The spotless desk, inbox zero, the to-do-list constructed the night before: these all sound like markers of a massively productive individual. But what about those with a perpetually cluttered workspace, or those who prefer to switch between projects rather than focus on just one?

The spotless desk, inbox zero, the to-do-list constructed the night before: these all sound like markers of a massively productive individual. But what about those with a perpetually cluttered workspace, or those who prefer to switch between projects rather than focus on just one?

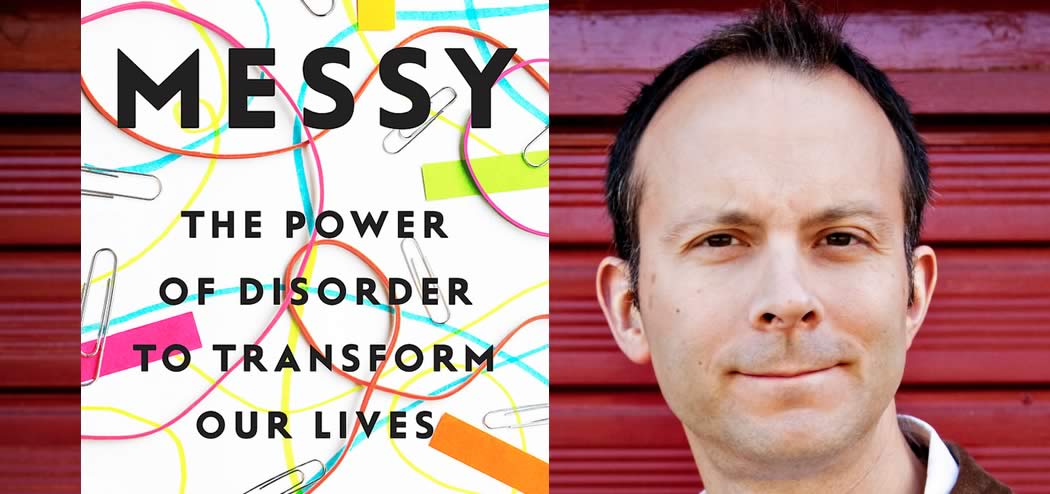

Tim Harford is an economist and writer with a knack for translating complicated ideas into compelling, digestible articles and broadcasts. His new book, Messy: The Power of Disorder to Transform Our Lives, investigates the ways in which clutter and chaos can actually breed some of the best, most groundbreaking ideas.

In this interview, Tim and I talk about why people love systems and organization, and why breaking those patterns can make ideas particularly potent. Tim also shares the messy habits of some of the world’s most creative people, and draws on research from a wide variety of fields to support the idea that working in slight disarray doesn’t mean you’re unproductive.

Tim Harford is an acclaimed economist, journalist and broadcaster. He is an author, senior columnist at the Financial Times, and the presenter of BBC Radio 4’s “More or Less.” Tim has spoken at TED and is a visiting fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford. Most recently, he was awarded the Bastiat Prize for economic journalism in 2016.

Tim’s combination of economics, sociology, and psychology is a rare and intriguing one, so be sure to catch Tim’s fascinating insights into creativity.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why people like to organize their work and space, and how this can hamper creativity.

- Whether or not it’s really advantageous to completely tune out distractions around you.

- The tension between productivity and creativity, and the role of the “flow” state.

- Tim’s tricks for staying productively distracted and switching between projects.

- Why “messy” teams tend to come up with better solutions to problems.

Key Resources for Tim Harford:

- Connect with Tim: Tim Harford | Twitter | Facebook

- Amazon: Messy: The Power of Disorder to Transform Our Lives

- Kindle: Messy: The Power of Disorder to Transform Our Lives

- Audible: Messy: The Power of Disorder to Transform Our Lives

- Kindle: The Undercover Economist: Exposing Why the Rich Are Rich, the Poor Are Poor–and Why You Can Never Buy a Decent Used Car!

