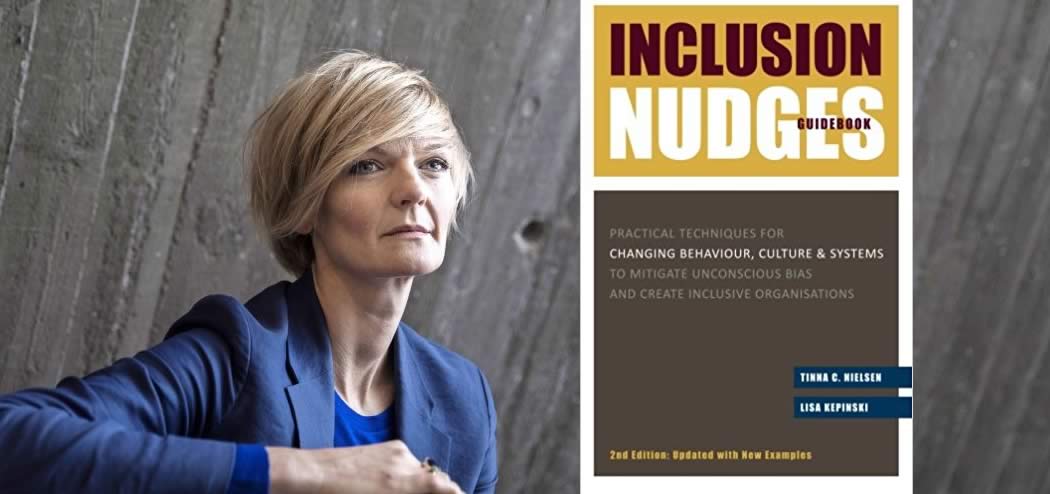

Today’s guest has made it her mission to use behavioral science to improve inclusion and diversity. A behavioral economist and expert in organizational change, Tinna Nielsen is the founder of the non-profit change-organization Move the Elephant for Inclusiveness, the co-founder of the non-profit Inclusion Nudges Initiative, and the co-author of the Inclusion Nudges Guidebook. She is also a strategic partner for inclusiveness and gender parity at the United Nations, and Tinna collaborates with organizations, practitioners, and social entrepreneurs worldwide to redesign communities and organizations.

Today’s guest has made it her mission to use behavioral science to improve inclusion and diversity. A behavioral economist and expert in organizational change, Tinna Nielsen is the founder of the non-profit change-organization Move the Elephant for Inclusiveness, the co-founder of the non-profit Inclusion Nudges Initiative, and the co-author of the Inclusion Nudges Guidebook. She is also a strategic partner for inclusiveness and gender parity at the United Nations, and Tinna collaborates with organizations, practitioners, and social entrepreneurs worldwide to redesign communities and organizations.

In this episode, Tinna shares the surprising truth about the unconscious snap judgments we all make, as well as the devastating experience that led to her realization of what it really takes to influence people to change their behavior. Listen in to learn what types of unconscious biases we all have, as well as how to prevent those biases from affecting our communities.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Two traits we all unconsciously rate people on.

- The truth about how reliable our perceptions are.

- How a simple change in wording can greatly reduce gender disparity.

- The problem with job interviews.

- How to fight conformity.

- The huge societal cost of exclusion.

- Why using facts to change behavior doesn’t work—and what to do instead.

Key Resources for Tinna Nielsen:

-

- Connect with Tinna Nielsen: Twitter | LinkedIn

- Amazon: Inclusion Nudges Guidebook: Practical Techniques for Changing Behaviour, Culture & Systems

- Tinna’s TEDx Talk: YouTube | LinkedIn

- Inclusion Nudges

- Move the Elephant for Inclusiveness

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Announcer: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is Tinna Nielsen. She’s a behavioral economist who’s an expert in organizational change. Her focus for years has been on using the tools of behavioral science to improve inclusion and diversity. Tinna is founder of the non-profit change organization, Move the Elephant for Inclusiveness and co-founder of the non-profit Global Inclusion Nudges Initiative.

Prior to that, she worked as Global Head of Inclusion and Diversity in a multi national corporation and at the Danish Institute for Human Rights. The World Economic Forum honored Tinna as a young global leader, and she is now co-chair of the Global Future Council for Behavioral Science at the World Economic Forum. And Tinna is the co-author of the Inclusion Nudges Guidebook. Welcome to the show, Tinna.

Tinna Nielsen: Thank you very much.

