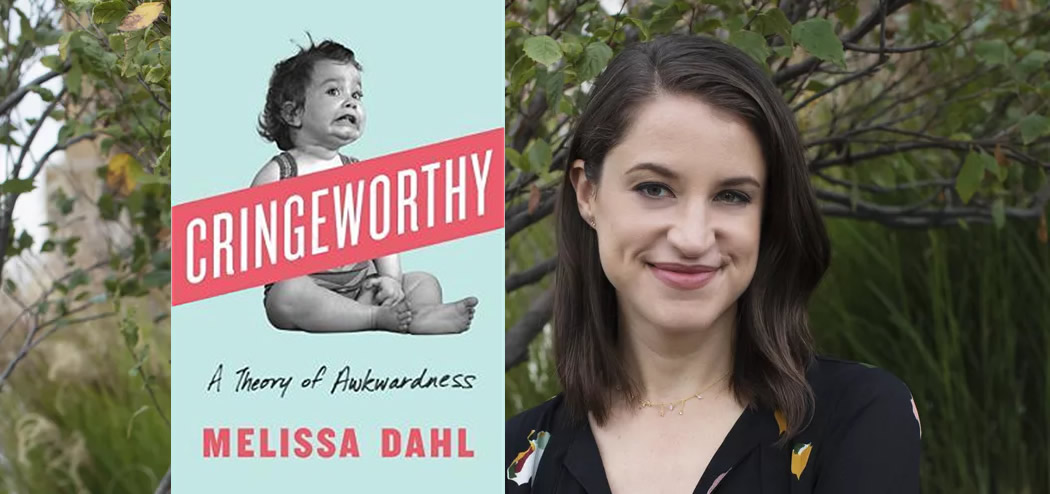

My guest this week is going to help us with a problem that makes many of us cringe—actually, she’s going to help with cringing itself. Melissa Dahl is an expert on awkwardness, and she’s here today to share advice for dealing with this uncomfortable feeling. A senior editor covering health and psychology for New York’s The Cut, Melissa cofounded New York’s popular social science site, Science of Us, in 2014. You may have also seen her work in Elle, Parents, or TODAY.com.

How you can overcome feeling awkward with @melissadahl, author of CRINGEWORTHY. #psychology #selfhelp Share on X

In this episode, you’ll hear insights from Melissa’s new book, Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness, on the science behind feeling awkward. She also gives tips for helping yourself to feel less awkward in social situations. Listen in to hear all that and more!

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Techniques for feeling less awkward.

- How to overcome the fear of uncomfortable social situations.

- Why our brains hold on to memories of feeling awkward.

- What prompted Melissa to look into the science of awkwardness.

- Why she says awkwardness is “the great equalizer.”

- The reason people dislike photos of themselves and hearing their voices on recordings.

- Why it’s a good idea to have someone else choose your profile pictures.

- What the spotlight effect is—and how it affects us.

- Tricks for changing the way you feel emotions.

Key Resources for Melissa Dahl:

-

- Connect with Melissa Dahl: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter

- Amazon: Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness

- Kindle: Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness

- Audible: Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is going to help us with a problem that makes many of us cringe. Actually she’s going to help with cringing itself. Melissa Dahl is a senior editor covering health and psychology for New York’s The Cut. In 2014 she co-founded New York’s popular social science site The Science of Us. Melissa’s new book is Cringeworthy, a Theory of Awkwardness. Welcome to the show Melissa.

Melissa Dahl: Thank you, thank you so much for having me.

Roger Dooley: Melissa for years you edited the Body Odd section at NBC News, and I just looked today and found some great headlines. One was Doctors Sew Elderly Man’s Hand Inside Stomach to Save Fingers. Another was about a patient who got a seizure from solving a sodoku puzzle. I guess they take the word odd very seriously.

Melissa Dahl: Yes.

Roger Dooley: In your tenure there did you have some favorite headlines.

Melissa Dahl: Oh my gosh, I don’t know if I remember exact headlines but I loved, I loved editing that site. It was just my favorite, favorite thing to do. I got to read … Honestly still I almost would consider it a hobby of mine reading weird medical case reports. It’s just so interesting. We wrote about alien hand syndrome, which is when sometimes after a brain injury it’s rare, but people feel like they’ve actually lost control of their hand and it’s like their own hand is moving on it’s own accord so that’s super weird.

Roger Dooley: Oh that’s creepy.

Melissa Dahl: Yes.

Roger Dooley: Although it’s a good out. I didn’t really mean to push that button, my alien hand did it.

