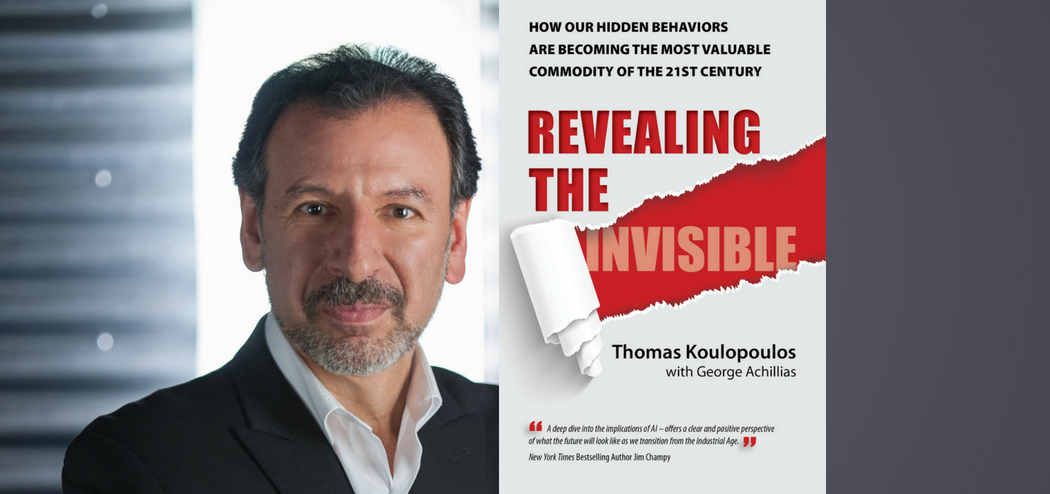

My guest today has been called “one of the truly deep thinkers in the arena of technology and culture” (Geoff James of CBS Interactive Media), and his writing has been deemed “a brilliant vision of where we must take our enterprises to survive and thrive” (Tom Peters). Thomas Koulopoulos is the chairman of the Boston-based global innovation think tank Delphi Group (which was named one of the fastest growing private companies in the US by Inc. Magazine), a columnist for Inc.com, an adjunct professor at Boston University Graduate School of Management, and an Executive in Residence at Bentley University.

Formerly the Executive Director of the Babson College Center for Business Innovation and Executive Director of the Dell Innovation Lab, Thomas has written eleven books, including Cloud Surfing: A New Way to Think About Risk, Innovation, Scale & Success and Gen Z Effect: The Six Forces Shaping the Future of Business. In this episode, he shares insights from his newest book, Revealing the Invisible: How Our Hidden Behaviors Are Becoming the Most Valuable Commodity of the 21st Century, as well as his predictions for how advancements in technology and AI will shape our future. Listen in to hear how human behavior and innovation are linked, and how the inevitable technological shifts will make our lives easier and more productive.

Learn how human behavior and innovation are linked with @TKspeaks, author of REVEALING THE INVISIBLE. #behaviorstudies #AI Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How our behavior drives innovation.

- One of the primary benefits of algorithms, intelligent machines, and AI.

- The pros and cons of our personal data in the hands of companies.

- What Thomas predicts will be the defining context of the next 100+ years.

- How AI is evolving toward knowing us better than we know ourselves.

- The difference between narrow AI and generalized AI.

- Why Thomas says businesses and institutions have evolved not to reduce friction, but to live off its heat.

- How self-operating elevators finally got popular, and how this applies to driverless cars.

- What hyper-personalization is, and how it could improve our efficiency.

- Predictions for how behavioral science will interact with all the behavioral data coming with technology.

Key Resources for Thomas Koulopoulos:

-

- Connect with Thomas Koulopoulos: Website | Twitter

- Amazon: Revealing the Invisible

- Kindle: Revealing the Invisible

- www.RevealingBook.com

- www.DelphiGroup.com

- Revealing The Invisible Trailer

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley. Author, speaker, and educator on neural marketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is Tom Koulopoulos, Chairman of the Boston based Global Innovation Think Tank Delphi Group. Tom also teaches at Boston University Graduate School of Management and Bentley University. He was previously Executive Director of the Dell Innovation Lab. Our recent guest, Tom Peters, called his writing, “A brilliant vision of where we must take our enterprises and survive and thrive.”

Tom Koulopoulos is the author of 11 books, including Cloud Surfing, and his newest title, Revealing the Invisible: How Our Hidden Behaviors Are Becoming the Most Valuable Commodity of the 21st Century. Welcome to the show, Tom.

Tom Koulopoulos: Roger, it’s a pleasure to be here. Thank you for having me.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, so Tom, Delphi Group is a think tank that’s been around for quite a few years now. What is the difference between a think tank and say, a consultancy?