- Ep #68: Disrupting Markets with Nobel Winner Al Roth on The Brainfluence Podcast

- Ep #125: The Inner Lives of Markets with Ray Fisman on The Brainfluence Podcast

- When Being Distracted Is a Good Thing from Dr. Shelley Carson of Harvard

- Uninhibited imaginations: Creativity in adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder by Holly White and Priti Shah

- Flow, the secret to happiness: TED Talk from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

- Scrivener

- Sir David Brailsford, Team Sky Cycling

- Better Decisions Through Diversity from Katherine Phillips of Northwestern

- Balasz Vedres, Network Scientist

- Steve Whittaker, UC Santa Clara

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week has a fascinating portfolio of accomplishments. He’s won too many awards for writing about economics that we can list here. He’s written for publications like Esquire, Forbes, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Wired and many more. His first book, The Undercover Economist, has been translated into 22 languages and has sold over a million copies worldwide. He has a radio show, more or less, that has won awards from such diverse groups as Health Watch and Ben-Sep.

Despite all this, he’s active on Twitter and was named one of the top 20 tweeters in the UK. Now he has a new book out that may well shake up what you think you know about organization and creativity. The book is Messy. The power of disorder to transform our lives. Welcome to the show, Tim Harford.

Tim: Thanks very much, Roger. Great to be with you.

Roger: Great. Tim, it’s really nice to have you here because you’ve got a real talent for translating scientific research into very readable prose. You make the dismal science seem a lot less dismal. Where are you speaking from today?

Tim: I am speaking from my home in Oxford in the UK.

Roger: As I suspected. I didn’t check on that before the show, but are you getting ready for Braxit there?

Tim: We are, although who knows exactly when it will happen. It sounds as though the negotiations will be triggered some time in March and then goodness only knows when it’s actually going to happen. We will see. Sometimes, even if you don’t agree with a decision, it’s good to have things shaken up and you have to learn to live under the cloud of uncertainty.

Roger: Messy, right?

Tim: Messy, indeed. Yes. This book has been good for helping me look on the bright side of certain things.

Roger: Right. Yeah, that’s the bright side of chaos. It’s got to be great fodder for a pub conversation by economists though, in the UK. Three economists walk into a bar.

Tim: Yes, of course most economists agree on what was the wise course of action and the British electorate took a different view, so plenty of fodder for conversations about why nobody listens to economists anymore. I think we’ve had a pretty good run of people listening to us so we just have to get used to people choosing to ignore us from time to time.

Roger: Right. I think the communication work that you do or you translate; some of these economic theories into something that people can understand are probably very necessary and perhaps you could clone yourself, but anyway, we’ve had some other economists on the show. I could go with that for a while. We’ve had Ray Fisman, Nobel Prize winner, Al Roth. I think we probably ought to move on to the ideas in Messy. The very concept that underlies the book, Tim, seems to be counter intuitive and contrary to just about what every business coach, productivity expert and everybody else tells us. What’s the positive side to a mess?

Tim: The basic idea of the book is that we are very fond of our systems and we like to quantify things. We like to get things down as a simple script. We like to prepare. We like to put labels on things and to organize ourselves in all kinds of different ways. Of course, that is often a very good way to proceed. A lot of civilization is built on systems. A lot of very productive people have systems to help them get things done, so I don’t want to dismiss that. What I want to say is that our love of these tidy approaches, of over-preparing, of quantifying, of systematizing, we take that and then we use it in areas where it’s not appropriate at all and it’s not helping us. It’s not helping us solve problems. It’s not helping us be better people. It’s not helping us be any smarter. It’s not helping us be any more creative.

We still desperately lean on these tidy approaches because I think they make us feel less anxious. They make us feel like we’re in control even though we’re not. I’m not saying, embrace the mess, embrace the chaos in all circumstances, but what I am saying is; if you nudge your working habits, nudge your approach, a little bit looser, a little bit more improvised, a little bit messier. You might find you get some surprising benefits from that.

Roger: You go way beyond the individual productivity aspects of mess in the book. You talk about situations where the optimal arrangement is either intentionally disrupted or where … is introduced or it may happen by accident. Do you have an all encompassing definition of mess?

Tim: It’s actually easier to define tidiness than it is to define mess. No. I think the simple answer is no, I don’t. That is somewhat in the spirit of the book. There’s no [crosstalk] theory.

Roger: It’s a messy topic.

Tim: It’s a messy topic, so, for example, I talk about musicians trying to work with instruments that aren’t properly functioning. I talk about the obvious physical mess of a messy desk or a messy office. I talk about improvisation and I also talk in quite conceptual ways about mess. For example, trusting algorithms and trusting auto-pilots versus trusting human intuition and when that works for us and what the unintended consequences will be of handing things over to the algorithm. There are lots of different topics explored in the book.