Roger: Well, Tinna, what caught my attention first about you, I think, was the name of your organization, Move the Elephant. That’s kind of an obscure reference, but it’s one familiar, probably, to quite a few behavioral scientists. I first ran across it in Chip and Dan Heath’s book Switch. Why don’t you explain the origin of the Move the Elephant name?

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, so I have worked with human behavior for many, many years and all my career, basically, and it’s fair to say that I know a lot about human behavior and my background is anthropology and I obviously know a lot about what we do as human beings and what’s driving our behavior. I realized, after 10 years of working for creating more inclusive organizations and workplaces and communities that I might know a lot about it, but I wasn’t actually applying my knowledge in a way that … behavioral wise.

And then I came across the brain analogy, a psychologist, Johnathon Haidt, which is the one the these brothers are referencing as well and he was describing these two brain systems that I anticipate that the majority of the audience of this podcast know about, the system one and system two. The rational mind and you know conscious mind. And it wasn’t until I was reading about this brain analogy that the rational mind is like the writer on top of a six ton heavy elephant, which is the unconscious mind and the system doing about 90 to 99 percent of our behavior and decision making.

Literally that image made me wake up and I realized when I looked back, which was a scary thing to do, I looked back 10 years and realized that the majority of the time I had actually created interventions or done things to create these changes for more inclusive collaboration and decision making where I was appealing the majority of the time to the writer, to the rational mind. And the things that were actually working and had created sustainable changes was when I had not talked, I had not done anything to convince people. I had not used business cases to show data and why this was so important, I had literally appealed to the unconscious mind without language. And I found three different types of interventions that have been working throughout the years.

So based on identifying those three types of interventions, this is when I founded this non-profit organization I call Move the Elephant for Inclusiveness. Because I figured there was probably other people making the same mistake as me, knowing a lot but not actually applying that knowledge in a way that helped people, and made it easy for people to do what they had intentions to do or to make the changes that we needed.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, I love the elephant metaphor because it’s, it really sort of makes tangible the issues we face when we’re trying to change behavior and so often we are using those rational arguments aimed at the writer when the writer has very limited control over the elephant. There’s a great animation online, I’ll see if I can find it and post a link in the show notes. But, showing how it’s … if you want to get the elephant moving in a particular direction, the best thing you can do is make it easy for the elephant to move in that direction and not worry about trying to convince the writer to move that way.

Tinna Nielsen: Mm-hmm (affirmative). The reason why I think I … you know, the majority of things that happen in our lives is kind of like random or serendipity or it’s difficult to plan a lot of the things that happen in our lives. And I think the reason why my mind was actually open for that brain metaphor and things kind of fell into sync and breaks in the puzzle kind of started matching and fitting into this bigger picture was because just a couple of weeks before I came across this brain analogy, I had had a horrible experience with the executive team in the multinational company where I was working.

The CEO and I were attending at ten year strategy for how to create system-wide cultural change in this organization to actually create inclusiveness in a way where it’s not about minorities or helping women get to the top of the organization, but it was a much broader concept where it was about, how do we actually innovate better if everybody is able and have the ability to listen and tap into a diversity of perspectives and actually apply it in the way we collaborate and discuss and problem solve and make decisions. And how do we mitigate bias in all the organizational processes so that we make better decisions and so forth.

So that, there was like a huge organizational development process. So it was a ten year strategy. I had been given 45 minutes to present this to the executives. I had prepared so well, I had all the data ready, it was like, great. And I think about 15 minutes into the meeting, the CEO stops me and he goes, “You know, just stop. I don’t want to hear anything more.” I’m like, in total panic, and he’s like, he says to me … I’m grateful for it today but at the time it was absolutely horrible.

He says to me, “You know, this is just too complex. I mean, we don’t understand this intellectual, I mean, it doesn’t make sense.” And I was just thinking to myself, “Oh my god, I did such a great job using complexity, you know, as in anthropology we open up complexity, open up, open up,” and I’d really done a big piece of work to reduce it, made it simple, like a lot of one pager statements like that.

And he said, “We just don’t understand this.” And he looked at me, he said, “You know, we believe in this with our hearts. Your job is to get us moving. The ten of us in here, we’re ready to run, get 15,000 other people moving the same direction we all have to go, just don’t talk to us about it.” And I was like, you didn’t say that! I’m like, looking at the others like is this a joke? And nobody … everybody’s looking down, because this is obviously very embarrassing.

I pack up my stuff and I’m on the way out of the executive team meeting room and I turn around the door and I say, “Listen, I just need to understand my mandate.” I mean, it’s not like I had anything to lost at the time, right? So might as well just ..l so I’m like, “I just need to understand my mandate, you want me to get 15,000 people moving, but you don’t want me to tell them where they’re going or why they have to move there?” And he’s like, “No.” I was like, “Wow. It can take a long time before they meet then.” He’s like, “Well, it’s okay. culture changes take time.”