Tom Koulopoulos: So we’re, yeah we’re going on 30 years now. I think we began as a consultancy and at some point, we morphed into a think tank. And I think the fundamental difference, Roger, between the two if we had to draw the line, not that we need to, is that we spend a lot more time looking at what’s coming and trying to make sense of it and rationalize it. In consulting, you’re very often in the trenches, applying well known, well worn methodologies to well known, well worn problems.

As a think tank, you’re always reaching into that area of the unknown, where it’s just not clear what the solutions are gonna be and companies struggle with this. We struggle with it as individuals. We struggle with it as a society. But I think it’s an important struggle because, hopefully we can talk about this a bit more as we get into it. We’re entering an era where so much more is unknown than is known, and we have to learn to deal with that uncertainty, to live with it. In some ways, if you will, to embrace it, and as a think tank, we have the luxury of being able to spend a lot of our time helping organizations and individuals deal with that constant din of uncertainty.

Roger Dooley: Well, that’s very interesting, although I would guess, certainly say McKinsey does some thinking as well and prognosticating but, so it’s really sort of a matter of degree and how much of your resources are located to, or allocated to dealing with, say client activities versus actually studying and thinking, and so on.

Tom Koulopoulos: Yeah, that’s a fair way to say it. You know, we love to draw lines, and draw boxes around things, and put everything into categories, and at some level whether you’re a consultancy or an adviser, a think tank isn’t necessarily all that meaningful, but I think the way you categorized it is very good. We spend a lot more of our time actually looking at what’s coming and trying to understand it, to rationalize it, and to simplify it. And that’s a very important piece of this. And on balance, I’d say probably half of our time’s spent doing that and half of it’s spent actually working in the trenches doing consulting and helping organizations actually apply these ideas.

Roger Dooley: And maybe a little bit more time to share your thinking in the form of books, too, which you’ve been quite prolific. So, yeah go ahead.

Tom Koulopoulos: I was gonna say, Roger, you know what? I think you hit something, you hit a nerve ending there, because one of my great loves is sharing knowledge, and to do that you have to keep learning. And the writing piece of it is essential to that. So one of the great luxuries of being a think tank is that you can take time to write, and to contemplate, and to try to articulate some of these issues. And that’s a huge luxury. I don’t take that for granted at all, so yes, the writing is definitely a big piece of it.

Roger Dooley: Well actually, writing’s a great way to think through problems, too. Often, people think of somebody sitting in a solitary office meditating, but that’s not really the most effective way of thinking in my experience. Sometimes, a writing and trying to explain a problem to somebody else is the best way of thinking through it yourself.

Tom Koulopoulos: No, you’re so write. I think that this is the mistaken image or the prototype we have of the author or the writer, is indeed someone who is sequestered him or herself to write. And that’s the last thing, especially in today’s world, that most writer’s do. Unless you’re writing a pure work of fiction. So, when you’re writing about these sorts of topics, artificial intelligence, autonomous cars, the future of currency, all you’re doing is talking to people. And at the end of the day, you become a filter, a sieve through which all this knowledge finds its way onto a metaphorical piece of paper. And that’s the real joy in it, is finding out from other brilliant people, where they see the trajectory of these great ideas and great technologies going. Because ultimately, it’s that wisdom of a crowd that’s most important, not the wisdom of any one person. Certainly not the author.

Roger Dooley: Yep, so in the book, Tom, you’ve got one of the better opening sentences that I’ve read. In the first sentence of chapter one, is that understanding behavior is the killer app of the 21st Century. I want you … enlarge on that a little bit.

Tom Koulopoulos: So there’s a double entendre there, and I’m so glad you picked up on that because, and a lot of people ask. It’s a joy to see a simple thought like that, a concept like that, resonate as well as it has. But here’s where it came from, here’s the Genesis of it. I’ve often said that, ultimately what causes great innovation, the kind of innovation that you hold in your hand today when you’re holding a smart phone, which has happened over the last few decades, right?

That kind of innovation is behavioral. It’s not just technological. Certainly there’s a technology behind it. There’re untold man hours of toil that go into the software and the hardware, but the technology’s meaningless, without a substantial shift in behavior. And what’s changed is our behavior. We do things with our cell phones today, we sleep we them, we have them on our nightstand, we have them on the pillow next to us. That would have been incomprehensible, I mean outright ridiculous, 10, certainly 20 years ago.

At the same time, and here’s the double entendre. At the same time, the devices themselves are beginning to exhibit behaviors. AI, autonomous vehicles. If you’ve ever driven in an autonomous car, if you haven’t, please find an opportunity to do so. What amazes you is the bond of trust that forms. It’s a behavioral bond of trust, so the idea behind that sentence was very simple. Going forward, understanding our own behaviors at a very deep level that we don’t necessarily even understand them ourselves today, our own behaviors. And also, starting to deal with, and to collaborate with machines that behave, and algorithms that behave, I think is going to be the defining context of the next hundred plus years.

