Chris Voss Negotiation Tactics

Today’s guest is a former hostage negotiator for the FBI. Now you may be wondering what hostage negotiations have to do with you, but the answer is: a lot. Chris Voss has demonstrated that his techniques — which are rooted in brain science — crush the traditional approach to business negotiation, and we can all use his advice for negotiating within our own lives.

Get expert negotiation tips with @VossNegotiation, author of NEVER SPLIT THE DIFFERENCE. #psychology #negotiation Share on X

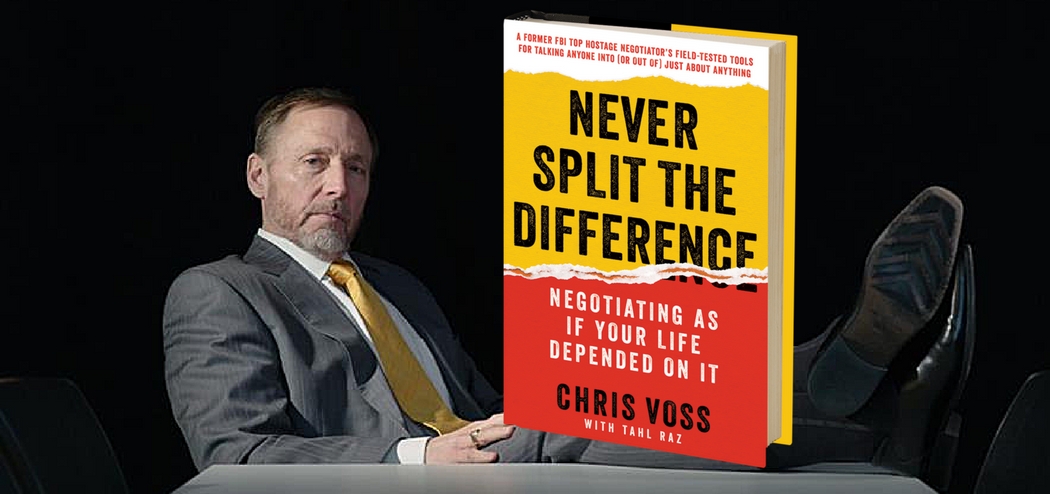

Chris’ company, The Black Swan Group, specializes in solving business communication problems using hostage negotiation solutions, and he joins the podcast today to share his expertise, as well as insights from his new book, Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It. Listen in to learn tricks for negotiating in highly emotional situations, advice for building trust, and more.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Chris Voss’s top negotiation techniques

- The similarities between hostage negotiations and business negotiations.

- Where traditional business negotiation techniques go wrong.

- How to reword open-ended questions to get unguarded responses.

- What drives 70% of purchase decisions.

- The problem with the concept of reciprocity.

- How to get people out of emotional modes of thinking into more rational modes of thinking.

- Tips for using language to diffuse emotional situations.

- How to use mirroring to create a synaptic connection in someone’s head.

- Why getting a “no” response is a good thing.

- A simple trick for getting an email response.

- Advice for negotiating a raise.

Key Resources for Chris Voss:

-

- Connect with Chris Voss: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter

- Amazon: Never Split the Difference

- Kindle: Never Split the Difference

- Audible: Never Split the Difference

- Sign up for The Black Swan Group’s Newsletter by texting FBIEmpathy to 22828

- See also Smarter Negotiation with Keld Jensen

- See also Flip the Script in Sales with Oren Klaff

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Today we have an FBI expert for our guest. This time, it’s Chris Voss, a former top hostage negotiator for the FBI. You may think that hostage negotiations don’t have much to do with you, but Chris has demonstrated that his techniques crush the traditional approach to the negotiation. And something I’m sure you’ll appreciate, his approach is rooted in brain science. When an author quotes Daniel Kahneman on system one and two, thinking in the very first chapter of the book, you know he’s on the right track.

Chris is the founder of the Black Swan group, a company that specializes in negotiation training and assistance. Chris also teaches at USC’s Marshall School of Business and Georgetown’s McDonough school. And he’s the author of the new book, Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It. Chris, welcome to the show.

Chris Voss: Roger, thank you very much for having me on. I appreciate it. It should be fun.

Roger Dooley: Well, great, Chris. I really enjoyed the book. For me, it upended a lot of things I thought I knew about negotiation.

Chris Voss: Excellent.

