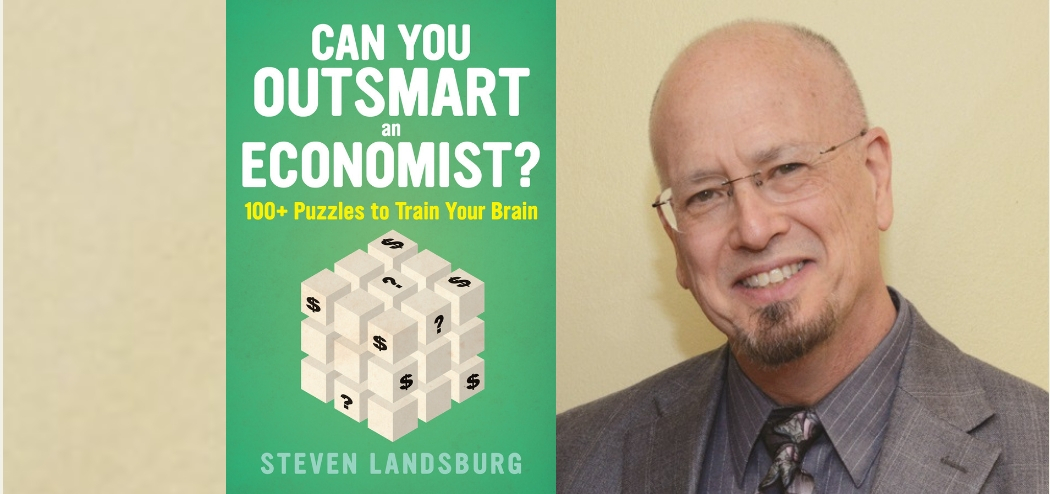

Steven E. Landsburg is a Professor of Economics and the University of Rochester and the man behind the popular “Everyday Economics” column in Slate magazine. Also the author of More Sex Is Safer Sex, The Big Questions, Can You Outsmart an Economist?, and the bestselling The Armchair Economist, Steven has written over thirty journal articles in mathematics, economics, and philosophy. His work has been featured in Forbes, the Wall Street Journal, and other publications.

Steven E. Landsburg is a Professor of Economics and the University of Rochester and the man behind the popular “Everyday Economics” column in Slate magazine. Also the author of More Sex Is Safer Sex, The Big Questions, Can You Outsmart an Economist?, and the bestselling The Armchair Economist, Steven has written over thirty journal articles in mathematics, economics, and philosophy. His work has been featured in Forbes, the Wall Street Journal, and other publications.

In this episode, Steven breaks down the surprising realities behind economic and social phenomena. Listen in to hear how height and pay are correlated, why we should all be grateful for people who hoard money, and why more sex is safer sex.

Learn the surprising realities behind economic and social phenomena with @stevenlandsburg, author of CAN YOU OUTSMART AN ECONOMIST? #economics #braingames #problemsolving Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The complicated reason movie popcorn is expensive.

- Why those who hoard money are the most socially beneficial people.

- The problem with taxes.

- Why it’s likely that better-looking teachers are truly better teachers.

- Steven’s take on the environmental debate.

- The reason the world has too much pollution.

- Why manufacturers like Sony restrict distributors and retailers from selling at a discount—and why this is actually better for consumers.

- The fascinating correlation between height and pay.

- Why more sex is safer sex.

Key Resources for Steven E. Landsburg:

-

- Connect with Steven E. Landsburg: Website | Blog | Twitter

- Amazon: Can You Outsmart an Economist?

- Kindle: Can You Outsmart an Economist?

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley. Author, speaker, and educator on neural marketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is Steven Landsburg, a professor of economics at the University of Rochester. You might expect Steven’s books to be heavy tomes, full of jargon and complex equations. In fact, he’s the author of “More Sex Is Safer Sex.” A topic we’ll ask Steven Landsburg as we chat. He’s also the author of the bestselling, “The Armchair Economist.” His new book is, “Can You outsmart an Economist.” “100 Plus Puzzles to Train Your Brain.” Welcome to the show, Steven.