So leaving the room, I was devastated. I spent weeks licking my wounds. I felt so incompetent. And when I came across this brain analogy, it just kind of made sense because what that’s showing is the rider is the brain, right? The intellect? And that’s what he said, “Don’t talk to that. Appeal to our hearts and get us moving.” Which is the elephant.

So it’s like, I don’t think that if I hadn’t had that horrible experience where he had said that, that this rider-elephant metaphor had made so great sense to me. So for me it also became like a mantra, like a pledge to myself where I said to myself, “I will never again present one more business case on this. Because it doesn’t make a difference.” And actually to this day, since 2011, I have not presented on single business case, and I’ve never seen as many changes as I see now in the organizations where I work.

And so the pledge was, our foremost focus is on appealing to that elephant. And also a statement of mine became, if you want gender equality stop talking about gender equality. If you want more diverse organizations, stop talking about diversity. You know. So that’s actually what I’ve been doing since.

Roger: Right, well I think that’s a great example where here you are, a behavior specialist and sort of do what many of us do and that is say, “Well, yeah I know this is how humans behave, but I’ve got to convince these executives of what to do,” and used a very rational system two type approach.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah! Mm-hmm (affirmative). But you know, this is what happens all the time. Because we are really just trying to fit into the system a lot of times, right? Which is what we know from when you hire in a new person into a system or an organization, it takes about six months until they’re socialized into being like everybody else. Socialized into fitting into the norms. Because that’s what we do as human beings. We really, really, really have a basic need to fit in. So I did the same. I was the only anthropologist in this manufacturing company. They’d never seen such a person, they never heard such a language. I did whatever I could.

So they asked for a business case, they asked for a one pager, asked … that’s what they got. But that’s where, you know, it dawned on me. Probably not the best approach if we actually want some changes. So I think, actually, the major failure made me dare to stand by what I know, which I think I had forgotten in trying to fit in! I mean, yeah, so.

Roger: Right, well that’s a good lesson for those folks out there that sometimes, you know, having a sly deck full of data is not the way to communicate, even with smart people who probably could understand the data, but that isn’t necessarily what they wanna hear.

So let me change gears for a second. You have a TEDx talk online on YouTube and other sites. It starts off with an audience participation thing where you show folks a couple of pictures and unfortunately this is an audio medium, so we cannot show our listeners those photos. But I wonder if you can sort of do an audio only version of that test. Just sort of describe what the audience saw and what they chose, both in the TEDx audience as well as when you’ve run that test elsewhere.

Because I think it’s really sort of a great stage setter for this entire topic. Not just inclusion and diversity, I mean those are important things, but really in many of the ways that we evaluate people, whether it’s trying to hire a coder, or a sales person, or whatever. Why don’t you just do the best you can to draw a mental picture of your photos and what the audience tends to do.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, yeah. See, this is a very interesting dilemma you’re putting me in, right? Because what the Inclusion Nudges techniques are about is about not talking to the intellectual mind and not telling, but showing. To get people to experience something or see something they’re blind to. So you’re gonna have to experience it for that elephant to be moved or touched or want to do anything. So that’s what that exercise is actually about, so now that you’re asking me to tell it, I’m…

Roger: No, that’s okay, I’ll set the stage. Here, how does this sound Tinna.

Tinna Nielsen: Why don’t we make it a cliffhanger, Roger?

Roger: Right, well.

Tinna Nielsen: Let’s make it into a cliffhanger and tell them, I’m showing two pictures. So I’m showing a picture of my husband and I’m showing a picture-

Roger: Well, no, that’s a spoiler though.

Tinna Nielsen: No, no, no, no, it’s not, yeah, because no, when people watch it, they’re gonna have to think about who’s who.

Roger: Right. Okay.

Tinna Nielsen: So I’m showing a picture of my husband and I’m showing a picture of a serial killer. And I’m asking people in a few seconds to rate them on two traits that us human beings always in a split second with the unconscious, instinctive mind, rate people or evaluate people on when we meet people or collaborate with them or have to hire them or listen to their idea when they’re pitching a suggestion. Or whatever we’re doing with people. These two traits are always something that we rate people on. It’s from a survival kind of mode, or state of mind, sorry.

