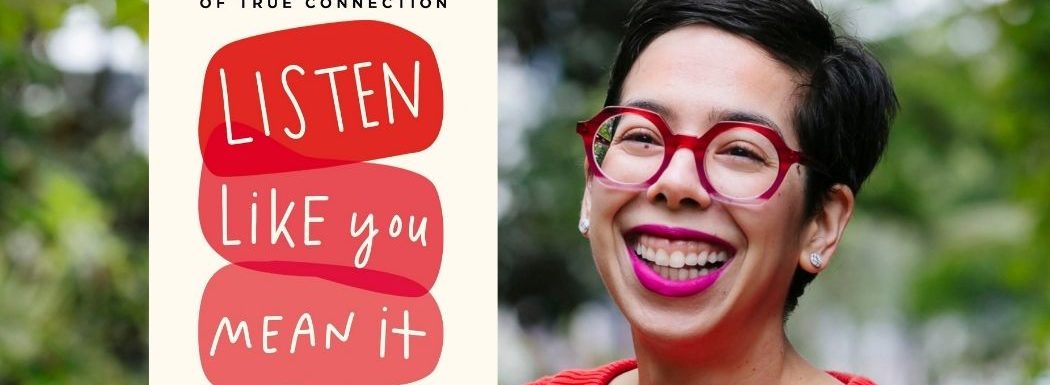

Ximena Vengoechea is a user researcher, writer, and illustrator whose work on personal and professional development has been published in Inc., The Washington Post, Newsweek, and Huffington Post. She is a contributor at Fast Company and The Muse, and is best known for her project The Life Audit. An experienced manager, mentor, and researcher in the tech industry, she previously worked at Pinterest, LinkedIn, and Twitter.

Ximena joins us today to discuss the long lost art of listening as a means of connecting with others, including how to differentiate between what people say and what they actually do, how to get away from surface listening, and how to know when to follow-up or let the conversation flow. Ximena also shares how silence is often used as a tool in user research, and how we can all use silence to our advantage when it comes to connection.

Learn how to ask the right questions to deepen customer connections with @xsvengoechea, author of LISTEN LIKE YOU MEAN IT. #listening #userexperience #UX Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How to make the distinction between what people do and what they say.

- How silence is often used in user research.

- The good and bad about user experience research that focuses on narration.

- What surface listening is and what you should be doing instead.

- The importance of watching body language in user research.

- The pros and cons of focus groups versus individual interviews.

- How going virtual has changed user research.

Key Resources for Ximena Vengoechea:

- Connect with Ximena Vengoechea: Website

- Amazon: Listen Like You Mean It

- Kindle: Listen Like You Mean It

- Audible: Listen Like You Mean It

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence I’m Roger Dooley. Today’s guest has worked in the user experience and customer experience space with some of the world’s biggest tech brands, companies like Pinterest, LinkedIn, and Twitter. She’s going to share how to better understand your customers and maybe your friends and family. Ximena Vengoechea is a user researcher, writer, and illustrator whose work has been published in Inc, The Washington Post, Newsweek, and more.

Roger Dooley: She’s a contributor at Fast Company and The Muse and is best known for her project The Life Audit. Her new book is Listen Like You Mean It: Reclaiming the Lost Art of True Connection. Welcome to the show, Ximena.

Ximena Vengoechea: Thanks so much for having me.

Roger Dooley: Ximena, many of our audience members are involved in user research, customer experience research, and they may not be doing quite the same in-depth sort of communication that you are interviewing and trying to get below that just survey type interview, where you ask somebody five questions and record their answers and really understand what they’re getting into. Explain how the work that you do fits into the bigger picture of user research, customer experience research and meshes with some of the other tools that are used in questionnaire surveys, perhaps tools of consumer neuroscience, and so on.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah, definitely. I think user research really helps us understand the why. The first thing is all of these different… You kind of mentioned survey data. Maybe it’s customer experience data. Maybe you’re looking at ticket volume complaints, that kind of thing, user research, market research, which is looking at the broader market, some of which may not actually be users, but be prospective users. There’s data science too, right? You’ve got all these different sources of information to understand your users better. The best insights are those that aren’t completely in isolation, right?