Roger Dooley: First, I’m curious. Over the years, there have been a number of movies and TV shows that have depicted hostage negotiations. Have you ever seen one you thought that did a reasonable job, or even a good job, of representing reality, or are they all too far fictional?

Chris Voss: No, no, no. Bits and pieces here and there. The Negotiator with Kevin Spacey and Samuel L. Jackson has got a lot of good parts in it. The biggest error there is that negotiators are never in charge. But there’s a lot of other stuff in that that’s really accurate.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, that was one of the few that I could think of that was specifically in that genre. There was another one with Russell Crowe, maybe, that-

Chris Voss: Proof of Life.

Roger Dooley: Proof of Life. Yeah, yeah. I’m curious about hostage negotiator training. Does a new negotiator sit in on real negotiations with more experienced people, or do you just get thrown into the deep end of the pool and start doing it?

Chris Voss: No, no. Well, it depends an awful lot more on what a new guy has done to prepare himself. When I was a new guy, if you will, after I got done with my training, I had actually spent a lot of time on crisis hotlines, which is pretty much exactly the same thing except we don’t got a SWAT team surrounding them. So my first major event, they put me on the phone, I was ready to rock because I’d been negotiating real life situations on a hotline for quite some time. Probably that was an unusual occurrence. Most of the time, you’re going to want somebody to warm up a little bit before you put them on the phone. But I was ready.

Roger Dooley: Chris, do you think the FBI was ahead of corporate America on adopting behavioral science? Because now we see big companies setting up behavioral science units, nudge units, and so on. But your book emphasizes dealing with cognitive biases and other strategies that are brain-based. A past guest on the show was Robin Dreeke, who was on the profiling side of things and the behavioral science side. We tend to think of government agencies as being way behind business, but is this a counter example where the FBI was actually well ahead of the curve?

Chris Voss: Yeah, I think so. The real issue is other people that are researching it and trying to invent it are also simultaneously applying it. And actually probably three things at the same time: inventing it, applying it, and teaching it. Because we were to create… it’s a virtual cycle, if you will. In many cases, in private sector like any academics who are doing a wonderful job researching and inventing, they typically don’t do much actual application in real-life scenarios because they can’t control for variables. So if you’re inventing it and applying it and teaching it all in one with the application being an important thing, which is what we did in a hostage negotiation, then yeah, I think you are ahead of the curve. You get instant feedback on what doesn’t work.

Roger Dooley: Right, and high stakes, too, of course. Before I started reading the book, Chris, I wondered really how applicable hostage negotiation strategies would be to business, because it seems just at a glance they’re quite different. There’s not really a lot of middle ground in a hostage situation. If somebody’s threatening to kill 10 hostages if they don’t get a helicopter, you can’t say, “Well, kill three and we’ll give you a van.” A typical business sort of decision, where, okay, we’ll give a little, you give a little. You can’t necessarily get to a win-win either, which is one thing that you can try and do in business. The only win for the hostage taker in most cases is walking out vertically as opposed to going out horizontally. How do you compare those two, and where do you see the similarities?

Chris Voss: You know, I initially had my doubts also, really until I went to Harvard Law School’s negotiation course. I got up there, applying my trade against the great big minds at Harvard Law, and I just did my … I thought of it at the time, my hostage negotiation stuff was kind of like street fighters’ techniques. Supposedly, there was this set of gentleman’s rules that governed business negotiations. So mine was street fighter stuff in disguise. Lots and lots of empathy, but lots of assertion disguised with the empathy.

When I just started taking them to the cleaners, I thought, “There’s got to be some overlap here.” Now, Harvard people saw it all along too. I mean, from the moment I first stepped in the door out there some really smart people, Sheila Heen, Doug Stone, Bob Mnookin, they said, “You know, you’re doing what we’re doing. We’re doing the same stuff. It’s just the stakes are different, but the principles are exactly the same.” That was really what put me on a mission to begin to apply this in the business and personal worlds.

Roger Dooley: I know that I have been schooled in the Getting to Yes philosophy and I’m sure a lot of our listeners have too in that sort of very traditional business negotiation. Where do those techniques go on, do you think?

Chris Voss: Well, Getting to Yes was originally … It’s intellectually sound. It’s just, you can’t fault it intellectually and academically. The problem is, that stuff breaks down in the real world because the real world isn’t intellectually sound. The real world is full of human beings with our biases and our desires that overwhelm rationality and very much the Daniel Kahneman stuff. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky won the Nobel Prize in behavioral economics for saying, “No, we’re not rational. We’re emotional,” and proved it. Unfortunately, that’s where getting to yes breaks down.