And so we rate them on warmth, which is about trustworthiness and likeability and do we trust they wanna do us good and is it safe for me to be here, should I attack or should I get out of here? And then we rate people on competencies. Skills and authority and power, and do we believe that, you know, is it good for me to invest in doing anything with them. So we rate them on these two traits, and that’s what I’m asking the audience to do and it’s a very obvious pattern in what people are rating. And with one picture, the whole 800 people have their hands in the air, basically, high on warmth, high on competence, and with the other person, it’s really low on both.

Roger: Right, and the first person was a good looking young guy in a suit.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, exactly.

Roger: And clean cut, smiling, very pleasant looking guy like, you know, you might run into … not even at a car dealership, he looked even a little more ethical than a car salesman! And then the other fellow is sort of a frowning guy with no hair and a big beard.

Tinna Nielsen: But you know what’s funny with the first picture, the person that’s looking really nice and yeah, clean cut, as you say. Have you noticed the similarity to J F Kennedy and … in France and the famous … in Austria right now, and …

Roger: I did, but I hope you’re not right.

Tinna Nielsen: No, I’m not kidding you!

Roger: No, but you’re right.

Tinna Nielsen: There’s these really strong assumptions. So there is that person. Obviously I chose that picture based on that majority of brains worldwide regardless of culture and nationality or age, people rate people looking like that high and low.

Roger: Well there is a charisma in that face.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, yeah, yeah. But that’s it. The brain automatically, you know, picks up, “That person is a competent person. This is a nice person, a pleasant person. It’s a leader, it’s somebody we dare to follow because it makes us feel safe, that person obviously has some authority, let’s … ” you know, yeah. Good. It feels good, safe. So what I’m illustrating with that is that even though we believe that we’re open minded and we’re open to diversity and we make good and fair and sound decisions about competences and people’s skills and ability and we of course would choose the best idea over a bad idea, we would choose the best candidate over a less competent candidate, but it turns out we don’t exactly do that.

We actually also, even though we consider ourselves as open minded and so forth, we are all as biased as everybody else. We tend to jump to these fast conclusions and this is really influencing how we innovate and how we make decisions and who we hire, how we compose our teams or what stakeholders we prefer to work with, if we are an independent entrepreneur or … and what I’m illustrating, really, in that talk is it has some really, really huge consequences.

Roger: Right, well just the fact that the serial killer Ted Bundy looked like a totally trustworthy, friendly person and your husband the scientist looked, you know, maybe a little bit more threatening, perhaps. A little more unconventional. You know, that shows how unreliable our perceptions are. But at the same time, I would guess if you talk to a hundred managers and ask them what the most important part of the hiring process is, they would say the interview.

Because they feel that somehow, when they talk to this person and they see them up close and they see their face and so on, and their mannerisms, that they’ll be able to judge whether this person will be a competent coder or manager or customer service rep or whatever their job is. But … yeah, I mean the data, as I’m sure you’ve seen too, the data shows that job interviews are the least effective way of choosing candidates and that a blind selection process from resumes tends to produce better results.

Tinna Nielsen: Mm-hmm (affirmative), exactly. That picture exercise that I’m doing in that TED Talk is a very, very short version of a longer exercise that my very good friend and mentor, Howard Russ from Cook Russ developed many, many, many years back, and he shared it with me and we worked together to create a version of that that we were using in the multinational company where I was working. And I further developed it to fit the organization. And I then later on further developed it by using my own husband, because I knew that that would create an even bigger eye opener for people, so that they wouldn’t forget this experience.

And that exercise, that’s … you know, and now I design many of these interventions. But that is what I call a feel the need … Inclusion Nudge. Because you can’t tell people they treat people unfair. You can’t tell people, “You make horrible decisions when you’re hiring people.” You can’t tell people, “You exclude good ideas.” Or, “You interrupt women 2.8 times more than you interrupt your male colleagues.” You can’t tell people that. That’s not going to make a difference. People are going to feel ashamed, they’re gonna feel attacked, or they’re gonna feel like they’re bad people, or they’re gonna feel like you’re stupid because obviously that’s not what they do.

So you’re not going to get anywhere with it. So what these kind of feel the need interventions are about is appealing to the elephant to show people something or motivate them to wanna change it. So they literally come up with the business case themselves, without you having to show them a whole page of slides, data.

So that intervention is really about … we use that to show them how they hire. Or it could also be that somebody said, “Come in and give us a business case about global mindset. We need more global mindset.” I would do that kind of intervention instead. So everybody would start out by thinking, we’re saying, stating, that they had high global mindset, they work in a global organization, they have global positions. Really, really good at this. Very open minded, very skilled at this and that. And then afterwards they would realize, “Wow, okay, this is crazy.” And they can also laugh at it. And they also had a shared language.