Ximena Vengoechea: That kind of come together with these other pieces of information. But where user research, and particularly qualitative research, has a core strength is the why. You can see in your behavioral data that users are dropping off on a certain page, let’s say, or not getting through a flow. But you can’t see in those graphs why. Maybe you have some theories about why they’re dropping off. The why is where you can talk to people and understand, well, what’s their experience? What kind of Headspace are they coming into when they open your app?

Ximena Vengoechea: What are some of the things that might be affecting, in this case, a drop-off or maybe signing up for your app or using it once a day instead of five times a day, which is maybe what you want? Qualitative research really tries to understand the people behind those data points. Whether that data point is self-stated through a survey where someone’s saying, “I use the product in this way,” or not self-stated, but behavioral is actually the logs of what they’re doing or how they’re using the product, but it helps you kind of dig in a little bit further and get much more nuance.

Ximena Vengoechea: Here are the contradictions that people may express or may have in how they’re using it and how they think they’re using it, all of those things, and allow you to go just that much deeper to understand that person and that set of users.

Roger Dooley: How do you know when to believe people? You make a distinction between what people do and what they say. I think that’s kind of a key element in the neuro marketing, consumer neuroscience space. That’s pretty much why that industry developed to try and get beneath what people say in surveys and questionnaires, which is often not particularly accurate, sometimes because people don’t want to say. Other times because they simply can’t say. They think they’re being truthful, but they really can’t give you those reasons. How do you know when to believe people and when to maybe not believe them?

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah, I think a lot of it… I try and think of where does the bias get baked in potentially. And that’s to me where study design matters a lot. I never want to ask a set of questions that is going to lead you to answer in a certain way. I think that’s one way of beginning to kind of strip away potential inconsistencies. There’s things like running a blind study where you don’t tell them where you’re from. You don’t say, “Hey, I’m affiliated with Pinterest or LinkedIn,” or wherever. Just say, “I’m a technology company,” or whatever it may be, or you might not tell them the topic until later.

Ximena Vengoechea: I do things in the session too to make the person feel at ease and to let them know that they don’t need to please me or my team in any way, because that’s a really common human response. You sort of want to get it “right.” You want to give the right answer. You want to look good. This is kind of an interesting opportunity. You’re talking to a tech company. I tell people I’m like neutral Switzerland. I didn’t build this product. I didn’t design this product. I’m really here to learn from you. And then I think the other thing is you are still pulling in these other pieces of information.

Ximena Vengoechea: There is what the person says, and there’s also what the person does. And you get what the person does via some of these analytics and behavioral data, but you also get it through observation. There are studies that are much more ethnographic in nature where I’m really observing. I want to see how you interact with something. And sometimes that is in a lab and I am going to prompt you to go through a flow or something like that, but sometimes it’s in the field. And it’s me going and visiting your home, right? I did, for example, a study where I really wanted to understand how people cooked.

Ximena Vengoechea: I had them keep a diary of all the times that they were meal planning, whatever that meant for them, and take photos. I got photos of the back of the pasta box and the recipes there or their cookbook or a set of recipe cards handed down from their parents. But I also went to their kitchens and I observed what was happening. And I was very careful to say, “I don’t want you to change anything for me. If your kids are normally running around the house, bring them. Don’t ask them to stay upstairs or anything like that.”

Ximena Vengoechea: There’s never 100% way of making sure that what somebody says is exactly what they mean or that you’re understanding it correctly or that gap between what they say and do. We all have our own self perception that’s always going to come into play. But through things like proper study design and not asking leading questions, and then also just bringing in observation, that helps mitigate some of those risks and helps you get a bigger picture.

Roger Dooley: I think the anonymity piece is pretty important at times because people will tend to say what they think the other person wants to hear. Before we were recording, you’re chatting about the great illustrations in your book. That is one really great aspect to it beyond the text. I think people can appreciate the audiobook because the text really has all the good information, but the illustrations that you did, Ximena, add so much to it.

Roger Dooley: But if you created some piece of art and showed it to a friend of yours and said, “What do you think,” you might get a very different response than if you said, “Hey, I bought this at a garage sale. What do you think?” People would almost certainly be much more complimentary if they knew it was yours.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah. Part of it is also in how you pose that question or even in what your follow-ups are. If I’m trying to get an honest opinion from someone and they give me what I would call like a broad statement, which is sort of like, “It’s fine, or it’s great,” something that doesn’t really… It doesn’t really give you the texture. It doesn’t really give you much nuance. That’s when I would up and ask I call them encouraging phrases. I would say, “Tell me more. Say more about that,” or one of my favorites is actually just to say because.