Melissa Dahl: Exactly, or there’s Capgras delusion, which is another kind of brain disorder that happens after some kind of injury where people sincerely believe that their friends have been replaced by impostors. You look like my boyfriend but I know you are not my boyfriend. You are someone dressed up as him and I know you’re not really my boyfriend. I loved exploring the weirdness of how the mind and body work.

Roger Dooley: Right, well it’s really fascinating stuff and of course it’s actually science too, which makes it all the more fun.

Melissa Dahl: Oh yes, it felt like I was exploring the expanses of just what the brain and the body can do and what the brain and the body sometimes do of their own accord. It felt like it was exploring how wonderfully weird it is to be human, that was kind of our tagline when I was doing it, it was so fun.

Roger Dooley: Well that’s great, so your new book is maybe a little bit more serious but it’s about the science of awkwardness. That’s something that all of us feel at one time or another. What prompted you Melissa to look into this idea? Were you unusually awkward feeling much of the time or was there a trigger that sort of got you started down that path?

Melissa Dahl: There are so many things. I mean kind of my joke was, throughout writing this, well they say write what you know. I think kind of if I could briefly psychoanalyze myself, when I was a kid we moved around a lot and so I was just … Every kid, especially every teenager is hyper aware of social norms and kind of what’s cool and what isn’t and what people do and what people don’t do, what’s going to make you stand out. Every kid is aware of that, but I kind of wonder if … We moved every two years or something like that and so I had to just keep learning and relearning new social norms, new codes, these new little invisible rules that guide human behavior. I think I just became really, really atuned to the moments that are awkward that make someone kind of stand out where something kind of just goes weird, goes sideways.

I think that’s one reason, and then the other was just kind of prompted by my work here at New York Mag. In 2014 I came on to launch this site called Science of Us, which covers social science, psychology, behavior, all that kind of stuff that I love. I read about this study out of the University of Chicago, well everybody reported on it with a totally straight face but it seemed completely bonkers to me. It was this study that said psychologists asked some people on their commute into work to strike up a conversation with the person next to them on the subway, and other people just commute as you normally would. They kind of were supposed to predict how much happier, if they would be happier talking to strangers.

Everybody thought no way, that sounds awful, but then the people who did actually really enjoyed it. Like I said, everybody reported on this with such a straight face and I’m just reading this just like that sounds horrible, that sounds awful. Sort of just for fun, just because I was writing a lot back then, I was writing three to four posts a day, tried it myself for a week. I talked to strangers on the New York City subway. Kept the rules in that study, I just struck up a conversation with whoever was sitting next to me and I was surprised that it actually was kind of cool.

Roger Dooley: I’m sure you had overcome sort of a sense of fear, awkwardness to make it happen to begin with, particularly on the New York subway. I think in a lot of public situations just talking to a stranger is not a comfortable thing to do.

Melissa Dahl: It’s not a comfortable thing to do at all, but I think the cool thing about this sort of journey through this book has been I feel like awkwardness in a way is like the great equalizer, it’s something we’re all kind of afraid of, but if we can break through it and withstand it, it’s this really cool source of connection.

Roger Dooley: Something we all have in common right?

Melissa Dahl: Yes absolutely.

Roger Dooley: First I think an important distinction that you make is that, at least for the context of the book, you’re talking about awkwardness as an emotion as opposed to as a trait because I guess awkwardness can be a trait, there’s some people who are sort of inherently awkward either physically or in the way they tend to relate to all people. You focus mainly on the emotion right?

Melissa Dahl: Yes, it certainly can be a personality trait and I think that’s typically the way we think. I told people I was working on this book, they would say to me, “You don’t strike me as particularly awkward.” I would say, “Well thank you, I will take the compliment.” I feel it all the time, so it just became more interesting to me to look at it that way, particularly because I think a lot of the people who maybe are awkward as part of their personality, their maybe not bothered by it. Maybe just they say I’m not sure. Michael Scott from The Office is a good example of that. He certainly says awkward things, does awkward things, makes everyone else feel awkward but I’m not super sure he is going home kicking himself for what he said or just feeling like oh I’m so awkward I can’t do this networking thing. I can’t ask for a raise I’m too awkward. I was more interested in studying it as a feeling.

Roger Dooley: Then I think that makes sense because if we’re not inherently awkward or we don’t want to be seen as awkward that makes say an awkwardness inducing behavior all the more significant. If you walk into a room and say something unflattering about somebody and then realize that they’re sitting at the table there and you have one of these moments where, “Oh my God, did I really say that out loud?” If you’re basically an awkward person that may not bother you, but if you are sensitive enough perhaps about awkwardness to be concerned what other people think then it’s going to really greatly increase the impact on you.