And then after having given them that eye-opener, which was hugely motivational in terms of, “Hey, we wanna change this. We don’t want this. We wanna do what our self perception is. We wanna do what we have intentions to do.” And then we would give them very practical ways to then actually turn that around, and that’s what we call a process. Inclusion Nudge. You’re nudging the unconscious mind to be inclusive, redesigning the processes that they’re in.

It could be a strategy process, it could be a hiring process, it could be a feedback process. It could be, you know, things that they already do or specific ways that they do it. You redesign it so that you mitigate the biases, so it’s not something that you have to choose you wanna do, it’s not an active choice. It’s something you just help the brain do.

Like, say the organ donation system in countries, you’re asking a citizen, “Do you want to donate your organs if you were to die?” And that’s a complex choice for people to make. But the majority of people will say, “Yeah.” But they don’t sign up in the system because of the complexity in doing such a thing. Whereas if you redesign the process and the system and you change the default and say, so in the countries where they do this, they say, “Hey, listen, we already signed you up. From birth, you’re signed up. But you have the freedom to opt out. We’re not asking you to opt in, because we already did that to you in accordance with the majority of people’s intentions. You’re free to choose to opt out.” That’s what you can do for inclusion and diversity as well.

So organizations are doing this, for example, say talent discussions, or discussions about who should get that promotion or that extra responsibility, or who should have a success…They meet up in a team of leaders and they discuss who’s ready and then they start looking for facts proving that that person they already pointed out is ready. That is a hugely biased process not going to give you the best qualified candidate.

Whereas when they flip it around and change the default and say, “Well, everybody in this pool is a candidate already. Now, let’s look for facts that proves that they’re not ready.” That forces the brain to start looking for something different, and not just go in the same biased homogenous pattern that we have always viewed people in. And also that you’re looking at the people compared to each other instead of compared to a stereotype of how you’re supposed to be. Because then we end up having all the people looking like Ted Bundy.

Roger: Right. Right, yeah. You know, I think a nudge of the kind you’re talking about, years ago symphony musician auditions for first chairs and what not were conducted in the open and you tended to have a lot of mostly male musicians getting the top positions at the top orchestras. And then they started doing them from behind a screen, and suddenly the number of women getting hired really increased for these key positions. And I doubt if most of the people who were conducting the auditions overtly felt, “No, we’ve got to have a guy in this position.”

Tinna Nielsen: No, of course not.

Roger: But I think it was much more that, “Well, gee, I know what the first chair for Chicago’s symphony looks like,” and so on.

Tinna Nielsen: Well yeah, it can’t just be, right?

Roger: And yeah, “So we want somebody like that.” In the same way that, you know, if you want a coder, “I know what Mark Zuckerberg looks like, so I need more people like him.”

Tinna Nielsen: And it’s not just how people look. We know that appearance has a huge impact, but, and I’m sure the audience knows this, you know, a name makes a huge difference. And we know this because there’s so many experiments being done now where you take the same job application, you send it to a lot of, you know, where you change the name and then they choose the man, or the one with the ethnic traditional name and so on.

But it’s interesting when we look at, for example, innovation and open innovation is really hip and happening. And we know we need this, because this is the only way we’re going to be able to innovate for a future that’s, you know, I mean, we can’t even imagine what’s about to hit us. But when there’s these open source programming platforms where people can share their codes, for example, for free, right? People share their codes and their project manager can then choose these codes for free and integrate it in their project. This is a great example of how we can innovate for the future.

But the problem is, if the project manager can see the name of the programmer, there’s a bias sneaking in again. Because if they can’t see it, it turns out that they at the same rate use male and women programmers. But actually some research has shown that they choose more female programmers code than men. But as soon as they can see the name of the programmer, it drops for the women programmers. They choose the males. Because in their mind, tech, engineering, you know-

Roger: Right, there’s definitely a stereotype there.

Tinna Nielsen: There’s a stereotype that that’s a male thing. And obviously you ask project managers like, “Why would you choose a code that’s not the best?” They will go like, “What are you talking about?” I mean, with the thousands of leaders worldwide I work with, I have never heard a leader say, “My finest job is to go into work and make sure I waste about 50 percent of my employees’ skills and abilities. I’m gonna make sure I hire the worst possible candidate just because they look like me, or the 90 percent of the staff we already have. I’m gonna definitely not choose the best idea in the pitch session today.” You know? I’ve never met anybody like that. So I think it’s fair to say that there’s something going on subconsciously and talking to people about it is not going to change it.