You can’t take an intellectual, rational approach because there’s never a moment in time where your brain’s not emotional. To pretend that you can put your emotions in neutral is exactly the same as pretending you could put your breathing in neutral. However long you can hold your breath, that’s how long you can keep your emotions in neutral. Other than that, it’s going to kick back in. That’s why, as you mentioned earlier, you said, “This is rooted in brain science.” It is.

The emotional apparatus in the brain, which is the limbic system, is never out of gear. As a matter of fact, it’s in gear when we’re asleep, which our conscious mind is not. The prefrontal cortex is not in gear. So just like our breathing, we breathe when we’re asleep, we breathe when we’re awake, our emotional architecture system, it’s in gear when we’re asleep, it’s in gear when we’re awake. And that’s where getting to yes breaks down because it assumes that you can pull that out of gear, and you can’t.

Roger Dooley: As a result, the strategies that you recommend are often kind of different than their traditional ones, which are sort of based on rational argument of, “Okay, you need X, we need Y. Maybe we can work on some other needs rather than simply butting heads on these key points.” Let’s get into a few of the specific examples or techniques. You mentioned reciprocity, which is sort of a well-established psychological principle. There, it’s pretty common, particularly in the traditional approach of trading favors, if you will, you give up something and the other person expects something in return and vice versa. But you make the point that, at least some of the time, that’s a trap, right?

Chris Voss: Well, and that’s because we’re emotional. The real key figure on this was, again, Kahneman and Tversky and Prospect Theory. They showed that a loss stings twice as much as an equivalent gain. So if I get you to give up five dollars, to me, I’m like, “All you gave me was five dollars.” But you feel like you gave up no less than 10. So consequently, there’s no fair exchange of value because neither one of us will ever valuate the same object at the same price. They’ve shown this over and over again.

I read a study recently where the issue was, or imagine your favorite bottle of wine. You love it more than anything else. If you saw it in the store and you had the money, what’s the most perfect bottle of wine worth? The answer was about $293. Okay, so now that same favorite bottle of wine, it’s in your house and one of your neighbors wants to buy it from you. What’s it worth? $1,200. These aren’t bargaining positions. This is just, what is it actually worth?

They did the same thing with tickets to your favorite concert. How much are the tickets worth to you? It’s your bucket list musician, more than anyone else. For me, I love U2 so it’s like what are tickets to U2 worth? $500. All right, so you own tickets to U2 or whatever your favorite performing musical group is, and your friend wants to buy those tickets from you. How much? $1,500. Fair price both times not screwing around, but whether we’re buying or selling, the exact same object will never come to the exact same valuation, even when we’re not bargaining or positioning. We’re just trying to be fair. So when you put that in the middle of it, then, “I’ll give you this, you give me that,” that starts to break down because none of us will ever think it’s fair.

Roger Dooley: And sometimes, simply asking an open-ended question might elicit the response you’re looking for without you having to give up anything at all.

Chris Voss: There you go. Exactly the same thing. The other crazy thing that we do as hostage negotiators, I can throw an open-ended question at you in disguise, because there are many people out there that questions of any type immediately put their guard up. I might say, “So what are you looking to get out of this?” You’ll be a little guarded. You’ll say, “Well, you know, I’m kind of thinking maybe I want this.” You’ll take your time, and you’ll even position that ask in advance because you’ll be thinking about it, your guard will be up.

The crazy nuts thing is if I say to you, “It seems like you’ve got something in mind here,” and you’ll say, “Yeah, I want this, this, this, and this,” and you’ll lay it all out. Hostage negotiators, people that we train, understand that there’s one of two ways for me to get you talking in a very unguarded way. It might be a question, and it might not. A question might be very bad, but we’re trained that we have to ask questions to gather information, and we got this stealth way of gathering information without asking questions.

Roger Dooley: Let me have an example of that, Chris.

Chris Voss: Exactly like what I said. I’ll throw it into context of a real estate example, but it’s exactly the same thing. Somebody’s walking through an open house and looking for a residential property. They walk through, they look around, and they talk to their spouse. On their way out, their realtor says, “So what did you see that you liked?” Because you obviously liked stuff, or disliked stuff.