Steven E. Landsburg: Thank you.

Roger Dooley: Steven. Your book, the Armchair Economist, was a popular success because it looks at everyday issues and explains them from an economist viewpoint, in often a viewpoint that’s counterintuitive. The famous economists, Milton Friedman called it ingenious, which I would say it’s high praise indeed.

When I was looking at the books, Amazon listing, I found one puzzle that I’m not sure economics can answer. The ebook is $13, the paperback is $15 and the hardcover primary listing was $972. But if you click the other seller’s link, then you can find new copies for $44. Is there an economic explanation for that?

Steven E. Landsburg: You would have to ask the folks at Amazon about that one. I’m often struck by those 900, $1200 prices that I sometimes see for books on Amazon, and my experience is that usually if you click on those, they’re not available at all.

Roger Dooley: Well actually they warned me that there was only one copy left at that price, so.

Steven E. Landsburg: They don’t tell you that there are copies of the other?

Roger Dooley: Right? Yes. You might do. If you’ve got any copies sitting on your shelf gathering dust, maybe undercutting by $5, turn a pretty good profit on that. I think that sometimes those prices result from algorithmic bidding. Somebody is set to bid a dollar more than the other lowest price, and they get into … Two computers start arguing and they get into a bidding spiral, but in this case I didn’t really see evidence of that.

So I have no idea what’s going on, but I thought that was rather interesting economics conundrum, that that hardcover would be worth $970.

Steven E. Landsburg: My sister was a big seller on Amazon. I bet she might have some insight into this. I’ll ask her when I talk to her.

Roger Dooley: Right. She might want to jump on that right now. It could be an opportunity. In that book Steven, you explain why movie popcorn is expensive, which probably most people who’re listening are saying, “Well Duh!” But why use movie popcorn expensive?

Steven E. Landsburg: Well, this is a good example … As a good example of the kind of thing I’m trying to do in my new book, “Can You Outsmart an Economists.” A lot of things have answers that appear to be obvious and yet when you think a little more deeply, the obvious answer is wrong. On the movie popcorn, people say … Well, it’s obvious, you go into the movie theater, once you’re in there, the theater owner has a monopoly on the popcorn, so of course he’s going to charge you a monopoly price for it.

That explanation founders on the fact, that if you know that he’s going to exploit that monopoly power, you are less likely to show up at the theater in the first place, and he’s going to have to give you a discount at the box office in order to get you in. So it’s not clear he’s gaining anything from this.

And if you’d like to make that … If you’d like to see that a little more graphically, notice that once you walk into the theater, the popcorn is not the only thing he has a monopoly on. If he wants, he could charge you $2 for the privilege of walking across the lobby because he’s got a monopoly on that, and another dollar for the privilege of walking through the double doors, and another dollar for the privilege of taking a seat, and another dollar for the privilege of using the bathroom. He’s got monopolies on all those things.

Why doesn’t he want to exploit that monopoly power? Because if he tried to, nobody would want to go to his theater, or it … The only way to get them to go to the theater would be to knock the box office prices down so far that he’d be losing, not winning. The question then is, why is popcorn different? That turns out you’ve chosen one of the more difficult puzzles in both books.

The answer to that turns out to be fairly complicated and got to have something to do with the fact, that the people who like popcorn for some reason are also the people who are willing to spend a little more money, and so you’re trying to extract more money from the people who are willing to spend more money, and it turns out as a statistical fact, that the people who are willing to spend more money tend to be people who like popcorn, and this is a way of extracting money from them without extracting money from the other people who would be driven away by that attempt.

It’s much more complicated than it looks. And once again, the real lesson there is not about popcorn or movies. The real lesson is that what’s obvious is not always true.

Roger Dooley: Yes. That’s an underlying theme across your writing. It seems like Steven. Well, okay. In that same book you’re talking about why taxes are bad and I’m sure folks who are listening have their own political explanations for why taxes are good or bad, but what’s your explanation?