It’s not because we’re bad people, because that, you know, the size difference in the influence of what we do. And marketeers have done this for decades, and I’m sure a lot of the audience listening will go like, “What’s new in this? I’ve done this for years.” I think what’s new in this is add the things we’ve proven work in a lot of different domains. Like, we can get people to eat more fruit by making sure it’s next to the cash register, cash machine, in … what is it called, supermarket.

Roger: Cash register, right, yeah, mm-hmm (affirmative).

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, exactly.

Roger: Yeah, at the checkout, right.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, instead of the candy, right? I mean, you can serve the food on smaller plates and people eat less. And you know, these things. What’s new here is that I started applying all those examples and I took it into a context of people’s abilities. We can leverage people’s different perspectives and different knowledge much better, how we can mitigate biases that are obviously more harming than benefiting us. At the same time, knowing it’s a very natural thing to have, it’s what keeps us safe in traffic and what keeps us safe in many different situations. But there are also situations where those automatic, instinctive reactions are flawed.

And when we look at how different people are, we are seriously flawed in the sense that we are wasting human potential at a scale that we cannot afford. We never really could afford it, because there’s so many negative spinoffs here. Not only are we losing out on good ideas, losing out of the ability to be creative and innovate faster, make great decisions, but we are also hurting people. And we know there is a strong correlation to people feeling really disempowered and they feel ashamed that they’re not good enough, that they’re not strong enough, that they’re not man enough, they’re not woman enough, they’re not a good enough father, they’re not a good enough mother, they’re not a good enough friend, they’re not, you know, a good enough leader.

And all of that is really associated with the feeling of shame that “I’m not a good enough person.” And that has, like Renny Brown had proven in her research over the past, I think about 15 years, is that that leads to obesity and drug abuse and that we have fat sucked out of our butt and put in our cheekbones to be more pretty. That we beat each other up, that we put each other down, that we, you know … attack each other in our workplaces by putting each other down so I look better myself, which is not helping us. It’s just making us feel even more lousy.

We have sexual harassment, we have … suicide rates are going up in the western world among men in their forties because they don’t fit the masculinity norms anymore. It’s like the whole world is a mess. And it actually has a strong correlation to a lack of inclusiveness. That the default is exclusion. It has this huge societal cost, it has a huge business cost, it has huge health costs.

Roger: Well, there’s probably some human tendency towards exclusion that has to change. I think that when we were tribal societies, that was really a sort of survival element that you sort of bonded with the people who were like you and outsiders were shunned or avoided because they could be dangerous. I mean, you know, we carry those programs with us even though they may not be effective anymore for what we’re trying to do.

Tinna Nielsen: Mm-hmm (affirmative), absolutely.

Roger: Yeah, you know, one of your nudges talks about conformity and how to fit it. Now, you reference in passing in the book the Asch experiment, which probably a few of our listeners are familiar with that, but in any case, a subject goes into a room with five other subjects, or he or she thinks they’re subjects but actually they’re confederates of the experimenter. And they’re all asked a question like, “Which of these lines is the same length as this other line?” And there’s an obviously correct example, but for certain ones the other people working with their experimenter all choose the wrong one. And what they find is that the subject, even though one is clearly a better answer, a significant percentage of the time, goes along with the group because the desire to conform, or they’re doubting themselves. Now, how does that desire to conform play out in a business context and how do you fight it?

Tinna Nielsen: Well it plays out all the time. We could just ask the audience how many times they’ve been in a group of people where everybody seems to agree fast on something and you’re sitting there thinking, “Am I the only one seeing that this is absurd?” Or, “Why is nobody taking that into account? Should I say something? Should I not?” And you have that inner, like, why would you even doubt, if it’s so obvious to you. Or “Are they stupid or am I the stupid one? Nobody else is speaking up, why am I not … okay, last time I was the one speaking out, no I’m not going to do it today. I don’t want to be the weird one.”

You know, so we have all this going on all the time because we have this basic social need. And it happens in basically every meeting. So my natural instinct is to observe people’s behavior, so I immediately spot these patterns and it happens everywhere where we are together as human beings. And there are many different ways, little tangible ways people change this, really.

So back to the Asch experiment, what they also experimented with, does it make a difference if you ask people to write down their answer instead of having them say it out loud in front of everybody else? And it actually did. It actually reduced the level of conformity and the amount of people who conformed to what the others were saying, which was obviously wrong. It also makes a difference when the researchers ask one of the actors to create an alliance, like just literally look at the subject and kinda nod or wink or something. Like, you know, that’s what I see too. It also reduced the level of conformity.