Roger: One of the topics that I found interesting were attentional filters and the different ability of people to withstand distraction and my first reaction is that having a strong ability to filter out distraction is a kind of super power. If you’re studying organic chemistry or writing computer code, random distractions are killers. You describe a study in the book that tested 25, what you term precociously creative students and these were students who had achieved really pretty phenomenal things for their age. They’d published a novel, written a play, being awarded a patent or achieved some kind of national or international honor and of those 25 students, 22 actually had a relatively weak ability to tune out distraction. That just seems to make no sense. What’s going on there?

Tim: Yeah, it’s a really striking finding, isn’t it, but conducted by Shelly Carson, who’s a psychologist at Harvard University and what they were testing was this thing called latent inhibition, which is basically a way of, can you tune out unwanted noise, unwanted conversations? You’re in a restaurant, you’re trying to focus on the conversation you’re having, can you tune out the background music, can you tune out other people’s conversations? Shelley Carson found that if you can’t, that is not a disadvantage, at least not among Harvard undergraduates. We should be clear. The population she was studying were already high achievers, like these people who are going to Harvard.

Maybe the porous attentional filters were a disadvantage, but these people had managed to overcompensate or whatever. There was a very strong correlation between having these weak filters and having these appearing to be creative in simple laboratory tests of creativity, but also having these very substantial real world creative achievements that you list. There’s not just one study. There’s another study done by Holly White and Priti Shah of people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and they find a very similar thing. More creativity in the lab and also more creativity outside the lab.

What’s going on there? It seems to me that the simple explanation is, people who can’t tune out external stimuli are; yes, they’re going to be more distracted. Yes, they may well find it more difficult to be productive, but at the same time, they are constantly being assailed with new ideas, new inputs, new grist to the creative mill. One way of thinking about it is, they think outside the box because their box is full of holes.

Roger: Is there attention between productivity and creativity? It seems that the process is that increased creativity may also tend to knock one out of a flow state that would lead to really high productivity, or is it a … You need that ability to segment creative from productive times?

Tim: I think you need to find the right balance and that’s always going to be a challenge. I think that’s a challenge we all struggle with every day, but it’s interesting that you mentioned the flow state because one of the researchers that I mention in the book, and I’m going to struggle with his name. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. You can probably do it better than me.

Roger: Yep. Csikszentmihalyi.

Tim: Csikszentmihalyi.

Roger: Yeah, I had Stephen Cutler on the show in the past and he explained that to me, so not obvious. Not a phonetic spelling.

Tim: It’s not obvious at all, but he’s very famous of course, for his work on flow, but he’s also done studies of highly creative people so he picked 100 very, very creative people. Pulitzer Price winning journalists and Nobel Prize winning scientists and people who won the Nobel Prize for literature and people who were top TV producers. Just a big variety of people. He studied their working habits and what he found. You would think, he’s into flow, right? That’s all about focus. Flow or focus are not quite the same thing and he found that all of these creative people; all of them. Not a single exception in his study had multiple projects on the go.

They’re not multi-tasking in the sense of, they’re just checking Facebook. They’re checking Twitter all the time. Not that, obviously, but they are multi-tasking in the sense that they might work on something for a few hours and then put it down and switch to something else. There were various other studies of this behavior by different psychologists, using different methods, different subject population, but you see the same thing every time. Product switching. People working on something. They stop. They work on something else and I think that’s partly because you run into diminishing returns, you get bored and if you’re bored and you need to rejuvenate yourself and find something else to do, well why not do something else that’s useful, that’s also a practical project.

It’s partly the psychological rest. If you’re feeling frustrated, you can switch to something else and make progress with that and you feel, “Oh, I’m not wasting my day”. Partly, it’s the cross-fertilization. You’re working on one thing and subconsciously, you’re also working on the thing that you were thinking about yesterday and got stuck on. You’ve stripped it of its associations. Your brain is kind of buzzing around, thinking about nothing in particular and suddenly you find a solution. Very interesting how common this behavior is. Multitasking in the usual sense, terrible news, but multiple projects and finding someway to balance them, not a bad idea at all.