Ximena Vengoechea: If someone gives you a, “Yeah, I like it,” and I’d say “Because,” and you just pause and you wait for them to fill it up. “Oh, because there’s XYZ detail that’s really interesting to me, or because,” whatever it is. You give people just a little bit of encouragement to expand on their idea without having it feel like an interrogation of like, “Well, tell me what you really mean about that,” right? That would be a very different approach and probably less successful.

Roger Dooley: Well, silence is a key part of the interview process, right? Just shutting up and flighting.

Ximena Vengoechea: Exactly. I think most people are very uncomfortable with silence. It feels kind of icky to us. It feels like this conversation kind of just came to a halt, or maybe what I’m saying is not interesting and the other person isn’t responding because it’s not interesting. Most people really don’t like silence in conversation and they do everything they can to not have it be there. They’ll change the topic or, they’ll say a goodbye, say, “Okay, got to go.”

Ximena Vengoechea: But silence is really, really powerful for helping give the space for the other person to say what sometimes they maybe need to say, but haven’t been given the chance. I think sometimes silence allows us to just open up that space and get a little uncomfortable and see what comes out of it. It’s a very common tactic in user research sessions where you stay quiet and you observe. I’ll just count to 10 in my head. Most people will fill the void before you even get to 10.

Roger Dooley: What do you think about user experience research sessions that involve the person using the product and then perhaps narrating their experience as they’re going? does that give you good results, do you think, or not so good?

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah, that’s the think aloud technique where you just ask someone to do what they… “Oh, okay. Show me how you’d normally use the app and just tell me about your experience as you’re going through it, or just think aloud as you go. It’s useful. It’s useful to get a sense of how they’re experiencing the product. But of course, it can’t be the only thing for the reasons that we talked about earlier. You want to combine that with what you’re observing of how they’re using the product, maybe where they’re getting caught up on something or stuck in part of a flow.

Ximena Vengoechea: It does give you an opening to ask some of those follow-up and to say, “Oh, tell me more about that part of the page that you were talking about,” or to notice when they don’t think aloud around something. When they skip something in their think aloud process, if there’s something interesting there, I might go back and say, “Okay. There was one thing I wanted to follow up on. You mentioned this, but I also noticed this. Or did you notice this?” And so then you can kind of dig into that separately.

Roger Dooley: One term that you use that I think where probably many of us are guilty of is surface listening, which while another person is talking, we’re not entirely engaged. Explain about surface listening and also what the alternative is that’s better.

Ximena Vengoechea: Surface listening is what most of us do most of the days. It’s where most of us spend our time. That’s when we’re sort of showing up and listening without much intention. You hear enough of what the other person is saying to hold a polite conversation, to kind of nod and smile. You can often tell when someone is not fully engaged, when their mind seems to be elsewhere, or when their eyes are elsewhere. We get by with surface listening, but it’s not great because it leaves the other person feeling much less connected to you.

Ximena Vengoechea: You miss out a lot on who they are as a person and what they’re experiencing, and ultimately building a stronger relationship with them. The alternative that I talk about is empathetic listening, and that’s where you’re going beyond what’s literally being said to the emotions that that person is experiencing in a given moment. It’s not just what they’ve said or even how they’ve said it, although you’re paying attention to both of those things, but you’re making meaning kind of all the way to the core of, what is this person experiencing right now as they’re sharing this story or request for help?

Ximena Vengoechea: What might be going on here? I think that’s really important and, again, something that we don’t always make time for in conversation, because we’re busy and we have other things on our minds, but that’s where the real connection happens between human to human.