It’s meant to be an open-ended question, which you started with the word “what”, which is one of the two key ways to start an open-ended question, is the word “what”, either “what” or “how”. Shouldn’t start with any other words. So it’s a great open-ended question. What did you see that you liked? The potential buyer might say, “Yeah, you know, we’ve got some thoughts for the future. Maybe we’re thinking about having kids, so we don’t know how this’ll fit into that.” You get an answer, but it’s going to be guarded.

Same circumstances. A husband and wife walks through, the realtor stops them, and she says, “Seems like you saw some stuff that you liked.” “Oh, yeah! You know, we’re thinking about having kids and we saw this bedroom, we saw the positioning of that bathroom, and we want to have a family room, and we want to have …” so bang, bang, bang. Usually three to four times the amount of information, so much so that one of our real estate agent trainees literally described it as “unlocking the floodgates of truth telling”.

Roger Dooley: The difference there is phrasing it in terms of a general statement as opposed to a demand for information?

Chris Voss: It’s really an observation. We refer to it as a label. The simplicity of it does not betray how complicated it really is. There’s an intentional omission of the word “I”. “It seems like you saw something you liked,” intentionally omits the word “I”. That phrase, it’s designed to actually bypass the prefrontal cortex, trigger contemplation, which then will give a more unguarded response. So it’s a very specifically designed, it’s neuroscience designed, if you will, to hit an aspect of the brain, to trigger a thought process which will come back out much more unguarded.

Roger Dooley: I really like the section on labeling. One of the techniques you talk about is labeling emotions, and that actually takes the other person sometimes out of an emotional mode of thinking into a more rational mode of thinking. Right?

Chris Voss: Right.

Roger Dooley: How would that work?

Chris Voss: Well, negative emotions bang through our brain anywhere from three to nine times at the velocity or impact or significance of positive emotions. There was a brain science experiment that was conducted where they were intentionally putting people in negative frames of mind, and they would ask them to self label. They were watching the electrical activity in their brain during this self labeling process, and they’d trigger anxiety, they’d trigger fear, they’d trigger whatever negative emotion, if you will.

Then they’d say, by showing them a photo or some other way, they’re watching the electrical activity and they’d say, “So what are you feeling right now?” And the person would think about it and then say, “Fear, but it’s going away.” The mere act of self labeling, each and every time in the experiment, dialed down, diminished, diffused, or completely defused the negative emotion.

So our label, then, is designed to trigger a self labeling process with the person and a contemplation that I talked about before. I’m going to trigger a thought process in your head, and if it’s a negative emotion, we know by and large depending upon how you measure it, negative emotions have three to nine times the impact. So I will clear your negativity to get to your positivity and it has to be sequenced like that because the negativity will otherwise overwhelm the positivity. The reasons for not doing something will overwhelm the reasons for doing something.

If I could just add one more statistic, I’ve seen some data recently said that people are 70% more likely to make a sales decision, to make a purchase to avoid loss as opposed to accomplishing gain. 70% of sales decisions are made to avoid losses. This is the negativity again. We made decisions in order to avoid loss or avoid negativity by a three to one rate of return on that.

Roger Dooley: So if you’re in a negotiation with somebody who appears to be angry about something that happened to them that you or your company or somebody might’ve caused, it might be wise to say, “You seem to be angry about the fact that your problem wasn’t handled correctly the last time,” or something like that, right, to help diffuse that?

Chris Voss: Yes, that’d be phenomenal. What you just said bordered on being a little bit long, but it identified it and it gives them the opportunity, shows respect, appreciation, fearlessness on your part, and interestingly enough, a willingness to help and it triggers all these simultaneous reactions in the person on the other side of the table, and it makes a huge difference.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, there’s one example in the book, Chris, that I think our audience can really relate to, and it was communication from the Washington Redskins, a football team, and they were trying to convert some non-paying season ticket holders. These are folks, they were season ticket holders that had not paid. It was already past time when they were supposed to have paid. The letter that was apparently going to go out or that had gone out and wasn’t working was sort of a semi-threatening, aggressive letter about the fact that they hadn’t paid yet. Then they reworded that. Why don’t you explain how they changed that and how effective it was?

Chris Voss: Yeah. One of my students, he just dropped in empathy. The thing that I always loved about that example because, yeah, people had agreed to contracts to buy season tickets and they weren’t paying. They sent out an email which they merely described as direct. In many cases, if you think you’re being direct then the other side is going to feel threatened.