Roger: You’re a really prolific writer, Tim and every writing coach that I’ve seen tells you to close everything with the software you’re writing in. Tools like Scrivener have a no distraction mode that just blacks out everything except this blank white page that you’re typing in and that sounds great, but I suspect that you might have some of the same issues that I do because often, when I’m writing, I’m researching at the same time and I have to jump on Google to track down a paper and then maybe that’s going to lead me to another research paper and so on. Sometimes you just go down a rabbit hole and you don’t accomplish anything, but other times, you make connections that you wouldn’t otherwise have made. I’ve started an article with one concept in mind and by the time I was done with it, it had gone in a rather different direction because of that process.

At the same time, when you are open to that positive distraction, you can also be distracted by the puppy video in the side bar and that sort of thing. What’s your technique?

Tim: I think you just described it. It’s difficult, because as you say, you need the internet to research in most cases. Sometimes you’ve got a good book in front of you and that’s all you need, but usually you need the internet and of course, it’s just a click away and then you disappear. That’s not, I think, terribly healthy. What I try to do and there’s no great brilliance to this, is just log out of Facebook, log out of Twitter. What happens is, you go to Wikipedia and you get some leads on some interesting research papers and you chase them up and you order the research paper or you download it and then you just, “I’ll just check Twitter”. Then, as you type in Twitter, it comes up and it says you need to log in. Then you go, “Oh yes, I remember. I’m not supposed to check Twitter”.

It’s just that, even though it would only take two seconds to log in, just that hesitation that reminds me, “Oh no, actually I’m supposed to be distracting myself, but I’m not supposed to be distracting myself with Twitter. I’m supposed to be distracting myself with the next cool research paper”. We all struggle with this and I don’t have a perfect solution. I find that helps me. The other thing that helps, actually researching all of these very successful and creative people and discovering they have multiple projects on the go helped me understand my own process a bit better. I have a weekly column for The Financial Times. I make about 20 radio programs a year. In fact, that number has just gone up because I’ve just been commissioned to do a new radio series and of course, I write my books.

There’s a shifting between working on a team at the BBC, working on the radio, working solo on a short column and then working on this big project that’s a book. I find actually, the switching between the projects is extremely helpful. I don’t find that slows me down at all. I find that grist to my creative mill. Of course, we all have to find our own way.

Roger: Changing gears. Messy teams seem to work better. That’s something that I guess is in some ways a little bit intuitive, but the teams where everyone gets along and everyone is perhaps rather similar tend not to come up with the best decisions and those teams where people are uncomfortable with other, maybe they’re fighting, things take longer and where the team may even feel the solution is worse, actually those teams perform better, right, when it comes to an objective measure of the quality of their decisions?

Tim: You’re absolutely right. Let me give you an example on two very quick studies. The example is Dave Brailsford, who is the head of the British Cycling Team and Team Sky. From British cycling being nowhere whatsoever, British cyclists now win more Olympic medals than every other country put together which is kind of impressive and they’ve also won the Tour de France several years in a row. What Brailsford says is, he is not interested in team harmony. What he wants is goal harmony. He wants everyone to be focused on the same goal. He doesn’t care if they like each other and indeed there are some pretty famous examples of people absolutely hating each other. That just doesn’t bother him. As long as everyone’s pulling in the same direction, any personal animosity is, as far as he’s concerned, not his problem. He really gets results.

That’s an anecdote, but looking at the research, there are a couple of research papers that really struck me. One was conducted by Catherine Phillips and a few colleagues at North Western University. She was studying the impact of diversity on decision making in teams. Lots and lots of research on this. Most of it finds that in most situations, if you have a diverse team, it might slow you down a bit, you might need to sort communication problems, but you’re more likely to find solutions to problems because you’ve got more different cognitive tools in the team’s toolbox. Different nationalities, different training, different perspectives. You will find it easier to find a way to crack a problem.

What Catherine Phillips did, was to ask teams of four students to solve a murder mystery problem and when she asked the teams of four friends to solve these problems, their success rate was pretty low. It was about 50/50. It’s a multiple choice; three guesses so 50/50 is not very good. When she asked three friends and one stranger to work on the problem, that’s calculated to produce maximum awkwardness. The three friends are trying to hang out and the stranger is in the room. Not very comfortable. The success rate went way up. When Catherine Phillips asked the teams how they felt, the teams of friends had a much more comfortable time, enjoyed themselves more, but also, importantly, they thought they’d done better.