And we can do this in our meetings as well. So instead of having the classical three minutes around the table where everybody’s talking or you say, “Here we have an issue we have to deal with, we have to figure out how to solve this problem.” People start talking and the first people who are talking are creating an anchor in the thought process of the other people. And then if more people chip in on that idea, then now you’re in trouble because everybody else’s mind is gonna go into this social conformity thing.

So a very easy way to change this is to present the issue for smaller groups and, you know, split the bigger group in maybe two or three groups. Present the problem in one way for one group, present it in a different way for another group, and then present it in a third way for the third group. And then have them discuss it. Before they start discussing it, have them write down on a note anonymously what they see could be my most critical inner voice right now, or an argument for or against, or, you know, you can play around with this and do it in many different ways. But the trick is to get access to people’s minds before they’ve been influenced by the other people speaking, or the strong voice.

So you know, there are many different ways you can do it, yeah. So there’s also research showing that the higher up in a hierarchy you are in an organization, the more you have a preference for a particular way of solving a problem. And the further down in the hierarchy you are, you have a different approach to solving a problem. But rarely do we get all the different kinds of problem solving approaches put into play because those who have most power kind of decide what’s the most important in terms of viewing that problem. So there are also ways that you can make sure that you actually have that diversity of problem solving approaches put into play when you’re solving a problem. So, yeah. But it’s all about trying to mitigate the group conformity, but you don’t have to talk to people about it! You can design your way around it.

Roger: Right, right. That’s some good advice for any kind of a meeting there that you have, Tinna, that instead of just saying, “Okay, what are you thinking,” and the boss speaks first and everybody else just sort of falls into line, to use some of these techniques to get people to record or share their ideas somehow first. And then go into the discussion, and you’ll end up with more diverse solutions and probably a better solution overall.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, and also little things like you can use priming, like just literally by saying “This task” or “this problem requires critical thinking.” The fact that you say critical thinking actually helps the group leverage more diversity of perspective and discuss more, have more constructive conflict. Whereas if you say, “Let’s make sure that this collaboration goes smoothly,” or, “Let’s make sure everybody feels listened to here.” Then you’ve kind of primed people’s mind to go into kind of a honeymoon kind of atmosphere where, “Let’s make sure everybody feels great.” And then we’re less inclined to have those constructive conflicts, which is very important for critical thinking. So it’s just … that’s priming, it depends on what words you use, can also have a huge impact, yeah.

Roger: Right. Well, one quick last topic I wanna talk about was another kind of nudge that you cover in the book, and that’s framing nudges. One that really surprised me was the general finding had been that female employees were less likely to say they would be interested in an international assignment than male employees, and the wording on the questionnaire that they were given, there were two original versions. “Will you take an international assignment?” Or, “Are you internationally mobile?” And those tended to produce gender skewed results, more male employees indicating they’d be willing to do it. But then there was a very minor wording change, it said, “Will you consider an international assignment at some point in the future?” And that greatly reduced the gender disparity. What was going on there? That seems like such a change that most people wouldn’t even notice but it did produce that change in responses.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah. So that’s an example that my partner in the Inclusion Nudges Initiative, Lisa Kepinski designed when she was working in a multinational organization and … so it’s actually a beautiful example. A nudge, in general, and an Inclusion Nudge are often very, very simple interventions, but they’re based on hardcore evidence. From analytical work where you really, really deep dive into what are the key issues and what is the cost of some of the problems we have or challenges we have. And also it’s based on evidence from behavioral and social science. So what Lisa was doing at the time was she was wondering, really, if it means that women … so there were a majority … many more men said “Yes” when, in the system they had to pick the box or when they were asked in appraisal interviews or development interviews, “Are you international?” Or, “Are you internationally mobile?”

And she was really wondering, is that really a picture of reality, that women don’t want to and men want to. And so she did a lot of research on this internally, and she had a lot of focus groups interviews and she was digging really deep on the data and asking questions all the time. “Why is the data not showing us?” And she realized that a lot of times, women answering the question from the present, “Are you internationally mobile?” They go, “No. My kids just started school. I have a mortgage. My mother’s sick. I have to pick up groceries on my way home.” Like, “No, I’m not internationally mobile.”

Do you have any idea if there was a follow up to see if later on women were more willing to accept the assignment, or equally willing? Because you know what it reminds me of, Tinna, is some work that was done, might’ve been by Dan Ariely or at least reported by Dan, and it’s like what people would buy at a grocery store. For consumption today, they would buy pizza. For consumption a few days later, they would buy salad and broccoli and whatnot.