Another thing I liked about this was Dan Snyder, the owner of the Redskins, gets a lot of bad press. Press loves to pick on Dan Snyder, and he got back to his season ticket people with an email saying, “Are we threatening our fans?” This is Dan Snyder showing a softer, understanding side, a more empathic side, a more astute side, which I always loved. So then they simply went back and reworded it and said, “It’s your Washington Redskins. We wouldn’t be where we are without you,” instead of, “Pay us what you owe us.” Then it said, “These times are tough for everybody, but knowing that we wouldn’t be where we are without you, how can we fix this?”

I know I’m paraphrasing this, but it was mere recognition because a lot of fans who were not paying because it was tough economic times, in their mind they’re saying like, “You know what? I’ve been supporting you for years. You wouldn’t be here without me. Now you’re giving me a hard time because I’m suddenly having trouble paying my bills when I may have paid you thousands upon thousands upon thousands of dollars over the years.” What’s the other side saying to themselves? Articulate it. They had an instant turnaround in their approach, and they pretty much worked out everything with every one of the people that were delinquent in their payments.

Roger Dooley: I think they certainly demonstrated empathy there, and they also worked the aspect of tribalism a little bit, where with the Robert Cialdini’s unity principle are basically saying that if you can show that you share an identity with somebody else, you’re more persuasive. In this case, it was sort of, “We’re all Redskins fans. We’re all part of that Redskin tribe.” Maybe I should not say it that way. They’ve got enough problems with the name “Redskins”, I guess.

Chris Voss: No, it’s all right, man. Don’t be afraid to use their title.

Roger Dooley: Anyway, I think that that really brings out another emotion, too. Probably about the only thing they missed was, it reminds me a little bit of … Cialdini had a great example of a tax letter that went out in the UK and collected a whole, like hundreds of millions of pounds of overdue taxes. There what they used was the information that most other taxpayers had already paid their taxes on time. So you had that social proof in there too, but yeah. I mean, I think it’s really …

You make a great point about how neutral direct language can really be perceived as threatening. I know, periodically in my career I’ve had to collect some overdue bills when I was working for other companies. I didn’t like to be thrust into that situation, but it always amazed me how emotional people would get when you made a simple request pointing out that, hey, this bill’s six days overdue. For them, it impugned their integrity. That’s exactly what you’re talking about, where you make a rational, logical statement and it’s taken in a much different context.

Chris Voss: It’s an attack.

Roger Dooley: Yeah.

Chris Voss: I want to go back to this tribalism thing for a second because I really want to caution people about that. Because in the moments when you hit the tribalism on the money, it can be so effective that that becomes your go-to move. Now, our negotiation approach is we’re not looking for that because what happens if you don’t have it?

Roger Dooley: Right.

Chris Voss: If that’s your move and that’s your go-to move, you’re really in trouble. That also means by definition if that’s your move, that you can’t negotiate with somebody and you can’t establish that principle, number one. I’m not interested in being restricted by that. Number two, somebody pulled that on me the other day and they got it wrong. I was offended, and I’m here to tell you I’m still offended because I gave a presentation and I said, “You know, I’m a small town boy from Iowa,” and I am. Son of Richard and Joyce Voss, Mount Pleasant, Iowa, 7,000 people in the town I grew up in.

So I get an email the following day from somebody I know right away is angling for me to do something for them for free. It starts out with him, says, “I’m a country boy like you,” and I did not say that. Now, you started off by showing me that you weren’t listening, and I’m strongly suspicious of each and every thing you say following this.

Roger Dooley: If you’re going to do it, better get it right.

Chris Voss: You better get it right. And on top of that, even if he would’ve been from Iowa, I’d have said, “All right, because so many people who are trying to hustle me, they get me to do something for nothing, that’s their opening move. So you got my guard up right off the bat. You got strike one. You got almost three strikes if you miss, and I guarantee you that so many of the hustlers out there, the used car salesmen try this, that you try this tribalism on me right off the bat, there’s a real good chance you got strike one, which means you’re already skating on thin ice. So I’m here to tell you it’s used by the manipulative types so much that the vast majority of your audience who are genuine, I’m going to tell you the well’s been poisoned in front of you a little bit.