This is really interesting. You’ve got a situation where a diverse team is systematically much better at solving the problem but actually doesn’t recognize that. They feel uncomfortable and they feel like they’ve failed. That explains, I think, one of the reasons why we tend to sort ourselves very tidily into teams of people who think like us, look like us, act like us and we tell ourselves it’s helping, but it’s not. That’s one study.

Another really striking study, because in this book I’ve tried to mix psychology, behavioral economics, sociology, neuroscience, just to try and get a whole bunch of different perspectives. This is a sociological study conducted by three mathematical sociologists who put together a network map of all the people who’ve ever worked in computer games. Over 100,000 people working on over 10,000 computer games since the 1970’s. It’s an amazing data set. Then they asked the question. “We can see teams forming and falling apart again. Forming, working on a couple of games and then they’d go their separate ways to work for different companies on different games”. You can see this process happening dynamically.

The question is, what kind of team makes the most successful, critically acclaimed, bestselling computer games? Think about that for a moment. You might say, “Maybe it’s a really tight knit team. People who have worked together again and again and again”. It’s not that. Then you might say, “It’s a really diverse team. Lots of different perspectives”. It’s not really that either. What it is, is networks of teams. The teams themselves are tight knit. They’ve worked together. They understand each other’s perspectives, but then they’re thrown together with other teams who have worked on very different kinds of games, very different experiences and so that’s a real recipe for tribalism.

There were three teams working on a game and team A have all worked together, team B have all worked together, team C have all worked together. They’ve all got their own perspectives and they don’t like each other. Really, really difficult situation. That’s where the best games come from. Talking to one of the researchers, Balash Vedres, he’s Hungarian; he was saying, “Yeah, this puts tremendous pressure on the managers, on the connectors who have worked with both teams in the past, who have to somehow find a way to knit the teams together”. He says these structures often don’t last. They make one or two games and then they split up, but then the Beatles split up as well. Sometimes creative genius doesn’t last.

Very interesting and challenging finding for managers who are trying to put together an effective team.

Roger: Lets move on, Tim. I think that probably just about every one of our listeners has some kind of workspace; an office, a cubicle, a desk, maybe a shared space, a shared table. Since we’re sort of teased with the ideas of focusing on personal mess, let’s talk about that a little bit. For starters, you describe an interesting experiment at University of Exeter that compared four conditions for setting up an office. A really clean office, a decorated office and then the empowered and dis-empowered variations. Explain how that worked and maybe how some of our folks can use that in their own businesses?

Tim: You know this experiment changed my life. It really did, reading about it. As you say, four conditions. In the lean condition, very minimalist. The experimenters have set up these offices and they’ve just asked people to do regular office tasks in them. In the very minimalist office, people didn’t really like it that much. They got some stuff done. In the more enriched office with posters on the walls and a pot plant, people felt a bit happier and they tended to get more done. So far, none of that’s amazingly surprising.

The really striking finding was in the empowered condition. The researchers said to people, “Here are the posters, here are the pot plants. Set it up how you want it. Put the posters where you like or we’ll take them away. Whatever you want”. Really empowering people to control their own space. Productivity soared. Now, the fourth condition. They gave people empowerment. They told them to arrange the office exactly how they wanted it and then the experimenter comes in and says, “I’m afraid we need to rearrange this”, and just altered everything. In fact, put everything back the way it had been, not had been because these are four separate arms, rather than chronological, but put everything the way it was in the enriched setting with nice posters and pot plants.

People were now being asked to work in a setting where other experimental subjects had found things perfectly fine. It was a perfectly pleasant workspace, but what’s changed is not the workspace, it’s your feeling of control. You’ve been told you can arrange it however you want and then someone has taken that control away from you and people hated it. They really hated it. They hated it in every direction. They hated the work, they hated the space, they hated the company, the really hated the experimenter. They felt physically ill and I just thought, “Think about all the times you’ve worked in an office and control over your space has been taken away. You can’t control the air conditioning. You’re not allowed to open the windows. There’s some new policy comes around. People have to clear their desks. You don’t control what posters are on the wall.

