We live in an age of enlightenment. Our days are filled to the brim with apps and books and “life hacks” that will supposedly help us control our emotions and get happy. But have you ever considered that all of your emotions — not just the positive ones — could make you a smarter, happier, and more successful employee and person?

We live in an age of enlightenment. Our days are filled to the brim with apps and books and “life hacks” that will supposedly help us control our emotions and get happy. But have you ever considered that all of your emotions — not just the positive ones — could make you a smarter, happier, and more successful employee and person?

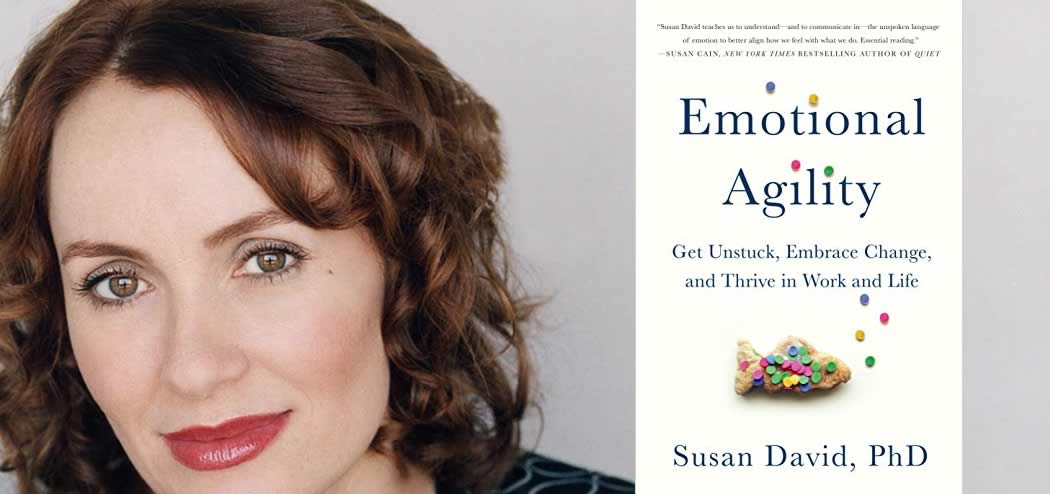

Our guest this week is Dr. Susan David, and she is an expert on this kind of thinking. Susan not only has her PhD in psychology, she is an author and the CEO of her consulting firm, Evidence-Based Psychology. Her new book, Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change, and Thrive in Work and Life, is packed with ways to make emotions into valuable workplace tools rather than distractions.

We begin by defining “emotional agility” and Susan’s primary goal: for people to bring their emotions to the workplace and become more effective, curious, and challenged employees. We talk about how organizations want to be adaptable more than ever before, which begins with adaptability on an individual level.

Susan also talks about how human beings get “hooked” on habits that don’t benefit them, and how this can impact our performance. Finally, we talk about how your emotions can benefit both you and your organization – you don’t have to check them at the office door.

Susan David, PhD, is a psychologist on the faculty of Harvard Medical School. She is also the co-founder and co-director of the Institute of Coaching at McLean Hospital, and the CEO of her consulting firm Evidence Based Psychology.

Susan has worked with senior leadership of hundreds of major organizations: the United Nations, Ernst & Young, and the World Economic Forum are just a few. Her work has been featured in many publications, including the Harvard Business Review, Time, Fast Company, and the Wall Street Journal. Originally from South Africa, she now lives outside of Boston with her family.

Susan’s insights go against what we’re often taught about the superiority of rationality over emotion. Don’t miss this chance to change your perspective on how emotions can make us better workers and people.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why simply telling your employees the company values won’t make them stick.

- How you can still make well-thought out, values-based decisions when emotional or upset.

- Why the workplace can be such a powerfully emotional environment for many people.

- How the evolution of human emotions helps us survive, and why emotion should be embraced.

- How to understand and balance the “emotional labor” that we do in the office.

Key Resources for Susan David:

- Connect with Susan: SusanDavid.com | Evidence Based Psychology | Twitter

- Amazon: Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change, and Thrive in Work and Life

- Kindle: Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change, and Thrive in Work and Life

- Audible: Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change, and Thrive in Work and Life

- Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products by Nir Eyal

- Ep #123: Be an Agile Marketer with Roland Smart on The Brainfluence Podcast

- The Tony Robbins Podcast

- “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” –Victor Frankl

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week is Susan David. Sue is a PhD psychologist on the staff at Harvard Medical School. She also has a consulting business that I know you’re going to love: Evidence Based Psychology.