Steven E. Landsburg: Well, the problem with taxes keep people … Again the obvious thing is; taxes are bad because they take money out of my pocket. But that is offset by the fact that the taxes that come out of your pocket go into somebody else’s pocket, and the taxes that come out of other people’s pockets, go into your pocket.

So the fact that taxes are taking money out of your pocket is not what’s bad about them. What’s bad about them is that people take costly measures to avoid taxes. And those costly measures don’t benefit anyone. Among those costly measures, they simply cut back on their activity. They cut back the size of their business, they cut back the number of hours they work, they … In other words … And we all know this of course, that taxes create disincentive effects and those disincentive effects are a bad thing.

The point here is that that’s really the thing to focus on. And People who grumble, “I don’t like taxes because I don’t like paying them” Are missing the point, the reason not to like taxes. And of course that doesn’t mean we should never have any taxes. But if we’re making our list of pros and cons on policies, what’s going to go in the con list on any taxes that it retards activity, that it incentivizes people to work less, it incentivizes people to produce less.

Roger Dooley: That’s … Currently working on a project about friction and the taxes are a form of friction. A little bit different than what economists call frictions, but no a lot of overlap there. And one of the things that I’ve noticed is that, people who pass legislation to increase or decrease taxes, are readily acknowledged that taxes can decrease undesirable behaviors.

Like we’re going to put a tax on tobacco with the effect not only of raising revenue but also to curb consumption. But those same people, if they were passing a tax on income, would typically not acknowledged the fact that people will somehow, and not everybody, but there will be an overall tendency to reduce income somehow, whether it’s working less, whether it’s hiding income, working in an undocumented way, but there will be an effect on behavior regardless.

Steven E. Landsburg: What a great point regarding the inconsistency of people who on the one hand say that we can retard smoking or retard people from throwing away aluminum cans by taxing them and yet at the same time are quick to overlook the fact that any tax is going to cause people to stop doing something.

Roger Dooley: I mean, it changes behavior, and it depends too if it’s a reasonable tax that isn’t noticed much. Should probably be effects on behavior be minimal. If it’s really high, then people will go to great lengths. In fact the state of Florida has a huge population of professional athletes, which is part … Is probably due to their great climate.

It’s warm all year, so you can practice your sport if it’s an outdoor sport, but also there’s no state income tax so that those athletes who spend much of their time in Florida save quite a bit of money, and then in that case all they’re doing is changing their residents, they’re still playing their sport, earning their income.

But in that case their behavior was changed to relocate, their legal residents. So one last question about the underground … Sorry, not the under … The armchair economist. We did speak to Tim Hartford earlier, which actually he is the undercover economist, although not only did I make that mistake when I was chatting with him, apparently I think was the Guardian made that mistake when the reviewed his book too.

It is strange, but in any case, you close the book with talking about environmentalism being like religion, and … This … The book was written a while ago and perhaps your feelings have evolved, but I’ve always felt that it’s a religion because people change their behavior to create some greater benefit were in fact the effect of that behavior change that they’re doing, say, buying a small very economical car, or going to great lengths to carefully recycle every product that they buy.

That really won’t affect the globe or the planet at all. It’s infinitesimal, but they still behave in that way and it’s … To me that makes them more like a religion, and religion is not all bad if it makes people behave in a pro social way. If it keeps you from killing your neighbor, stealing your neighbor stuff, religion is good in that respect. What’s your take on that?

Steven E. Landsburg: This was not exactly the point I was trying to make.

Roger Dooley: No. That’s just my analogy.

Steven E. Landsburg: But my concern with debates about environmentalism is that different people have different priorities. And some people would prefer to see more development and some people would prefer to see less, and there are all kinds of reasons for these things. And we ought to be able to recognize that we have differences, and argue about those differences, and recognize that it’s okay for different people to want different things.