Roger Dooley: Hmm. Interesting stuff. Chris, it seems like negotiations sometimes use techniques that are almost like psychotherapy. You have another example in the book about an executive who had to get from Austin to Baltimore and was going to lose a major contract if he didn’t get there that day. If you want to hear a really weird coincidence, I was flying from Baltimore to Austin while I was reading your book, which struck me as kind of bizarre, but it is what it is. I didn’t have any flight problems, but this guy had his original flight canceled and there was only one flight that would get him there, and it was already fully booked. I’ll let you relate the story, but I love the way he used language to, not only diffuse a potentially anxious situation, but end up getting what he wanted.

Chris Voss: Yeah. You know, the great thing about that environment, I mean, the stage was set so perfectly for him because there were so many upset people in the airport that day. The flight attendants, or the people behind the counter, just have … He followed someone who was screaming at the flight attendant. I keep saying flight attendant. The airline personnel behind the counter. I mean, this is a great setup. This is like being a comedian and having the guy that was up ahead of you get booed off the stage. Anything you say is going to be great.

He starts demonstrating understanding with her, and she just worked miracles because they can. You know, there’s an old saying, “Never be mean to someone who could hurt you by doing nothing,” which pretty much everybody, which also means that whoever you’re talking to could help you if they feel like it. The airline personnel, they got override codes, they can jump into their computer, they can waive fees right and left.

They can do so much for you if you’re just not the last jerk that was the last jerk in front of them. She even gave him a seat that wasn’t even actually yet open, but she just checked the other plane for people that were supposed to be there to make that connection that she knew were going to be late. She gave away seats that were going to be open to this guy and did it for nothing. It was crazy. All he did was he just mirrored, he labeled a little bit, he repeated the last few words. He started out by saying like, “Boy, that guy was upset.”

Roger Dooley: That’s a shrinky part I was talking about, where she would end a sentence with the weather, and then he would simply say, “The weather?” Which sounds like he ought to be laying on a couch with a psychotherapist. But what is it about that that seems to work?

Chris Voss: You know, there’s a couple things that are just darn near Jedi mind tricks. There’s something about that that causes a connection in your thought processes. Instead of, again, interrupting the person from talking, and you have to repeat the exact words that they’ve said, and it’s usually the last one to three when you get good at mirroring, which is not adopting their body language.

The hostage negotiator’s mirror is not this nonsense about walking the way they walk or stuttering the way they stutter. It’s the specific words. And there’s something that reignites the synaptic connection in someone’s head where they go on. Not only do they go on and expand, they use different words, which makes it superior to saying, “What did you mean by that?” We don’t even ask the question anymore, “What did you mean by that?” We just mirror what someone has just said, and we tend to get tons of information downloaded towards us that we could use.

Roger Dooley: I think sometimes maybe just not contradicting the person or making demands of them, but it’s probably very low-stress if somebody just repeats the last couple words that you said and lets you expand if you want to. One thing that was kind of counterintuitive, but I guess it goes with the theme, is that getting a no is important in a negotiation, which kind of flies in the face of conventional wisdom. When is the no a good thing?

Chris Voss: All the time. We don’t even bother with the word “yes”. Instead of saying to someone, “Do you agree?” I’ll say, “Do you disagree?” Instead of saying to someone, “Do you want to do this?” I’ll say, “Are you against doing this?” No creates a feeling of protection and safety in the person that utters the word. Consequently, with feelings of protection and safety, they have a tendency to begin to think more clearly and think two to three moves ahead.

We call this a calibrated no, and a calibrated no is worth at least five yeses. Because they might think as many as the answers for the next five questions that you would ask. No, as a matter of fact, it’s not a bad idea. What I need is this, this, this, and this. It moves stuff forward so quickly, even with people who are fatigued, which is another interesting issue in terms of decision fatigue as the day goes on. But people can always say no. If they can always say no, change your question so they can say no. Do you want me to fail? Are you against this? Have you given up on this? There’s any variety of changing your yes questions to no questions, and the jumpstart is enormous.

Roger Dooley: So basically what you’re saying, Chris, is that no lets people feel protected and they’re much more likely to respond, in essence, sort of agreeing with you even though they’re saying no.

Chris Voss: That’s it exactly. When you say the word “yes”, you worry about what you’ve let yourself in for. What have I missed? What’s the hook here? What’s the hidden trap? Especially if you’ve been trying to get me to say yes, I’m extra suspicious of you. So we don’t even bother with that problem. We just discard it. Yes is nothing without how anyway, so why bother with the word?