Her work has been featured in the Wall Street Journal and Time magazine and the Harvard Business Review. Her new book is Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change and Thrive in Work and Life. Welcome to the show, Sue.

Susan David: Thank you for having me. It’s lovely to speak.

Roger Dooley: I singled out the name of your consultancy because most of our listeners are business people who are looking for strategies based on science or research or hard data of some kind, not the latest fad from some business guru. I suspect you’re trying to make a point with that name, Evidence Based Psychology, were you?

Susan David: I am. In all of my work with organizations what I focus on is what I call people strategy. Often when organizations think about people and employees in their organization, they wonder how the science impacts on what they do and whether the science supports what they do. So, absolutely, I’m very interested and focused on marrying robust science with practical application in organizations.

Roger Dooley: That’s great and something that I know that our listeners all appreciate. Do you think that businesses in general are getting more aware or more interested in applying research-based or evidence-based techniques as opposed to just hiring a random consultant who has some experience or expertise and so on?

Susan David: I think that there is a full range in what I’m seeing. I think that one of the aspects of organizational life that really hinders organizations is this real throwback to seeing organizations and the people within them as almost part of the industrial age.

What I mean by that is so often I come across organizations who believe that if they tell employees what their values are, of the organization, that employees will simply believe those values. Or an organization who says, “The strategy sounds logical and therefore people will elevate and work with that strategy.”

I think what organizations don’t really have a very strong handle on—and obviously it differs from organization to organization—is the people psychology of how we can help individuals to feel connected with the work that they do in a way that is actually robust and driven and spoken to by the science and research in this area.

Roger Dooley: It seems like scientific management has come full circle. Back in Taylor’s day, scientific management pretty much treated people as machines that could be optimized. Now we talk about scientific management and we’re much more into behavior science and understanding those people functioning as human beings and not necessarily automatons.

Susan David: Correct, but I do believe that there is still this idea somehow that if we discuss a strategy or discuss a sense of values within our closed door and then we send out a communication around that, that everyone is going to uptake it.

One of the things that I think is really important from an organizational perspective is people aren’t just going to believe your values because you told them that these are the values. We need to find better ways of connecting with the heart of what is going on in people within the organization and what motivates them and what connects with them.

Roger Dooley: Let’s talk about your book a little bit, Emotional Agility. Agile is a term that’s used a lot these days. Software developers use it to describe a specific approach to development projects. A couple of weeks ago, I had Roland Smart from Oracle talking about marketing agility, it’s an agile approach to marketing. Obviously, everybody wants to be agile these days but you’re coming at the term from a very different perspective. Why don’t you set the stage by explaining what you mean by emotional agility?

Susan David: Absolutely. In almost every organization there is a call for people to be agile and adaptive, and rightly so. Organizations are experiencing unprecedented technological changes, complexity, and stress. So there’s this demand almost that people within organizations be adaptable and be agile.

What I’m focusing on in Emotional Agility is the essential idea that no organization will achieve the levels of agility that it is aiming for unless the people within that organization are emotionally agile. In other words, that they have got the capacity to deal with emotions, thoughts, stories, stressors, conflict that comes at them every single day and in every single context at work.

In an organization, you might have an organization that says, “We want people to be collaborative so that we can adapt to external competitive stress. So it’s really important that our employees are adaptive and that they are collaborative and that they’re inclusive.”

I’ve never met an individual in an organization who says, “I don’t want to be inclusive and I don’t want to be collaborative.” What happens day to day is that we go into meetings where we feel stressed or undermined or “I’ve got another 300 emails to get to today.” Therefore, we put our collaboration or our inclusiveness by the way. It takes the backseat to the stresses and strains of daily life.

What is emotional agility? Emotional agility is the ability to come to your everyday thoughts, your emotions, your stories in a way that is effective, … and courageous, so that you’re able to get a real read of what the circumstances are and to make values-based, intentional decisions.

For example, if you are feeling undermined in a meeting, someone who is inagile might say to themselves, “I’m being undermined. Therefore, I’m just going to shut down.” What they’re doing is they’re conflating the situation and their response to that situation. Or, “I thought that that person didn’t think I would be effective for the project so I didn’t put my hand in for it.”

When we’re inagile, we are letting our thoughts, our emotions, our stories hold us back, drive our actions in ways that don’t serve us. When we, on the other hand, are agile, we are able to recognize that our thoughts, emotions, stories, situations, are thoughts, emotions, stories, situations. There is a person inside of that, the “us,” the heartbeat of who we are that can still make choices and can move ourselves forward in ways that are productive and effective.