Roger Dooley: Right. Also, it lets you create a better response to whatever that person is saying. My wife and I have been married for many years, and she will describe a problem she’s having. And me being an engineer, I will immediately give her at least one solution, if not two or three solutions to that problem. And pretty soon she’s saying, “No. I know what I’m supposed to do. I know what the solutions are. I just wanted to tell you about it.” And I go, “Why are you telling me this if you didn’t want a solution?” There’s a sort of a missing communication there. Two ships passing in the opposite direction.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yes. I call that your default listening mode. So it sounds like one of your default listening modes is a problem solver. You’re listening for problems and solutions for how to solve them. And that is such a great listening mode for when there’s a problem that needs to be solved. But as you’ve learned with your wife, sometimes there’s no problem. Someone might just be venting or just wanting to think through something on their own, but they may not actually need that advice. There’s lots of different…

Roger Dooley: It’s really hard to believe, but that’s true.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yes, exactly, right? Like what? You don’t need my advice? But it is true, right? And I think there’s many listening modes. You might be more of the mediating type, someone who wants to see things from everyone’s perspective. If someone’s venting about a situation, they’ll say, “Oh well, but isn’t that person dealing with such and such, or doesn’t that have to do with this situation?” And that, again, it’s a great listening mode, except that what if somebody doesn’t want to think about things from everyone else’s point of view and they just want to hear that you understand their point of view?

Ximena Vengoechea: They just want to be validated in how they’re feeling. All of the listing modes are good, but you have to be really careful about when you bring them into conversation. Just kind of pause and think like, “Okay, my instinct is I want to give advice because this sounds like a problem to me, but is it actually?” Right? And that’s where using things like your informed intuition, like in your case, you’ve been married to your wife for some time. You’ve probably had versions of this conversation before.

Ximena Vengoechea: You maybe know a little bit more about her communication style, so you’re taking that into account, and maybe you’re also catching certain cues that she’s leaving in the conversation. You’re thinking, “Okay, she might not need my advice.” And if you’re not sure, I always suggest just asking a clarifying question. You can literally say like, “Would it be helpful to hear my advice? I have some ideas, but would that be welcome,” before you kind of launch into the list of brilliant ideas that you have, and then somebody can say, “No, no. I’m just letting you know.”

Ximena Vengoechea: I think it’s actually quite common too in direct report and managerial relationships, that specific listening filter. It’s very common.

Roger Dooley: I was about to say that, Ximena. Beyond the marriage counseling side of things, it seems like you would encounter those same situations in the office a lot, either with coworkers sometimes or with subordinate, and so on. It’s important to try and gauge what the person is really trying to tell you why they’re telling you to you before you immediately jump in with your response based on your predisposition on how to respond to anything that people say.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: Jumping back to the user experience, customer experience side of things and those types of interviews, when somebody is talking and says something interesting, how do you know when is a good time to interrupt and follow up and like digging a little bit deeper on that topic versus letting them go and maybe losing the moment that you were in there? It seems like that’s a balancing act.

Ximena Vengoechea: It definitely is, and I think there are trade-offs. Because anytime you interrupt someone, you miss out on what they were going to say. You might have an idea about what you think they’re going to say, or what you think might be more interesting, but you lose out because you’ve interrupted. And some people don’t recover well from interruptions. It’s just sort of like it’s gone. So you really have to be careful about when you interrupt.

Ximena Vengoechea: I would say what’s most common as a technique is to try not to interrupt for that reason, because you are really there for the other person to guide you in how they’re using the product, in what they’re telling you. You really try not to interrupt. However, there are some times where you might need to interrupt because you realize you’re running out of time. You haven’t gotten to the most crucial part of the study, or you have somebody who’s just rambling.

Ximena Vengoechea: And that happens, where you have someone who is repeating themselves or kind of talking in circles or going way, way off track. Your study is about LinkedIn and they’re talking about TikTok. Okay, you can interrupt there, right? But it really should be reserved for those kinds of scenarios where it’s really clear that whatever is going to be said next is just not relevant to the conversation at hand.

Roger Dooley: Ximena, talk about body language a little bit and how that adds to your understanding of what the person is saying with just their words.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah. Body language is super important and it’s one of those elements of observation that we were talking about earlier. It really helps kind of compliment what’s being said. I like to think about not just how does this person naturally show up, do they seem confident, they have kind of a large imposing posture, or maybe they’re kind of making themselves smaller and seem more insecure. It’s understanding that baseline, which you can get a pretty good read on from the minute somebody walks in.

Ximena Vengoechea: But also when does it change, if it does change, because that’s really telling of, “Ooh, we might have hit on either a sore spot.” Maybe somebody really confident suddenly starts to shrink in their seat, or maybe they stop making eye contact, or maybe their responses get softer, because I also think voice and tone is part of that observation process. When there’s a shift like that, that’s a sign to pay attention of, was it the topic? Did we start talking about something really sensitive like their personal finances and that’s uncomfortable for them?