Not all offices are like this, but it’s interesting how many are given how incredibly counterproductive it seems to be and given how pointless it is. We’re not talking about a Toyota production line. We’re not talking about an operating theater. We’re just talking about a regular office where people have paperwork and email. It doesn’t really matter how it looks, but it really does matter whether people feel they have control. If you give people control, they feel happier, they’re more productive, but of course, what they do with that control is probably they make a bit of a mess, but that’s fine.

Roger: That’s a really startling finding, particularly since the second and fourth conditions ended up in the same essential condition …

Tim: Physically identical, but psychologically …

Roger: … but the control had been taken away.

Tim: Absolutely.

Roger: Fortunately I’ve been in charge of my own office for years and years as an entrepreneur, but occasionally I’ve had to deal with companies where you get the memo that, “We’ve got visitors coming in. Be sure there’s no personal photos on your desk or all papers are put away”, etc, etc. I can just see that playing out.

Tim: In the book, I spend some time just talking through the different rationales for these desk policies and there’s normally no reason at all. It’s normally completely circular and the policies are normally utterly insane. There’s one, BHP Billiton, the Australian minerals and mining company. They have this memo circulated. You’re allowed one photo or one certificate of achievement or you’ve passed a training course or whatever. You won an award, but not both. If you win an award, the penalty is you have to take the family photo down. Just doesn’t make any sense and yet somebody somewhere thought, “Well, it’ll look tidy and therefore it’s a good thing”.

Roger: It also tells you something about the individual, I guess, whether they have their engineering licence or their family photo on the wall, but these regulations get at clutter on desks and I guess I have mixed feelings about it. To use the terminology in your book, Tim, I’m more of a scruffy than neat. I’ve typically got some clutter on my desk. A stack of books to read or that I’ve partially read. File folders and a pile of business cards from the last conference I spoke at, maybe some papers that I just can’t figure out what to do with and so on. When I do make the effort to file everything away, clean it up and get to desktop zero or … There are still knickknacks and things, but at least there’s no excess work papers laying around, I feel more virtuous and I feel like I’m more productive, but then I backslide pretty quickly and in a week or two, it’s much like it was. Your book gives me some hope.

Tim: Yeah, you and Benjamin Franklin. You and Benjamin Franklin have the same approach.

Roger: Exactly. I was going to say, now I find out that I have something in common with Benjamin Franklin who, he accomplished a couple things in his life so I feel much better about myself.

Tim: You should do and lots of people have approached me since I wrote the book. Very, very successful, productive people who get loads done and said, “I feel so much better about my messy desk now”. It’s really interesting that we beat ourselves up. Nobody ever feels we have to apologize for a tidy desk, but everyone has to … They feel guilty about the messy desk. They feel they have to explain a messy desk and really, a messy desk is just a desk that’s being used. I’m a tidy person. My kitchen is tidy. My bedroom is tidy, but my desk; it varies. It’s often messy and having written the book, I feel I understand better what’s going on.

For example, a lot of people give out this piece of advice that, “You want to get organized. Everything should have a place”. Right? Everything should go in its place. When you hear that, you go, “Oh yeah, that makes sense”. Put the corkscrew in the particular place in the cutlery drawer. Here’s the place for coffee cups. It all makes perfect sense. Now, okay, what do you do with an email? Where is the place for the email? Of course, you can create a folder to put the email in, but you don’t really understand what the email is and of course, the email is attached to 100 other emails that are coming in every day so you’re having to make these decisions very, very rapidly and similarly with physical paper. That’s coming in, it’s building up on your desk.

There’s a very interesting group of people lead by Steven Whittaker, who’s a psychologist at the University of Santa Clara, who studies all the different ways, the coping strategies that we have with our digital documents and our paper documents. What Whittaker finds is that very often, tidy people try to tidy up too quickly with these documents. You’re trying to file your email by creating a folder and putting the email in a folder and then it’s not in your inbox anymore. You possibly really haven’t understood what the email is. Is it a minor thing? Is it a big project, and so because you don’t really understand what it is, you can’t file it properly and because you can’t file it properly, your filing structure doesn’t make any sense. When you come back to it, you find you can’t find the email anymore and Whittaker has this beautiful looking term for this. He calls it premature filing.