Melissa Dahl: Yes, absolutely. Kind of adding to that I didn’t realize this when I kind of started thinking about it this way, but a really cool thing of understanding it as an emotion, there’s some super interesting pretty new neuroscience that says, according to these researchers, that emotions are something your brain creates essentially. The theory is the way you conceptualize an emotion kind of impacts the way you feel the emotion. If you can change the way you conceptualize an emotion, you’ll change the way you feel it. That, to me, became kind of a crucial part of this that maybe part of it is just reframing what awkwardness means and what it means to feel awkward.

Roger Dooley: I think one way that awkwardness or embarrassment is really significant is that it seems to, at least for me, to be much more memorable than other emotions. I know I can, I’m guessing you can, recall an embarrassing moment very vividly. A year later you’re still sort of kicking yourself saying, “God was I an idiot.” Where if you try and recall moments where you were happy or scared or something they just don’t seem to have the same current impact. You certainly may be able to remember the mood, but they don’t produce that sort of visceral reaction. Is that true, and if so any idea why that is?

Melissa Dahl: Yes, this was something I became kind of obsessed with finding the answer to. People who suffer a trauma or something will have flashback memories and then kind of the fear will come back just with the memory. I feel like I get that, but with my awkward or embarrassing moments, which was so weird for me to think about. I know it wasn’t traumatic when I walked out of the bathroom as an intern at MSNBC.com and had my skirt tucked into my tights. I know that wasn’t actually traumatic, so why did my brain hang onto it as if it was?

I guess the researchers I spoke to said that our brains kind of just hang on to anything, any moment that comes with a really strong emotion. They say it doesn’t matter what the emotion is, but if it’s got a really strong emotion attached to it you will hang onto it. It’s funny because I had been thinking about embarrassment as if it’s not important, but it is to us. I mean humans are one of the most social creatures on the planet. It is deeply important to us what other people think about us. I think that’s why those moments where you were afraid that you didn’t come off very well to somebody else, your brain hangs onto that and your brain is like we better remember this so we don’t do this again.

Roger Dooley: I think you may be right Melissa, and also I think that’s also what inhibits us from other interactions. You remember that time when you did something really stupid when you were talking to a stranger or some other sort of embarrassing situation happened, and that inhibits you from maybe taking advantage of opportunities that might be given to you. Not too long ago I saw a social media post from somebody who ended up sitting next to Daymond John, the entrepreneur and Shark Tank star on an airplane. I guess Daymond was reading or working and so this person didn’t interrupt him and departed the flight later and posted about it. Somehow that past got back to Daymond John himself and he posted, “Hey you should have said something. I would have enjoyed a conversation.”

I think maybe not everybody sits next to one of the sharks on an airplane, but I think that we all have those opportunities where we could say yes I could say something, maybe it’d be interesting, or maybe I can just mind my own business and it’s more comfortable to mind our own business. It could be what you were talking about Melissa, that fear of oh I remember that other embarrassing situation. I don’t want that to happen again.

Melissa Dahl: Yes, so something that was so interesting to me. First, something totally reassuring that I’ll start with is this concept of it’s called the spotlight effect. This is kind of a really great little finding in the psychology literature, and the basic idea is that people just aren’t paying as much attention to your flaws, your kind of embarrassing moments as you think. People are noticing when you do something weird or say something weird. Maybe he would have thought it was weird if you struck up a conversation with him, people do notice, but not as many people care as you think, not as many people are noticing as you think. Kind of connecting that back to that missed opportunity, I loved that study, I have written about that study many time, I have read hundreds of studies in my work as a journalist covering this stuff, and that’s one that has really stuck with me.

I got to talk to the lead author while I was writing this book and he said that idea, that initial study on the spotlight effect kind of grew out of his research on regrets. He was telling me there’s that cliché people kind of post this on Instagram and they’ve misquoted, it’s always attributed to Mark Twain, Mark Twain didn’t say this but it’s that cliché of you’ll regret the things you didn’t do more than the things you did do. According to Thomas Gilovich at Cornell, according to his research that’s really true. If it’s just the fear of looking dumb, if it’s just the fear of awkwardness that’s holding you back don’t let that hold you back.