And it’s annoying when people want things that are in conflict with the things that you want, but that doesn’t make them bad people. And what I see particularly on one side of the environmental debate, is a confusion between costs and sins. If I want to build an apartment building that’s going to displace some wildlife, that’s a cost. And that’s a cost that you want to take into account.

But the fact that I want to do that doesn’t make me a bad person anymore than the fact that you don’t want me to build my apartment building makes you a bad person. The whole lesson of economics I think, is that different people want different things, and we need to find ways of settling those differences. And we need to find ways of settling those differences without calling each other evil, and without turning economic questions into moral ones when there’s really no fundamental moral difference between the two sides. They’re just people with different priorities.

Roger Dooley: That’s fair enough. Moving onto your new book, “Can You Outsmart an Economist.” My initial answer, I guess is no. I couldn’t at least … As I started reading through the puzzles, I just tried quickly using my intuition to solve them, which proved not to be a great strategy. I found that my intuition more often than not was wrong.

One for example asks; what the probability is that two children are boys? In one condition you say that one is known to be a boy, and in the other one you say that one is known to be the Greek poet Homer. Now my quick answer was, it doesn’t matter if the boy is Homer or Franker or George, who cares? But you would say that my intuition misled me. Right?

Steven E. Landsburg: I would say that your intuition misled you. And I would encourage your listeners to buy the book and see why. Given we take two families at random, I tell you that one of them … Or we take a family at random, but two child family at random rather, I tell you that one of the children is a boy, I ask you, what’s the probability they are both boys? I tell you that one of the children is the blind poet Homer, and I asked you what’s the probability they’re both boys?

Those questions have different answers, and again, I’m going to encourage your readers to … Now if I tell you that one of them is a boy born on a Thursday, that question is going to have yet another different answer. I’ll encourage your readers to pick up the book and see why

Roger Dooley: Have we leave in hanging? Okay. Well, here’s maybe something else that you could explain is why manufacturers like Sony restrict their customers who are distributors or retailers from selling at a discount. Again, intuitively say, “Well, Hey” If you can … If they’re getting paid the same price and if their sellers can move more product to that way, then it’s a good thing. But … What’s your explanation?

Steven E. Landsburg: This is a great example of something where the obvious is the enemy of the true. I recently bought a Sony television and I shopped around for it and everybody’s charging exactly the same price. And the reason everybody’s charging exactly the same price, is because Sony insists that they all charge the same price or they won’t supply television to them.

Roger Dooley: Right? And as a consumer, I find that really frustrating when I have that experience.

Steven E. Landsburg: why do they care? A very naive person might say, well, they’re trying to keep up the price of their televisions, but when you think about it, that doesn’t make sense because Sony doesn’t care about the retail price of the television. They care about the wholesale price, and they control the wholesale price.

You just took this a step further and said … And you made the right criticism of that argument. You said, “Look, if the retailer can sell more product that way, that’s more business for Sony.” Sony’s going to set their wholesale price. If they get more business at that price, that’s great.

So why would they not allow a discounter to sell me a television set for 80 percent off? Well, it turns out that the reason for that, is that what Sony is very worried about, is that if best buy sells me a television set for $3000, and there’s a discount or next door who selling the same set for $2000, I’m going to go into best buy.

I’m going to talk to the salesperson. I’m going to get all the information. I’m going to get them to show me the different sets. I’m going to get them to explain to me all the options. I’m going to get them to tell me … Give me an education about television sets, and then I’m going to go next door and buy the $2000 television set.

And that’s going to happen so often that Sony is … The best buy is going to say we don’t want to carry these Sonys anymore. So they are requiring the discounter to charge the same price as Sony in order to protect Sony so that Sony will be willing to continue to sell their products.

Now from the consumer’s point of view, that’s good and it’s bad. It’s good, because it means that Sony … The best buy is still carrying Sony, and best buy is still willing to answer my questions, and I can still go into best buy. I can go in there today and get a lot of help buying a television set.