He’s not saying, don’t file, but he is saying, in many cases, leaving the paper on your desk to accumulate, leaving the email in the inbox or maybe in one bit un-categorized archive while you understand it a bit better, may be more effective. You might say, well how does this connect to productivity tips like inbox zero or de-cluttering? Actually, I find they work quite well. In my personal workflow, I find what I want to do with documents is make decisions quickly, rather than make a decision to file it quickly. If I file it, it’s gone and now I can’t figure out where it is. Often, if I can just quickly make an appropriate decision, it just disappears.

You end up, and Whittaker found this as well, that people who were filing a lot just had a lot more paperwork whereas the people who, at first glance, were messy, had lots of papers on their desk, actually the total volume of paperwork was much less because they were throwing more stuff away. They understood what they had better and what they needed to keep and what they didn’t need to keep. They had smaller archives, with more useful stuff in, but their desks were a mess. That’s the thing. We often judge on superficial metrics. You have a messy desk, you may well be a perfectly productive person and if you have a tidy desk, you may well be a very ineffective person or vice versa. It’s just appearances.

Roger: I think spacial memory, that you talk about in the book is part of that. In my very first job out of college, we had a sales manager in a large office and a large desk by comparison. Typical sort of big executive desk and what was notable about his office was on every horizontal surface, there were stacks and stacks of papers and these things might have been 12 inches deep in many cases. This was a lot of paper in this guy’s office. It was almost like a paper fortress, but what was interesting was, you could ask him about a contract from a customer from two years ago and he could retrieve it instantly because he had that spacial memory of where everything was. It may not have been the prettiest filing system and it certainly wouldn’t have met the … Wouldn’t have passed muster with the office managers that try and control those things, but in his case, it worked.

Tim: Yeah. Obviously the trouble is, if someone else either tidies it up, in which case, you’re in big trouble or someone else needs to find the paper without him.

Roger: Right, or somebody opens a window.

Tim: Yeah. I’m not saying never file. Filing is bad. Organization is always bad. I’m just saying, maybe it’s not a panacea. Don’t use it instantly and for everything because sometimes it’s okay to just let the stuff accumulate on your desk. One point that Steve Whittaker made to me; very interesting interviewing this guy. He said a lot of it depends on the nature of the information that’s coming in. If, maybe you’re an accountant listening to this podcast, you might be thinking, “Oh, this is nonsense. I can’t be piling up receipts and tax forms and so on. I need a filing system”. I would say, you’re absolutely right. You do, because the structure of the information that’s coming in, it’s actually very well organized on the way in and since it’s very well organized on the way in, you can very sensibly file it immediately and you should do that.

This is not about personality types. It’s about the nature of the work whereas, on the other hand, if you’re dealing with work that is a bit more vague, ambiguous, harder to structure, that could be for any reason. Certainly, me as a writer, a lot of the information that comes in, it’s not quite clear where it belongs, whether I need to keep it, how it relates to other things. It’s perfectly appropriate to let that sort of information sit on your desk for a bit until you understand it better. It’s not just about personality types, although it’s partly that, it’s also what kind of information you’re dealing with. As we said right at the beginning of this conversation, Roger, in some cases, an organizational system is very powerful. A structure is an incredibly good way to get things done, but sometimes it really isn’t. Sometimes you need to let go. Sometimes you need to make a mess. Sometimes you need to improvise. Sometimes that’s exactly the approach that gets things done, but we always feel just a little bit guilty when we do it that way.

Roger: Great. I could go on for hours here, I think, Tim, but let me remind our listeners. I was speaking with Tim Harford. Author of the new book, Messy. The power of disorder to transform our lives. Tim, where can our listeners find you and your content online?

Tim: My website is timharford.com. That’s Harford without a “t”. I’m also on Twitter, @timharford and on Facebook. Just search Facebook for Tim Harford. You’ll find me there, but the main source for everything, the website. Timharford.com.

Roger: Great. We’ll link to all those places, along with any other resources that we talked about during our conversation on the show notes page @rogerdooley.com/podcast and we’ll have a PDF text version of our conversation there, too, if you want to refer back to any specifics or share the podcast with a friend.

Tim, thanks so much for being on the show and good luck with the book.

Tim: It’s my pleasure. Thanks a lot, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.