And this is a very different way to think of technology, right? We’ve tried so hard not to anthropomorphize technology, to not make it human like. Well guess what, it’s becoming human like, and we better get used to it, because we will not be able to leverage it to anywhere near the big way to which I should be, if we don’t begin to look at it that way and to collaborate with it as a member of our team. Sounds so odd when you hear that, but I’m convinced in talking to so many people, that is absolutely the direction that we are taking as a society. Nothing to be afraid of. I know it’s fearful to a lot of people, but there is enormous opportunity in that, and I think it’s opportunity that will benefit all of humanity.

Roger Dooley: Tom, you mentioned that when you get a Tesla, they want you to give the car a human name, and so maybe there’s a … It sounds kind of cutesy, but you make the point that there is really something behind that.

Tom Koulopoulos: Yeah, so I don’t know if Tesla, I mean I haven’t talked to anyone at Tesla that’s confirmed this or not, so it’s partly speculation. But, confirmed whether they thought through, there was some hidden reason for having you give the car a name or not. So, but the result is, people do form a relationship with their Tesla. We write in the book about Mark Lambert, an attorney who drove coast to coast, and how he named his Tesla, Charlie, and he met a woman who named her Tesla with a male name. And it began to dawn on him that there was a relationship forming between him and the car, which is why in the book we call the chapter, A Conversation With My Car. Again, a very, it’s not the kind of thing we’re comfortable talking about, because we tried so hard to draw a line between the machine and the human. I think that line’s getting grayer and grayer by the moment.

Roger Dooley: Pretty soon, the cars will begin dating.

Tom Koulopoulos: Yeah, you know what? Here’s the thing. I’ve often said that we will know … My version of the Turing test by the way, is that we will know machines truly have intelligence when they can joke with each other and can laugh at each other’s jokes, right? So there’s a nuance to human communication and I think we’re just at the precipice of actually experiencing that kind of at least perceived intelligence in the devices.

Roger Dooley: So, how do you think, you talk a lot about collection of behavioral data, and you think that’s gonna change behavioral science itself? Because for years, we’ve had some really great insights in behavioral science, from everybody from Cialdini to Thaler and any number of other folks. Well known and lesser known. But, all to often, these studies are based on 28 MIT undergrads or small samples that are kind of specialized. And of course, that’s not totally true if some of Thaler’s data comes from large samples. Once these ideas get out in the wild and applied to total populations, then you get some bigger data, but how do you think behavioral science is going to interact with all this behavioral data that’s coming?

Tom Koulopoulos: Yeah, that’s a wonderful question. You talk about Cialdini and the whole notion of influence and the role that it plays in our decision making. I mean I think what great behavioralists have often made us aware of is that there are dynamics in how we think about the world. How we perceive events. How we make decisions that sometimes are well beyond the obvious. What drives us is not necessarily rational. What drives us is often emotional, and emotions are difficult to quantify. However, and this is a big however, what we’re realizing is that algorithms, when well trained with a large enough data set, can draw conclusions purely based on empirical data that are uncanny and in some ways frightening in their accuracy.

Now we talk about this in the book. We’ve been shown, with a very few number of likes, from 10 to 300 likes on Facebook, I can know you from as well as a colleague might with 10 likes to better than your spouse does at a few hundred likes. So, empirical data in sufficient quantity tells us a great deal through our behaviors. A great deal about who we are, about our preferences, about the way we live our lives. Now look, that is, it’s frightening to me as much as it is to anyone else, but I draw people’s attention to the fact that we’ve increasingly become a more transparent society.

So back in 1983, when Korean Airlines 007 was shot down over Russia for intruding in Russian air space, so incredible story, tragic story, right? At that time, commercial airplanes couldn’t access GPS. I mean, today I can’t leave my house without a GPS. We’ve become that attached to the technology. We need it that much and-

Roger Dooley: And dependent on it too, I think our brains have evolved to forget how to navigate by any other means than a telephone.

Tom Koulopoulos: Well, so let’s come back to that in a minute, because I think you’re spot on. So GPS was a wane wish, our behaviors were exposed in dramatic ways. We’re tracked like wildlife today. On the other hand, I can’t imagine being a parent and not knowing where my children are. Not that my parents obviously didn’t know where I was during the day. But I can’t live without that. So, our behaviors change, our expectation changes, but guess what? Our level of safety and security also changes. I mean, we become a much safer society. We become a society that, because of our transparency, has the opportunity to influence in ways that we never had before.