Roger Dooley: One other term that you use is hooked, which also has meaning for our listeners. My friend and South by Southwest co-panelist, Nir Eyal, wrote a book called Hooked, a bestseller talking about habit-forming applications. But again, you have a very different use of the term hooked and hooks. What does that mean?

Susan David: Correct. I use the word hooked when we form habits, but habits that don’t serve us. Habits that are effectively ones where our thoughts, our emotions, our stories dominate us and where they drive us in ways that are not helpful.

Let me give you an example of one of my clients. This is an individual that I refer to in the book. This is someone who I knew through confidential information for a very, very large life changing promotion. The promotion was indirect because it was part of a larger organizational strategy. This person got wind that there was something going on. She felt that people were treating her a little bit differently. That there were conversations that were shutting down when she was coming into the room.

She got it into her head, she got hooked, on the idea that she was about to be fired. She in turn started to close down, not be transparent, be very sarcastic whenever anyone spoke about an organizational change. A couple of months later, was actually let go by the organization because they felt that her behavior was not in line with what they wanted.

What was interesting is, if you said to this individual, “What is most important to you? Who is the person you most want to be in the workplace?” Had I asked her this question, she would have said, “I want to contribute. I want to be a contributor.” What happened in this context is the difficulty that she was experiencing and the treating almost of her thoughts and emotions as fact. Therefore, letting them drive her action, led to the very opposite of who and what she wanted to be in that organizational context.

Roger Dooley: Although the behaviors you described are probably pretty much a death sentence or at least a big blocker in most organizations—although, I guess I would perhaps in the particular circumstance you described would lay a little of the blame with the management team that might have been able to communicate without obviously necessarily revealing their entire long-term strategy and the confidential information. But might have provided a little bit of encouragement to assuage her fears.

Susan David: Correct.

Roger Dooley: A good portion of the book deals with the concept of happiness. That’s something that everybody wants to be happy. The other day I was listening to a podcast and Tony Robbins, the huge motivational author or has really devoted his attention to various areas. He’s got this amazing story that involves coaching presidents and rock stars. His last big venture was teaching financial planning to people. He’s built an absolutely enormous business, like a nine figure business out of this.

One of his new concepts is what he calls the 90 second rule. In essence, that says that, yes, you’re going to have bad things come along that might depress you or make you feel sorry for yourself, but you only have 90 seconds to deal with those. Feel bad for 90 seconds, feel sorry for yourself. Then put that aside and focus on the positive. That sounds like great if you can pull it off. Do you agree with that advice?

Susan David: I admire a lot of what Tony Robbins says but I do not agree with that advice. It’s certainly not supported by the research at all. Firstly, what the research shows is that people who focus too much on the outcome of being happy, so they almost set it up as a goal for themselves. “I want to manage my day-to-day emotions because I need to be happy.” There’s a fascinating body of research that shows that those individuals over time actually end up becoming less and less happy.

There’s almost a paradox in setting up some kind of goal, orientation around happiness. That from a psychological principles approach actually serves to undermine people’s happiness.

Secondly, when you look at this idea of a 90 second rule, the research again does not support that approach at all. We live in a world where the beauty of life is inseparable from its fragilities. For example, you can be happy in a job until you are not. You can be successful at your work until you fail. So the idea that we should somehow live in a unidimensional way, being focused on only the good stuff, is really not I think a recipe for resilience and wellbeing over the longer term.

If you experience a difficulty and you start saying to yourself, “I’m only going to give myself 90 seconds to think about this difficulty,” there are two issues with that. First, we know that when people try to do what I call bottling, which is to push difficult thoughts aside, “I’m unhappy but I shouldn’t be unhappy” or “I know that the team is unhappy but I’m just not going to go there.”

We know that those kinds of bottling behaviors lead in psychology to something that we call amplification. Which is this replicable idea that when you push thoughts aside they actually come back into your mind and those very thoughts are amplified.

Anyone who’s been on a diet, tries not to think about chocolate cake, you’ll know that you start dreaming about chocolate cake. You think about chocolate cake all the time. One of the first reasons that I don’t agree with that, we know from many, many pieces of work in this area that pushing thoughts and emotions aside simply does not work.

There’s a second reason that I wouldn’t agree with that assertion around 90 seconds. That is that I believe and very much talk about in Emotional Agility the idea that thoughts and feelings are not right. They’re not fact. But they also contain very important clues to what is important to us.