Roger Dooley: I think that’s a good life lesson in general because I know that I certainly sometimes don’t take advantage of opportunities like that, just sort of stay in my comfort zone. My friend Noah Kagan had a suggestion for folks to get outside their comfort zone and that was to, when you’re buying coffee, ask your barista for a 10% discount, which no real reason to do or justification for, but he suggested just as a way of doing something uncomfortable so that you can then perhaps do uncomfortable things in the future that are more relevant to your life. I think it’s sort of the same thing with this. If you can sort of train yourself to talk to people on the subway, then if you end up sitting next to Mark Cuban on, well it’d probably on his private jet, but you won’t be reluctant to strike up a conversation.

Melissa Dahl: Oh yes, I mean I read specifically about this in the book about this clinical psychologist out of Boston University Affiliated Anxiety Center, but he does kind of exposure therapy where people who have social anxiety, and people have social anxiety this is fear of awkward moments to the extreme. So much that it really holds them back from doing very small things. There was a girl I heard about that used to work at a job that I had who was too afraid, she was intern, she was too afraid to even ask where the bathrooms were. Anyway, this is that kind of level of fear.

He had them kind of go through awkwardness exposure therapy essentially. He would have them dream up whatever the most embarrassing thing they could think of to do like maybe asking a clerk for a 10% discount, or there are even worse things he made them do. Then he’d be like, “Okay, go do it.” They would go out there and they would completely embarrass themselves. They would stand on a street corner and sing Mary Had a Little Lamb at the top of their lungs, or they would have to go into a bookstore and ask a book seller, “Excuse me, do you have any books about farting?” Just make themselves look completely ridiculous, and the point wasn’t to humiliate them, the point wasn’t to terrify them, the point was to, exactly like you were saying, just to prove I can do this and it’s not so bad and I survived. When I’m facing this kind of discomfort, this kind of awkwardness in my normal life I know how to handle it, I know this fear, I know how to handle it.

Roger Dooley: Does that work across domains? In other words I’ve heard of that kind of therapy for people with phobias, like if they’re afraid of snakes they’ll have them handle snakes. If you’re afraid of snakes and spiders does handling snakes also help you with spiders? In your social anxiety things do those very sort of specific experiences tend to have a benefit sort of across the board for the individuals?

Melissa Dahl: It’s exactly the same idea. Yes, I think he claims a success rate of something like 80% or something like that. I mean this is from peer reviewed research and that sort of thing. It’s the exact same idea. It’s the idea that if you kind of get used to this feeling that you’ll be better at dealing with it. Basically my whole book was a lot of just awkwardness exposure therapy for myself.

Roger Dooley: I think that even for folks that don’t have a crippling disorder really sort of practicing some of those things makes a lot of sense. Just doing things that make you a little bit uncomfortable and making a conscious effort if you’re at a business conference or something to talk to people that perhaps aren’t obviously looking for contact with you or seem to be standing alone, whatever. That you normally might just think well the guys looking at his phone, I’ll let him be, it’s probably something important, he doesn’t want to talk to me. Just go up and do that and not only because that might produce an interesting reaction but also it would accustom you to more outgoing behavior in the future.

Melissa Dahl: Absolutely and it’s not going to work every time. You might be kind of rebuffed. Maybe that guy really does just want to look at his phone, but I’ve had so much luck. I feel like I’ve just become a little bolder after doing this weird exercise in awkwardness for the last couple years. I used to completely be the person, well first of all I probably wouldn’t have gone to the networking event, but if I did I would be in the corner on my phone or I would be with the one friend I came with and not leave their side. I don’t know, I’ve gotten better at just you know … I literally just said to a girl when I went to a few months ago, I see you too are standing awkwardly alone and that probably wouldn’t work all the time but it worked and we had a great conversation.

Roger Dooley: Right, well you could also introduce yourself as the awkwardness expert.

Melissa Dahl: That’s true, that’s true. Hello, I’m queen of awkward.

Roger Dooley: Yes, you mentioned something too that talking to your friends, that’s something else that you see beyond the staring at your phone phenomenon is people who go to a networking event end up talking to only the people that they already know and not actually meeting anybody new.

Melissa Dahl: Yes or any party ends up that way. That makes sense, we like the familiar and we don’t get to see our friends that often. The point of these things is to meet somebody who might lead you to something else that’s really interesting, or maybe you’ll just have an interesting conversation. I don’t know, it’s worth taking those risks.