Roger Dooley: Yeah. One tip that you offer, Chris, and I’m almost afraid to share it with our audience because it seems like a really simple way to get an email response. Pretty soon, everybody’s going to be using this, but if you’re trying to get somebody to respond to your emails and you’ve done that initial contact and a couple of standard follow-ups and nothing’s happening, you suggest using a line like, “Have you given up on this project?” That’s, of course, getting that no answer, but why does that seem to work better than, “This is your last chance,” or something that might be very different than that?

Chris Voss: Well, it’s the combination of the feeling of safety and security by saying no, and then simultaneously, it puts you in the role of rescuer, and it’s very empowering to say no. It just works. We tell somebody to send an email or a text, “Have you given up on this project?” and your response will come within three minutes of the person seeing it. No joke. Across the board, our response rate on that is anywhere from 99.5% to 1,000%, and an immediate response. It’s insane.

As a matter of fact, I’ve done it to my book agent and he didn’t know it, and we’re in the meetings with the publisher because we had a round of meetings before we sold the book, and all of a sudden he went, “Holy cow! You did this to me the other day, and I remember the reaction now was I had to jump to save the issue. I felt like I was coming to the rescue.” I said, “Yeah, sorry about that.”

Roger Dooley: That’s hilarious, Chris. Let me just ask you one more question. Something that many of our listeners may have to do from time to time is ask for a raise. That can be kind of an awkward situation because there’s corporate policies and whatnot. The answer, too, that they might get is that it’s in someone else’s control. You know, corporate policy says a maximum 3%, or the big boss has to sign off on this and he said no more raises, whatever. Do you have any tips for folks in that kind of a negotiation?

Chris Voss: Well, yeah. Your salary is one term in your whole package. I actually remember sitting down and listening to the owner of the Washington Nationals baseball team about 10 years ago, and people were asking about player salaries. He was saying, “Salary’s a term.” Look at your salary as a term in a package. If you’re asking for a raise and you don’t know whether or not you’re going to get one or they’re coming back, “Well, we’re limited 3%,” here’s the bad news. I’m sorry, but I’m afraid you failed to negotiate the rest of the package. Have the package drag the salary term along with it.

You should, next time or this time, negotiate your success terms. What does it take to be successful here? How can I be involved in critical projects that are important to the strategic future of the company? You start dropping in terms that automatically increase your value. Then when you ask for salary, you’ve already demonstrated value and you’ve pulled yourself completely out of the standard conversation of, “Well, we give them 3% across the board.”

Well, if you give them 3% across the board and I’m worth so much more to you at this point in time, then the question becomes, “How am I supposed to succeed with success here based on this environment?” You make yourself more marketable, more valuable, and they’re not going to want to lose you and you actually begin to pull yourself completely out of salary conversations and into promotion conversations. With promotions come greater salaries, so it’s a sequencing issue.

Roger Dooley: Right, and you also escape those corporate rules about percentages and so on when you’re assuming a whole different position. Chris, your book is so full of great information. My copy is full of little sticky tabs, marketing stuff that I found interesting-

Chris Voss: Thank you.

Roger Dooley: … and useful. We could go on and on, but instead I will remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Chris Voss, founder of Black Swan Limited, and author of Never Split the Difference. Chris, how can our listeners connect with you?

Chris Voss: All right, so the best way is to subscribe to our newsletter. It comes out once a week and it’s the gateway to everything that we do. It’s free. It’s complementary. A former colleague of mine, still a friend, used to love to say, “If it’s free, I’ll take three.” It’s a short newsletter, anywhere from 700 to 900 words, which a couple of pages, and that’s it. You digest your article once a week.

Send a text to the number 22828. Again, the number you’re texting to is 22828. Have the message be fbiempathy, all one word. Don’t let your spell check put a space between FBI and empathy. You get a dialogue box back. It is the gateway to everything that we do, that we teach, all our training sessions, some free products on our website, which is blackswanltd.com. Help you understand where to get the best price on the book, which is Amazon, and when we’re training we have special one-day open enrollment all over the country. When one of those is coming up, you can find out about it. We will do as much for you as we possibly can to help you get better.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to those web resources to Never Split the Difference and any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. Chris, thanks for being on the show. This is going to be a book I keep on my shelf for quite a while.

Chris Voss: My pleasure, Roger. I enjoyed the conversation.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.