Ximena Vengoechea: Have I done something inadvertently to make the person uncomfortable, particularly in a group setting where group dynamics start to come into play? Someone who starts out really willing to offer ideas in a group conversation suddenly stops, you want to think about why. Was it that their ideas haven’t been well received in the group? What’s the dynamic emerging?

Ximena Vengoechea: And as facilitator of that group, then that’s a cue that, “Okay, I need to help balance out this dynamic, so that person A over here who’s clearly dominating doesn’t shut person B out because they have really important things to say that I want to hear also.”

Roger Dooley: What do you think about focus groups as opposed to individual one-on-one interviews? Are there pluses and minuses?

Ximena Vengoechea: Definitely pluses and minuses. I would say one of the positives is just like in a group brainstorm, you get many more ideas generated. If you are at the beginning stages of a product say, maybe a workshop setting is great because you’re bringing lots of different voices in, or maybe you’re trying to understand a product that requires more than one person, right? That is meant for like a game, right? That has more than one player. Okay, well, that makes sense. There are certain situations where it makes a lot of sense, but there are risks.

Ximena Vengoechea: Because anytime you get a group of people together, you have things like power dynamics, which cause some people to grow quiet and some people to speak up. You have group think. You have tricky things like let’s say you have someone who would be considered to be an expert at your product in a group with someone who is considered to be a novice at your product. Well, that could be a really interesting dynamic, but it could also be super intimidating for the beginner in the group, and they might just agree with everything the expert says and pretend that they know more than they do.

Ximena Vengoechea: You don’t get a totally honest response in those scenarios. I think my general preference is for one-on-ones in part because it reduces so much of that group think. If you are going to run a focus group, think very carefully about what you’re trying to learn and whether the group dynamics will serve you or hurt your purpose.

Roger Dooley: How has going virtual change this kind of work? Hopefully pretty soon we’ll be in the same room again with total strangers, but how are you coping in the virtual world?

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah, so it’s interesting because I think in some ways, research is fairly well set up in the sense that we were already doing virtual interviews before the pandemic simply to get things like geographic diversity, right? A lot of the companies that I’ve worked at are headquartered in San Francisco. If you strictly talk to people in the Bay Area about those products, you’re going to get a very skewed, pretty techie perception. We would often fly out to different locations or conduct virtual interviews.

Ximena Vengoechea: So obviously now you don’t have the luxury of flying out to different parts of the country. Virtual is a really big and important channel for us to get those more geographically diverse participants. I think things like observation and field studies become much harder, because I can’t just be a fly on the wall in your kitchen. I have to ask you then to set up a camera in the corner kitchen or to bring me around your house and show me your closet. Let’s talk about how you shop. Bring your phone in.

Ximena Vengoechea: It’s certainly challenging, but I think so many people have adapted to this virtual first setting that they’re pretty game on the participant side. Honestly, the harder part I think is getting the message through to your teams. When you have all this virtual footage and you ask someone to sit down and watch a video or a presentation, as I’m sure you know, people are very tired of looking at a screen. So actually that piece ends up being harder than the sort of data collection piece in my opinion.

Roger Dooley: One of the interesting things early in the book, Ximena, is you talk about humility and assuming you’re in the presence of an expert. It seems like that would be very hard for many people to get their head around because almost by definition, the interviewer is the expert and the person being interviewed is the novice, the customer, or the person who may not even be familiar with the product, and so on. Explain about that a little bit more.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yeah. I share this with participants, but bringing humility into the conversation means assuming that I don’t have all the answers and assuming that what I know about the product isn’t necessarily right. You’re right in that the interviewer has a ton of information and expertise, and they know how the product is supposed to work, but the participant is really the person who’s going to use the product, or maybe not going to use the product, and so their opinion and their perspective really matters. It’s going in and it’s really removing judgment from any of the conversation.

Ximena Vengoechea: If someone can’t get through a flow, it’s not thinking, “Wow. Hmm. Well, guess they’re not going to be very good at this game,” or whatever. It’s thinking, “Oh, we thought that was a pretty easy flow. There must be something more for me to learn here.” It’s actually taking the pieces that you think that you assume to be true or right and completely putting those aside. And especially when the participant… When somebody says something in conflict with what you thought, leaning in instead of leaning back.