What’s bad is of course I can’t find the television set at a discount. You could ask on balance, our consumers made better or worse off by this. And the answer to that takes a little bit more deep thinking than I think we can do on the radio, but it turns out that on balance consumers are better off. Consumers are paying more for their television set, but they’re also getting more service and the service they’re getting is in the minds of the consumers worth the extra price that they’re paying. Although they’re not always entirely conscious of that.

Roger Dooley: Yes. I know that’s been an issue for years. I was in the electronics business for a while in the early days of the computer industry, and there was a lot of debate about that because some manufacturers try to control the prices and others didn’t really care as long they bought their stuff, and one workaround a few manufacturers used was to sell the discounter the same product, and it slap or refurbish label on it.

So when the discounter would sell it at a cheaper price than best buy, and best buy went back to manufacturer and said, “Hey, this guy’s killing me on next door.” They’d say, “Oh, well, those were refurbished product. So it’s not the same as what you’ve got.”

Seemed to work some of the time. Everybody was more or less happy because the people who really wanted that full service, high conference environment when would pay the full price for it. Folks were a little more price sensitive, and might have even purchased another brand, could get it at the discounter.

But yes … Now there’s some ways to work around everything and seems … Now another strange … A little topic in the puzzle book is Scrooge Mcduck. And I think that probably most of our listeners know who’s Scrooge Mcduck is, but just in case, he is Donald Duck’s wealthy uncle, who is often portrayed sitting in his vault on a huge pile of money. So what that … Tell me a little bit about your take on Scrooge?

Steven E. Landsburg: Well, the question in the book, the puzzle I pose to the reader in the book is “Would we all be better off if Scrooge keeps all his money in a vault and he keeps all his money in a vault in cash so that he can bathe in it?” And the question I pose in the book is, “Wouldn’t we all be better off if he took some of that money and spent it and spread the wealth around?” The answer to that, and of course this is a question about a cartoon duck, but it goes to a lot of important issues in economic policy that people get wrong all the time.

The answer is of course not. If somebody is willing to hold a lot of cash, that’s the best neighbor you can possibly imagine because he is producing things in order to earn that cash and he’s not exchanging the cash for goods. Which means he’s producing more goods than he’s consuming, and that’s the best kind of neighbor to have.

As soon as he starts spending that cash, then he’s going to … If he buys a turkey, there’s one less turkey for everybody else to eat. If he buys a mansion, there’s one less mansion for somebody else to live in. The person who wants to hoard money, is again the very most socially beneficial neighbor that you could possibly have, and I think getting that wrong leads people to make a lot of mistakes when they think about important issues in economic policy.

Roger Dooley: Well, speaking of important issues, I don’t know if what you’re rating on Rate My Professor is, but you’ve looked at weather better looking professors actually are higher rated.

Steven E. Landsburg: This is part of a general theme.

Roger Dooley: Higher rated for their teaching and so on. Not necessarily just on an appearance rating.

Steven E. Landsburg: Better looking teachers get better teaching evaluations. There’s no question about it consistently. Now this is part of a theme in “Can You Outsmart an Economists.” You take a statistical fact like that, and you ask what does it mean? The obvious explanation is that students are shallow, students are swayed by physical appearance, and you have two teachers, and they’re the exactly the same quality, but one of them looks better, the students rate him higher, or rate her higher.

I don’t think that’s true. I think what’s really going on, is that better looking teachers really are better teachers on average. And the reason for that, is that good looking people have a lot of career opportunities that other people don’t have. They’re more in demand in retail, they have career opportunities to be models, to be actors, to be actresses.

The good looking people, with all of those options who chose to teach, must be people who are really enthusiastic about teaching. The other people who went into teaching, even though they weren’t attractive, maybe they went into teaching because they just had no other options. They’re going to be less enthusiastic. They’re probably going to be less good teachers.

As I say in the book, if you show me a lighthouse keeper with movie star good looks, chances are you’re showing you the best light housekeeper in the world, because if you’ve got movie star good looks, you don’t have to be a lighthouse keeper, and if you chose to be one, it’s probably because you really love light housekeeping.