Roger Dooley: A few months ago Melissa, we had Daniel McGinn on the show and he wrote a book called Psyched Up and it’s a guide to being mentally prepared for a performance. One of his key strategies was to relabel anxiety as excitement so that when you’re getting ready to go on stage in front of a big crowd, your heart rate is up and maybe you’re feeling a little sweaty or something, but you can’t really control your body’s physical reaction. If you can tell yourself that it’s because you’re really excited about this and it’s going to be awesome, that relabeling actually has a very positive impact on your performance. You think that relates to awkwardness too right?

Melissa Dahl: Well absolutely, if you think about the situations we call awkward it’s often situations where we’re feeling kind of nervous or self-conscious, you’re all sweaty and you’re just like what do I say, what do I do, I’m so nervous. I love that study, again that is one of the few I’ve kind of come back to and used and remembered for years. I love that study. It’s basically the idea is, like you were saying, your body doesn’t know the difference. To your body it’s the same physiological feelings. Your body just knows something big is coming and it’s your brain that kind of is interpreting that. If you’re telling yourself it’s nerves then that means you’re ready to bolt, you’re ready to get out of there, that’s what you’re pumped up for. If you tell yourself it’s excitement then you can think of the racing heart, well sweaty armpits is not ideal, but certainly the alertness your body has it’s there on purpose, it’s there because your body knows you’re about to do something big, you need all your energy. It’s like here you go, here’s all your energy, here you go, use it.

There’s this study where this researcher Alison Wood Brooks at Harvard, she’s asked some people to try to tamp down their nervousness, like calm down, calm down, you’re not that nervous, it’ll be fine. Then they asked some people to just kind of roll with the feeling and tell themselves it was excitement. The people who did that performed a lot better at the task they had to do next, which was something awful like karaoke. I just love that. Again, this idea that you can reframe … If you reframe the way you think about a feeling it changes the way you feel it.

Roger Dooley: Yes, Melissa you have an interesting little diversion into photos and we tend to dislike photos of us. I loved your story about you having a photo that you thought was kind of particularly unattractive and then your friends reassured you that it looked just like you, which was probably not what you wanted to hear at that particular moment. I think thinking that our photos look funny or our voice sounds funny when we hear it recorded and played back to us, it’s pretty much a human characteristic. Why is that?

Melissa Dahl: Oh my gosh yes, so the photo thing, if you think about it this too deeply it gets really weird actually. You’re used to the way your face looks in a mirror. You’ve actually never seen your own face without the aid of a mirror or a photograph, which is really trippy to think about. There’s this one study where they gave people either the mirror reversed image or just the regular image of someone’s face and they had the person who was in the image rate the photos and they had a stranger rate the photos. If it’s your face you like the mirror image better because that’s the one you’re used to seeing, that’s kind of the theory that you’re just used to it. Other people tend to like the regular version of you better.

I kind of became obsessed with this idea that there’s this gap between the way you see yourself and the way that other people see you and that you can only see so much of yourself and sometimes you kind of have to depend on other people’s perception of you. There’s this psychologist at Emory University who has a name for this. He calls this the irreconcilable gap, which is this idea that sometimes the you you carry in your own mind does not exactly match up with the you other people are seeing. That kind of became the foundation for my cringe theory. When you hear your voice recorded that’s really what other people are hearing but it’s not what it sounds like in your head and that makes you cringe. I think a lot of the situations we say make us cringe are those ones where we’re sensing there’s that gap between how we’re trying to present ourselves to the world and how the world is actually perceiving us.

Roger Dooley: Melissa that kind of leads us to a takeaway I think for our listeners, and that is if you’re trying to choose a photo for your LinkedIn profile or for the cover of your book, back cover of your book, or whatever, it might be good to get the advice of other people rather than you choosing the best one because your perception of a good photo, or what that photo conveys, might not really match up with what other people are seeing.

Melissa Dahl: Oh yes, there was a study that did that. They gave people a range of photos and had strangers pick someone else’s photo for a site like LinkedIn or Facebook or something and then gave them to a different group. Oh and they had the actual person who’s face it was pick their own photo, and this third party tended to like the photo that other people picked out better than the photo that the person themselves picked out. I mean it is worth sometimes taking into consideration how other people see you and this is a very literal version of that. Maybe if you’re putting your picture on a dating profile maybe you run it by some buddies and just, “What do you think about this one? What do you think about this one?” Certainly LinkedIn, that’s one where it’s hard to get a sense of you yourself. We’re so used to ourselves. Other people sometimes can see things about us that we can’t see, so yes that’s useful.