Or if you were renting a video back when you rented videos as opposed to streaming them, you would bring home a documentary and an action movie and a romantic comedy or something with the intention of watching all of them, but the documentary was sort of a future thing. And it would sit on your shelf for ages, it would take much longer to watch that one, because your intentions were good it was just that at the given moment, when you were ready to watch TV, it was much more appealing to watch the action movie or romantic comedy compared to the heavy documentary.

I’m wondering if the future shifting actually changes behavior. In other words, let’s say, “Would you really like to watch this documentary in the future?” “Oh, yeah, I’d love to.” But does it change the reality when the offer is made?

Tinna Nielsen: You know, it’s actually funny that you ask. So I actually don’t know if Lisa was able to follow up, because she left the organization in 2015, I think. So I don’t know if she followed up on that. But what was interesting was that Lisa and I met when we were both working with internal head of inclusion and diversity in these two multinationals. Lisa was in France and I was in Denmark. And when we came together was a mutual acquaintance introduced us to each other, we met on Skype. And we started exchanging these very practical interventions we designed based on behavioral insights. And this was one of the first interventions Lisa shared with me.

So I brought that back to our HR executive, and we were discussing this back and forth. I was like, “Actually, we should change this as well.” And he’s like, “Yeah, but you know what the main problem is for us? It’s that the men say yes, but when it comes down to it, they say no. We have way too many men saying yes, but they turn down the offer when it comes.”

Roger: Ah, interesting.

Tinna Nielsen: So I think that for us, I think we have a different problem. They figured it out, they just say, “Yes.” But they might be saying yes because they know it’s important to say yes to have great career opportunities, “But there is something shifting,” he said. “Because it used to be that the young men, the young talent in our organization, were very keen on doing the international work, that they wanted a nice big car. They really wanted to travel, they were just like so into their career. But now,” he says, “we see a shift. Because the younger generation, they wanna spend more time with their family and their kids. They don’t care about that really nice car, they don’t wanna travel all the time. They also want time for their sports activities or playing games with their friends.” He’s like, “That’s our main problem.”

Roger: Those darn millennials.

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, but no, it’s interesting. Because that actually says a lot about these interventions. There is no one size fits all, because the culture and the context is so important. What we’re trying to do with the Inclusion Nudges Initiative, which is a purely non-profit, equal access for all, it’s not a membership thing, it’s like this, you know, go take this and go try it out in your organization.

What we do is that everything we design, we describe in a way so other practitioners or other professionals or people who … like a social entrepreneur, somebody wants to make changes. That they can read, what was the challenge, what was the intervention, how did they design it, what was the impact, what was, you know, the story behind and what are the author’s comments in terms of why does this work? What kind of behavioral drivers are we talking here?

That enables people to design it so it fits their context and their culture. So we also started collecting other people’s from our network and peers around the world. We collect their examples and help them write it up in a way so others could be inspired by it and try to make it fit some of the challenges in their organization. So that was actually the birth of the Inclusion Nudges Initiative, was to capture and collect and spread and share as many of those examples as possible so we can enable each other to make more impact faster.

Because this is not about creating a project or an initiative or a strategy or huge action plan. It’s really, and basically everything we do when we communicate, when we facilitate a meeting, when we make decisions, when we listen to an idea, what do we do with that? We have to integrate these techniques and it’s more like a basic ability. We’re trying to make it a little bit educational without people having to do a workshop or training or … that’s actually how it all started.

Roger: Right. Well, these nudges are great. I enjoyed reading. There’s a free short version of the Guidebook available online, and we’ll give everyone a link to that, where to find it.

Tinna Nielsen: And please, you know, this is an open invitation. Please join that initiative. Then you can have a weekly Inclusion Nudge and you can share with others and keep being inspired.

Roger: Well this is probably a good point to interject. Where can folks find you online and your work?

Tinna Nielsen: Yeah, so the Inclusion Nudges Initiative is called InclusionNudges.org, and when you get into that web page it’s very simple, there’s some call to action where you can sign up and join the community and you can share … you can download this free version, you can get access to the full book with the 70 examples. You can share your example, you can watch the TED Talks or read articles that other people from the community have written about this approach. Things that we’ve written ourselves.

There are different podcasts from different people like you, and thank you for the invitation to do this. It’s also there, so there’s these access to free resources. You can partner with us, you know, different ways. So yeah, it’s really about creating a global movement for how to fundamentally change how we achieve inclusiveness faster, and everybody can join for free.

Roger: Great. Well we will link there and to your TEDx video and to any other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast. And we’ll have a text version of our conversation there in handy PDF format. Tinna, thanks for being on the show!

Tinna Nielsen: Thank you so much! Really appreciate it.

Roger: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.