and engineering, and structure, and buy materials so that you can create, that is going to give you new opportunities to see the world from different eyes.

So don’t begrudge or feel like the labor that you’re doing is without purpose. It is creating income and it’s generating a source of energy, by which to continue being creative. If you’re able to plug that back into your business and combine the two, that’s great, but don’t just bail on your day job because you think it’s boring, and you think you’re going to start making money just because creativity’s cool, or because you think you like art.

There is so much discipline that needs to be first adhered to before you quit that day job. You know, eventually, that might not be the job that’s the best fit for you, but until you know to structure on how you’re going to brand, market, distribute, shape, translate your message and actually make money, then you absolutely need to keep that day job to be able to exist, because we need food, we need shelter.

We need security, and we can’t bail on those, or else we’re going to become desperate in a hurry, and that’s where a lot of artists find themselves, is they have quit their day job to pursue their passion, and if their passion doesn’t work in the first three, six, nine months, they’re in a lot of trouble because they don’t have income nor do they have a sustainable career.

Roger Dooley: That fits in really well with … A few months ago, we had Patrick McGinnis on the show, and he wrote a book called “The 10% Entrepreneur,” and his was more basically focused on entrepreneurship compared to creativity, but the message was the same. You know, at the very least, make sure that you don’t totally screw up your entrepreneurial venture by not having the resources to keep it going, but also, sometimes there are some synergies or synchronicities that you can actually leverage your day job, and then end up having it be a win-win. At least the most basic level, you’re not totally setting the stage for your own personal financial disaster if things don’t work out as quickly as you expect them to.

Erik Wahl: I’m a far better writer because I’m a painter, because I see because I think differently, because I experience, so I’m combining the two. I don’t actually sell any of my art anywhere, I never have. I’ve never commoditized it, and fortunately I’m able to knock out the rent because of my writing and speaking career.

But to be able to keep my art pure, and de-commoditize it, because you can’t put a price on cool, and I always want my art to be cool, not commoditized. So I’ve separated those two and fortunately, I am in a very unique position where I’m able to make a living as a performer, and a presenter and a writer, and my art is just meant as explorations of my mind; to expand consciousness and to try and keep creating cool, shocking, alarming, seducing, amazing pieces of art.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, let me bounce one last question off you here, Erik. We’re almost out of time, but we had a guest on not too long ago who had an interesting take on creativity, and it was Jennifer Mueller, and her research showed that looking at, not individuals so much, but at companies and organizations, they all bemoaned the lack of creative ideas. Like, “Boy, we need more ideas,” you know, “What’s the number thing the CEO says is the problem? Well, nobody has any good ideas.”

Her research showed that in many cases, those ideas existed; they were killed early on and part of it is a sort of cognitive bias that we all deal with, where things that are unknown, which creative idea tends to be more unknown than the very sort of simple improvement idea, like making a machine run faster or adding a little feature to an existing product, even though there may not be that much more financial risk, just the uncertainty associated with it, ends up making our minds try and avoid it.

I’m curious, do you think that a big part of the creativity problem isn’t that there are no ideas, but that in fact, somehow, they die an untimely death before they get far enough to be valuable?

Erik Wahl: I would absolutely, categorically agree with that. We all have these amazing creative ideas, and you see them as you people are walking through the mall. “Oh, you know what would be a great idea? You know what that business should do? You know …” We have these, but unless those ideas are given traction and action, they don’t come to fruition.

And there is uncertainty, there is ambiguity. A lot of times, they’re not linear and those creativity killers, “Oh, we tried that before. Oh, our customers wouldn’t go for that. That’s not in the budget.” Things are changing so fast that every one of those ideas that were killed last year, should be re-explored from a new perspective, and to ping ideas and grow ideas, and enhance ideas.

That’s where I love improv. This whole experience of improv where it’s “Yes, and” rather than, “No, but.” And “No, but” are end killers. “Yes, and” are enhancers, and allows ideas to ruminate, and nurture, and cultivate, and grow. And even if that only happens in brain storming session, being able to grow those ideas I think enlivens an organization; it enlivens cultures, it makes people laugh.

Come up with funny ideas, push envelopes. You know, be provocative with a purpose. That kind of expanding of our mind in a corporate setting is not only fun, but I think it can be very, very productive, and very profitable as well.

Roger Dooley: Yes, and we are just about out of time, Erik. Let me remind our listeners, we are speaking with Erik Wahl. His new book is “The Spark and the Grind: Ignite the Power of Disciplined Creativity.” Erik, how can people find you and your content online?

Erik Wahl: My website is TheArtofVision.com, my name is Erik Wahl, I’m on social media in all of those platforms that I’m learning the game just like everyone else, and I’m exploring, and trying to figure it out. If anybody else is on social … You know, first of all, thank you. If you’re listening this far into the podcast, I’m really, sincerely grateful that you’ve done that, and look me up.

Send me a note on social media, I’d love to stay in contact so this isn’t just a one-off. Let’s continue the dialogue; tell me how things work for you, what’s going on with your kids, in your business? Keep sharing ideas, I love the fact that that is part of our social media culture today. I encourage people today to reach out to me, to you; let’s continue this conversation.

Roger Dooley: Great. And I will also add that Erik Wahl is E-R-I-K W-A-H-L, because of those could be spelled different ways and we will have links to Erik’s website and social profiles and so on, on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast. We’ll also have links to any resources we mentioned during the show, and there will be a handy text version of this conversation there too if reading is your thing instead of listening. Although if you got this far, I guess listening would be the thing. Erik, thanks so much for being on the show.

Erik Wahl: Roger, thank you so much. I know there’s so many authors that would love to be on this podcast, and you chose me, and I just wanted to tell you personally how deeply grateful I am that you took the time and are willing to share this with your valued audience.

Roger Dooley: Well, it’s been a great conversation, Erik. We’ll have to have you back again.

Erik Wahl: I look forward to it.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.