For example, if someone is feeling a huge amount of frustration at work because for example they believe that their project was appropriated and they weren’t given proper credit for it. One could push that aside or one could try to understand that frustration a little bit more. What the person might discern is that the emotion is truly actually a beacon to what the person values. That the person actually values fairness. That the person values a sense of equity.

Emotions have evolved for evolutionary reasons to actually help us survive and be effective. I believe that when we push our emotions aside in the service of rationality or positivity, we actually lose very important learning information about who we are and how we want to be in the world.

Roger Dooley: I think related to that, a point you make in the book is that in an office environment, or any kind of group environment, we often mask our emotions. In other words, we may have a negative reaction to whatever the boss just proposed but we probably don’t want to always put on a really disgusted face and say something negative.

Instead, we’ll sort of smile and say, “Well that’s interesting” or “yeah, I’ll get right on that.” But you make the point that maybe that’s socially adaptive behavior but if you do that too much and too often, it can have negative consequences, right?

Susan David: Correct. I think for all us, one needs to look into inside one’s own self as a compass for how we want to be in the world. So when one is constantly reactive, as in trying to push things aside, not rock the boat, and so on, one can very often lose one’s voice and lose one’s passion and energy around a particular project or a particular situation.

Of course, you’re not going to express how you feel when you feel every single time and that’s certainly not something that I encourage in the book. What I talk about very much in the book is thinking about whether your emotions and your thoughts are in charge. Who’s in charge, the thinker or the thought? Are your emotions and thoughts in charge or is your intentionality, your values, how you want to be as a leader and how you want to be as an employee in charge in the situation?

You may, when you look inside yourself, feel that this is something that you want to talk about or have a conversation with your boss about. Not because your emotions or thoughts are driving you to but because you feel that there’s something of value that is at stake here.

Another aspect of this that’s really interesting is when you look at this kind of work that we do at work—it’s called emotional labor. The idea that every single day we go to work and we do the intellectual part of our job but we also do the emotional part of our job. We say hello nicely to everyone and we treat the customer nicely. We try to be collaborative and so on. Everyone does this kind of work. It’s emotional labor.

A large part of emotional labor is of course simply about being polite and getting by and being effective. What’s fascinating is that when we look at levels of how much people employ emotional labor, what we find is that when people are doing what we call surface acting too much, so they’re constantly putting on a show, pretending to feel other than they really do, and where they work isn’t actually connected with their values and what is important to them. Over time, those people are less likely to be effective, to be productive. It’s strongly predictive of higher levels of anxiety and burnout in the individual.

To sum, we know that emotional labor is part and parcel of work. But it’s helpful for us to think about how much emotional labor do we bring to the workplace in a way that is disconnected with what we truly value and who we are as individuals. If there’s too great a gap there to think of ways that we can try to tweak the work that we do, even within our current jobs, so that we are less employing this extreme amount of surface acting.

Roger Dooley: Right. Really what you’re trying to do is recognize the emotions that you’re experiencing for what they are, then perhaps change your behavior in some ways. I know you talk about job tweaking and job crafting to reduce the mismatch between your emotions and what you’re having to show at work.

Susan David: Correct. One of the quotes that I describe in the book is that absolutely beautiful Viktor Frankl quote. Viktor Frankl of course survived a Nazi death camp. He writes that between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space comes a choice. It is in that choice that lies our growth and freedom.

When we are being driven by our thoughts, our reactions, our interactions, our emotions, our stories, we often become very reactive to the environment and there is no space between stimulus and response. Emotional agility is effectively the practice—and it’s a learnable practice—of helping to create that space so that you can bring more of the you to the workplace in a way that is helpful and that helps to cultivate your sense of enjoyment and wellbeing at work.

While getting hooked, in the way that I described earlier, is something that we see in all parts of life, it is particularly prevalent in the workplace. The workplace evokes so much for us. Do we have high expectations or low expectations of ourselves? Do we feel good enough or not good enough? Do we feel stressed or resourced to cope with the stress?

The workplace is for many people a stage on which issues of being hooked actually play out in ways that are not so helpful to the individual.

Roger Dooley: Another sacred cow that you take issue with, a favorite of self-help gurus, is the elimination of things that trouble you. It’s the sort of thing if a friend is getting you down, then get rid of the friend. If you’re in a relationship that isn’t going all that well, get a new relationship. Sometimes I’m sure that’s good advice if a problem is simply unsolvable, but that’s not always the best advice, is it?

Susan David: Correct. I think we live in a world in which we feel that we can fix anything. We feel that we can fix and control anything and everything. There’s always an act. There’s always a technique. There’s always a something that we can be doing to fix or get rid of.