So there’s a good example I think of how a little statistical fact points in a direction that looks obvious but really is not true.

Roger Dooley: Well, do you think then that explains the research that shows that people in business get promoted more when they’re better looking is … Because you get advanced that same argument there, right? Not that somehow there’s this halo effect that they’re better looking so they get promoted even if they’re only equally competent. You could use the same argument, right?

Steven E. Landsburg: That some of it, but when you go to business, there is also another very interesting fact, which is that there is this big premium for beauty. There is also a big premium for height, which is presumably the same phenomenon. So people who are taller on average … If you’re an inch taller than your neighbor, and you’re equally good at your job, on average you’ll be earning about a $1000 a year older than him. If you’re a foot taller, $12000 a year. So that’s pretty substantial.

But the really interesting fact, and I talk about this in one of my books, is that if you look at tall people who were short for their age in high school, they tend to earn like short people. And if you look at short people who were tall for their age in middle school, but then stopped growing, they tend to earn like tall people. So that suggests that the premium for height has nothing to do with how tall you are right now. It has to do with how tall you were when you were in high school or middle school, forming yourself image, learning how to think about yourself and learning how to interact with other people.

Roger Dooley: That’s really fascinating. So do you think it’s … This isn’t shown by the data, but what do you think causes that? Are they … These people more confident, more dominant?

Steven E. Landsburg: That would be the obvious guess now. A big theme in all my books is don’t just jump on the most obvious guess, but in this particular case, that’s the best guest I’ve got. You might say, “Well they earn more because they’re taller and therefore they intimidate people.” But that explanation doesn’t work once you realize that your height makes no difference to your wages, unless you were already tall when you were 16.

So some sense of confidence. Some sense of thinking of yourself as a natural leader, seems … Is … It’s the best explanation I’ve got. I will be thrilled if somebody finds a better one.

Roger Dooley: Right. It could be an argument perhaps for holding a child back a year. And that’s true in sports as well. And that there’s been research on that showing that, success in sports depends on when one’s birthday is, and whether you’re the oldest in the class or the youngest in the class. So you had another argument for them?

Steven E. Landsburg: But of course they … That goes to another set of issues which is that, I think it’s great to try to give your kid skills that that kid can use to make the world a better place and benefit from making the world a better place. And produce better products and therefore earn higher profits, I’m all for that.

But when … What you’re talking about is not quite in that category, it’s holding your kid back so that your kid can do better so that some other kid can do worse. Because in athletics there can only be one captain of the team. There can only be one winning team in any game. So it’s more of a … Here you’re talking more of a zero sum kind of thing.

Now, from your personal point of view, from what is to your advantage, from what is … From the point of view of what’s to your kids advantage, yes, it could very well make sense to hold your kid back. But I still hate to see people doing it, because in doing it they’re just hurting other people’s kids.

Roger Dooley: Well, yes. And it’s sort of thing that you can optimize for yourself, for your offspring, but that is not going to be necessarily optimizing for the world or everybody else.

Steven E. Landsburg: That’s exactly right. And I think that’s true of a lot of competition. I mean I … Competition is the greatest force that we have for progress, for getting people to make the world a better place in so many ways, but you have to be careful because not all competition works that way. Some competition is zero sum. Some competition is just arms races, people trying to stay ahead of each other and nobody really getting ahead. And so there are … Much competition is great, but some competition is not so great.

Roger Dooley: Okay. Before I forget, at the beginning we teased a really important question that I know everybody wants to hear the answer to. Why is more sex safer sex?

Steven E. Landsburg: Well, again, another case where the obvious is perhaps the enemy of the true. Let me start just by saying a couple words about pollution, where the obvious is exactly what’s true. The reason the world has too much pollution, is that polluters don’t always bear all of the costs of their actions. I put … Pollution comes out of my smoke stack and other people have to read that and I don’t care about that, so I over pollute.