Roger Dooley: Right, well last year we did a whole episode on choosing the best possible photo for various purposes and getting into some of the different psychology of left side is more attractive. There’s a whole series of criteria. To me one of the best thing that you could do is if you don’t have your own panel of experts then maybe use one of these apps like Photofeeler that will give you, fairly quickly, a feedback on say if it’s a business photo, the competence and trustworthiness. They have maybe three dimensions that people rate you on. I forget what they are, but you get quite a big of feedback in short order. Now I don’t think that’s a perfect process because they may use the title so that if you put CEO or intern that same photo is likely to get different ratings for competence, for example. On the other hand, it does tell the viewer what role is to be expected. If there’s a lot of dissonance between that person’s photo and the role of CEO then maybe they will get downgraded. The key message there is don’t always trust your intuition on that kind of thing.

Melissa Dahl: Yes, I mean because the funny thing is like other people can’t see what was going on in your head when you took that photo. Maybe you’re remembering that. Oh man, I was wearing that great shirt of mine, I love that shirt, it was a great day, I look great. Maybe other people think you’re projecting, your smile looks more like a smirk, that irreconcilable gap again.

Roger Dooley: Yes, it’s strange because it’s exactly as you say. There can be very subtle shades between sort of an intense gaze or a slightly crazed gaze. I’ve seem some photos like that where they’re just random borderline. Get third party input. Are there any other suggestions you can offer for either feeling less awkward or for dealing with those feelings of awkwardness Melissa?

Melissa Dahl: Yes, so one of my favorites is, so this is in the middle section of my book, a big aspect of awkwardness is feeling self-conscious. You go into a job interview and all of a sudden … I don’t think this is just me, but all of a sudden I don’t remember what to do with my hands, I don’t remember how to sit down. I was in my boss’s office for a meeting just last week and she has this nice couch with a bunch of pillows and I took one of the pillows and kind of put in on my lap and I was like, “Wait, is that a weird thing to have done? Should I put this pillow back?” It’s just those moments where you get so nervous you forget how to be a human.

There’s a reason for that. There’s all this psychology literature linking self-consciousness and nervousness. Nervousness exacerbates self-consciousness and self-consciousness exacerbates nervousness. Your nerves kind of have a way of making you narrow your focus in on yourself. When you’re nervous you kind of do that. What are my hands doing? What are my arms doing? Do I look weird? What is my face doing? What is my hair doing? I call it the awkwardness vortex. In my book it just kind of one exacerbates the other and it just gets worse and worse, you go around and around. The experts who study this say kind of the easiest way to break out of it, if it’s self-consciousness that is in part causing this then just focus on anything else. Just focus on the person in front of you, focus on the weather. One kind of tip if you are in a job interview and this kind of happens to you. Make sure you think beforehand, these are the three messages about myself and about this job that I want to get across.

This is kind of another thing that folks who study this say. If you focus on kind of the big picture, the goal it’s better than focusing in on yourself and your weird hands and what to do with your coffee cup. That should help.

Roger Dooley: Right, that is very practical I think. I guess harks back to other techniques that simply by focusing on something you can calm yourself. Obviously what you don’t want to be focused on your hands or the coffee spot on your shirt that you realized was there just as you walked into the meeting and so on. That could be a little speck but if you keep thinking about it it’s getting bigger and bigger in your mind until, from across the room, they’re joking about it.

Melissa Dahl: Yes, I started this book off, I think it was meant to cure myself of awkwardness and the first couple drafts of the first chapters I did were all about rules. Exactly how to hold your hands and exactly how to pass someone when someone is walking towards you and you do that horrible hallway dance when you can’t get by each other. You’re really like that’s not the way to think about it. I realized you just have to kind of zoom out and not focus on yourself and just focus on the bigger picture, the people in front of you, the larger goal.

Roger Dooley: Well that’s good advice and probably a good place to wrap up. Today’s guest is Melissa Dahl, Senior Editor covering health and psychology for New York Mags The Cut, and author of the new book Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness. Melissa, how can our listeners find you and your ideas?

Melissa Dahl: Yes, so you can follow me on Twitter @MelissaDahl. I’m on Twitter way too much so you can definitely find me there. Also I edit a section on The Cut called The Science of Us, which is all this kind of stuff, health and psychology if that is what you’re interested in, there’s lots of that stuff for you there. You could also buy my book.

Roger Dooley: Great, well we will link to the book and to the other places you mentioned Melissa and to any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. If you find any ideas you hear here useful, please take a moment to rate the Brainfluence podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, Player FM, or the player of your choice. Melissa, thanks for being on the show.

Melissa Dahl: Thank you so much, this was fun.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.