The reality I think in life is that some things can’t be fixed or controlled. Some things need to be carried. When we are able to carry a difficult experience, when we are able to carry a failure without pretending that it is other than it is, but also without letting that failure own us, then ultimately we become stronger. We become more competent and we become more effective as individuals.

Roger Dooley: I have to admit, Sue, I’ve read quite a few books involving psychology and I actually learned a few new terms in Emotional Agility. I’m just going to throw a couple of them out to you and let you explain to our listeners what they mean. I’m sure they’ll be new to them as well, or at least I expect they will be.

Susan David: Go for it.

Roger Dooley: Next week we’ll have a test and see who remembers.

Susan David: The Emotional Agility Challenge. I’m ready, tell me.

Roger Dooley: This is probably one of the best phrases in the book is technicolor thought blending.

Susan David: Love that phrase, even though I probably shouldn’t say I love a phrase that I made up. One of the things that I describe in Emotional Agility is this idea of technicolor thought blending. It is the idea that as human beings we are actually wired to get hooked.

Our brains, our psychology, the way we have evolved as a species, is to be on the alert and to process things in a very imaginative way. Technicolor thought blending is the idea that your thought doesn’t just come to you as a thought. You are not sitting in a meeting thinking, “I am being undermined and my boss has called a meeting with me tomorrow and that is just a fact.”

What we tend to do is we have this blending of thoughts and emotions where you might know that your boss has called a meeting and you experience the emotion of anxiety and fear. You might even have this image in your mind of your self being fired or your children not having enough food on the table.

The idea behind technicolor thought blending is that as human beings we are actually wired from an evolutionary perspective to get hooked. Because of course, if you are in the savanna and trying to survive, then there’s no point in saying, “I have just had the thought that I’m about to be attacked. Let me take out my iPhone and make a time for me to run away.” No, we are able to have a thought, have fear at the same time, and this image and this memory maybe of the last time we were attacked, and to run away simultaneously.

We are wired to have a thought emotion and to react to it that simultaneously. Unfortunately, that wiring doesn’t always serve us. It often takes us down a road where we act very intuitively or we are very … to something that in a way that actually doesn’t reflect who we are or what we want to be in the world.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, thinking back to the example of the woman who is perhaps due for a promotion but ended up having a vision of what was probably going to happen in the reorganization, which was incorrect. Then that guided her behavior.

Here’s number two. Premature cognitive commitment.

Susan David: I love this. I like this game. Premature cognitive commitment is really this idea that often before we’ve even thought something through, we have made a decision about how we are or aren’t going to be in a situation. For example, things like “I don’t read these kinds of books.” Or, “I am not that kind of person.” Or, “I would love to partake in this kind of career but I’m just not cut out for that.”

We all make these decisions based on who we supposedly are or aren’t as people. I’m by no means suggesting that we want to put these decisions aside because we often have learned from experience that some of those things are true or useful to us. But very often we land in situations where we then don’t put our hand up for a project, don’t put ourselves forward for a particular job, because we’ve somehow at some level decided prematurely that we are not cut out for that thing. We’ve let our story own us instead of us owning the story.

Roger Dooley: That’s great. I think we all fall into that trap of saying, “Oh, I don’t think I’d like to go to a jazz club. It’s not my favorite thing.” You have this vision without even perhaps having been in that kind of place. What it might be and saying, “I don’t like it.” Where of course I think the people that are happier are those that don’t make those kinds of assumptions about what they might or might not like. They end up going to the unusual places or volunteering for an activity that maybe is a little outside their comfort zone.

That’s probably a pretty good place to wrap up. I will remind everyone that we’re speaking with Susan David, author of the new book Emotional Agility: Get Unstuck, Embrace Change, and Thrive in Work and Life. Sue, how can our listeners find you and your content online? I know you’ve got a little special offer for our listeners.

Susan David: Absolutely, my website is susandavid.com, very easy to remember. One of the things that I have developed recently is a free online quiz. It’s lovely. It’s very short. From that, listeners actually get customized, personalized feedback, a ten-page report based on their responses around emotional agility.

If any listeners want to access that, they can go to susandavid.com/learn, S-U-S-A-N-D-A-V-I-D, L-E-A-R-N, in my wonky accent.

Roger Dooley: We will link to those places, to your book, and to any other resources we mentioned during the course of the show on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll also have a transcript of our conversation there that one can read or download as a convenient PDF for later consumption. Thanks so much for being on the show, Sue.

Susan David: Thank you for having me. That was wonderful.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.