And by the same token, people do not go out and clean up the parks voluntarily as much as we would like to see them doing. And the reason they don’t do that is because the benefits of that are largely grabbed by people other than themselves. And when other people bear costs of your actions, you do too much of them. When other people benefit from your actions, you do too little of them.

All of that I think is easy to grasp and not controversial. When you apply that to sex … Let’s imagine for a moment that you, and when I say you, I’m talking about some generic you. I want to make clear, I’m not talking about you personally.

But let’s suppose that you are a very promiscuous, reckless person who’s had a lot of partners and are therefore likely to be carrying terrible diseases. Every time you go out and find a new partner, you are making the world a less safe place. It’s exactly like pollution. The partner that you go home with is taking a risk that the partner is not even aware of because they don’t know about your past behavior. They don’t know about your riskiness. It’s just like pollution. You are making the world a worse place, and it would be a good thing if we could find a way to find people like you, to have fewer partners.

Again, seems pretty obvious, seems pretty uncontroversial. But now let’s look at the flip side of that. The flip side of that, is that if you are an unusually safe person, and you know yourself to be completely disease free, every time you go out and find a new partner, you making the world a safer place, because the person who goes home with you, you just saved that person from a prospect at least for one night of going home with somebody riskier.

Every time you go out and have another partner, you are slowing down the spread of disease because you were making it harder for the promiscuous people to find partners. And so the world would actually be a better and a safer place, if we could get all of the very safe people, to have more partners.

Now we don’t want them to have too many more partners or they’ll become just like the risky promiscuous people. But it turns out if you do some careful analysis, and use some insights from epidemiology, and some insights from economics and what we know about the way people respond to incentives, you could substantially slow down the spread of STDs, if you could take everybody with fewer than about three partners a year, and bring them up to three partners a year. Not much past that, but if you could bring everybody up to at least three partners a year, you would actually substantially slow down the spread of STDs.

Roger Dooley: Well, there is a lesson that we have not had on this show before. We’ll let our listeners do with that information what they will, but fascinating stuff.

Steven E. Landsburg: I explained in the book, not only … First of all, I elaborate on that argument. Second of all, there’s actually a second reason why it would be good for those people to have more partners. The second reason is even more important but a little harder to explain in a short podcast. So that’s in the book. And then finally the lessons that we learn from these non obvious and surprising discussions. These non obvious and surprising analysis turn out to apply not just to sex, but to many many areas of economics. So we can have the fun of thinking about sex, and then get the payoff at the end that we actually understand some economics.

Roger Dooley: Now that’s lesson that probably students would enjoy hearing and not the same old macro and micro lecture. One last question; do you try out some of these puzzles on your fellow economists? And do they always get them right? Or have you found that economist can be fooled by these things too?

Steven E. Landsburg: Sometimes economists are fooled by them. Sometimes of course students are fooled by them. Some of them have appeared on my exams. And sometimes I’m fooled by them. There’s not been … There’s been more than one occasion where I’ve come into the coffee room with what I thought was a very clever new puzzle and presented it to my colleagues and they gave me an answer I didn’t expect and I ended up realizing that they were right and I was wrong.

And I said my colleagues, but I should also acknowledge my blog readers. I have a blog @thebigquestions.com where I have been blessed with an incredibly brilliant and clever bunch of commenters. I don’t know where they all came from. But many of the puzzles in Can You Outsmart an Economist first appeared on my blog, and were vetted by my blog commenters, and torn apart, and many of the puzzles were dramatically improved by the discussion that took place on my blog. I learned a lot of things about them myself for my commenters and I’m thankful for them every day.

Roger Dooley: Wisdom of the crowd. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking to Steven Landsburg, economist and author of, “Can You Outsmart an Economist.” Steven, where can people find you and your ideas online?

Steven E. Landsburg: Online for the book, for the Puzzle Book, outsmartandeconomist.com. That’s all one word. outsmartandeconomist.com for my blog. thebigquestions.com.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to those places and to any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast, and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Steven, thanks for being on the show.

Steven E. Landsburg: Hey, thanks so much for having me.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.