Ximena Vengoechea: I think the same can be said outside of the lab, in conversation with our friends or our coworkers or our spouses. If someone says something and we think, “No, no, no, that’s not right,” they share a perspective or an opinion and we have a really strong gut reaction that that’s not right, often our first response is to say some version of that’s not right, either in our head or out loud of like, “Let me tell you why that’s wrong. Let me convince you of my point of view.” But what happens then is we’ve completely altered the conversation.

Ximena Vengoechea: We no longer get a chance to learn why the person believes the things that they do, and we can shut it off right there, right? Some people are spirited debaters. Many are not and they don’t want to convince you of their point of view. By bringing that humility into those conversations, even outside of a UX lab, you give the other person a chance to share what they really mean. And when there is something that kind of goes against your beliefs, then you can lean in and try and understand why. Where did that idea come from, or how can I learn something from this moment?

Roger Dooley: Well, as a user experience researcher, you’re kind of a bridge between the customer and the people who are developing the product. What happens when you find that some group of users might, maybe not all, finds a particular feature confusing, difficult, awkward, and you go to the designers or developers and you’ll say, “Hey, they’re finding this difficult,” do you ever get that sort of push backs as well, “That’s because they’re stupid. I mean, anybody can see this is what you’re supposed to do.”

Ximena Vengoechea: Researchers have these technical skills of how to conduct a session and how to set up your study design, but there’s also a lot of soft skills. The soft skills primarily come in in situations like what you’re saying, where researchers are these neutral parties whose job is to investigate and understand users. And sometimes we’d come back with information that the team doesn’t want to hear. In that case, I think that’s where telling your story, how to understand the data, how to interpret this challenge that a user is facing becomes really important.

Ximena Vengoechea: There’s diplomacy. There’s negotiation. There’s influence, right? You don’t manage the exact products that you’re working on. You don’t manage the team that’s working on it. You are part of that team, and so you have to be able to collaborate with that team. I think actually understanding like, okay, why is this person giving me so much pushback? Why does this designer not want to make this change? Do they understand? Do they fully understand what I’m saying? Could that be part of why they’re pushing back, because they think I mean something else?

Ximena Vengoechea: Do they feel like it’s a lot of work? And if so, how can I help them understand? How can I understand their workflow? Maybe it is a lot of work and I’m treating something as a small change and it’s a huge change, right? I need to know those things too. And then also, I think when you conduct a research study and you come back with insights, you come back with recommendations for what changes should be made in the product, and it’s not… The point is not to come back with a list and say, “Here are all the things that I observed. There’s these 20 changes. Here’s the list. Goodbye.”

Ximena Vengoechea: It’s to think strategically about what do you know about the team, about the product they’re shipping, about their resources, and then to take that list and prioritize it and say, “Okay, I’m not going to give you the 20 things. I’m going to give you five things that I think are going to meaningfully change, positively impact the product. And here’s why.” And then yeah, sometimes there’s healthy debate and that’s okay. I think we talk about this idea of having enduring insights, so it’s not, “Here’s an insight and see you later. Next week, we’re onto the next insight.”

Ximena Vengoechea: It’s insights that really get taken up in the team that take time to get changed. Some things are quick and easy to change, and some things are big strategic shifts. And that’s kind of a constant, like you’re sort of the ambassador for the user along the way and doing what you can to negotiate and influence throughout the process.

Roger Dooley: Right. You need your communication skills not just with those interviewees, but also with internal team members. I think that’s probably a good place to wrap up, Ximena. How can people find you and your ideas?

Ximena Vengoechea: I’m all over the internet and have a pretty Googleable name, but my website is ximenavengoechea.com. And for the book, just add a slash listen like you mean it. I’ve also got a newsletter, which is ximena.substack.com. I’m on Twitter and LinkedIn and all that good stuff too.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to all of those places and any other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast where we’ll also have in addition to video, audio, and text versions of this conversation. Ximena, thanks so much for being on the show. Loved the book. I’ve only seen the electronic version so far. I’m really looking forward to getting the paper copy with all of those lovely illustrations.

Ximena Vengoechea: Yes, it should be coming soon. Actually I just got mine two days ago. Very exciting, but yeah, I’m sure just in a couple of weeks. Thank you so much for having me.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.