We understand the workings of government in ways that we never had before. So this general increase in transparency is helping every aspect of us socially, economically. It’s creating interreliance that I think is essential in this global economy that we inhabit. So, look there’s a lot of good stuff coming out of this. The problem is that we don’t see the good stuff until we’re 10 to 20 years after the moment of crisis, which is kind of where we are right now. So the exposure of behavioral data is at the very least annoying, and at the very best terrifying. But we have to work through this, negotiate who’s gonna own our digital identities. We talk about it’s so great in the book, today I don’t own my digital self. Facebook, and Apple, and Microsoft own it.

So we have to get beyond some short term issues that are gonna be quite trying for us as a society. But on the other side of that, I believe there’s enormous indications on the positive side for us as individuals, for our businesses, for our economies. And frankly, for 10 billion people of which today it’s seven and a half billion. I think a good three billion are totally disenfranchised. They have no identity, they have no bank accounts. They don’t have the opportunities that the rest of the world has. So that I think will change in large part, because of the things that we’re talking about today, and in the book, and that’s what excites me about this topic.

Roger Dooley: For people to own their data, is that a technical evolution or a legal evolution, or both?

Tom Koulopoulos: Yeah, it’s both. It has to be both, and I think I’m not, you know I tend to fall on the side of, keep government out of it whenever possible. But I do think this is one area where was do have to get government involved. I think having a legal identity, a digital self from the moment of birth is an essential asset for every human being. And maybe the most valuable asset that most human beings have, as we move forward and begin to establish that. Part of it is technical, clearly, but part of it has to be legislated. It is legal as you say, and that takes time. We know from experience, we saw this with Zuckerberg’s testimony on the Hill. Our legislators are not necessarily the most technically adept people in the world either.

So, there’s a lot of education that has to happen here, but hey look, you know what? In 20-30 years, all the kids we call millennials today or GenZers, they’ll be making the laws. so, I have no doubt that we will get to a level of competency and understanding technically to be able to take on the challenge. It’s just that right now, things have moved so fast that, that’s not where most legislators are.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So are there companies that already have more data about us than Facebook out there, or Google say?

Tom Koulopoulos: In the book we actually talk about, there are myriad companies that have been doing this for quite some time. Longer than Facebook has. I think it could be argued, I teach a course on cybersecurity. It could be argued that the NSA probably has more data on us than all of the above combined, however when we look at this from a commercial standpoint, it is-

Roger Dooley: Maybe they should do an IPO.

Tom Koulopoulos: It would be a helluva IPO, you know I would-

Roger Dooley: Big day to play.

Tom Koulopoulos: … I would agree with you, that would be a helluva IPO. We have to look at this from the standpoint of, how is the data being used, and where’s the value to me as an individual? And set the NSA aside for a second, because we can argue if there are national security implications there, but we take those on in the book and I think there’s certainly some headway to be made in how our data is mined by governments or by nation states, but let’s look at the easier problem. The commercial entities like the Facebooks, the Microsofts, the Apples, the Googles. What bothers me today is not how much they know about me, but how little I know about how much they know about me.

So you can go to Facebook, you can go to Google, you can download your history. It’s enlightening and eye opening to see how much they know about you, but, and this is a big but, today that digital identity is still very fragmented and segmented. Facebook owns a piece of it, Google owns a piece of it, Apple owns a piece of it, but no one entity owns all of it. And I think over the next 10 years, what we’ll see is consolidation of these small pools of knowledge about me, about my digital self, into aggregated versions of my digital self that are amazingly prescient and can predict my behaviors and my actions before I can. Amazon, Netflix are players in this as well, right?

So very fragmented today, and I think what we need to do is make sure that from a legislative standpoint, we keep pace with this issue of ownership. How my data can be used, under what terms it’s used, at least as fast as that consolidation is going to occur. Because within 10 years time, there will be an owner of a significant piece of my digital self. Significant enough, so that it should at that point, frighten me if I don’t have legal recourse by which to manage and to exert ownership and control over that.

Roger Dooley: And right now, under their terms of service, these entities can typically transfer this data to other parties, right?

Tom Koulopoulos: Well that’s the big issue see, Roger. So I’m concerned about what Facebook knows, but over time there’ll be mergers, acquisitions, and with those mergers and acquisitions along goes my data. So while they may not today … iRobot, can’t they sell the data that it gathers from the Roomba vacuum cleaner that knows where my furniture is placed and whether my dog has soiled the carpet? They can’t sell that to someone else. They’ve said that they won’t do that. They could get acquired by another entity, maybe a Facebook, maybe an Apple. I mean, Apple will get into driverless cars, and as that aggregation occurs, that’s when the real sort of tipping of the scales, I think is also gonna occur in terms of concern with regard to what those terms of service do or do not allow the acquirer to do with that data. Which at this point, they’re liable to do anything they want with that data. Pretty much, as part of that acquisition.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, Tom, early in the book you made an interesting statement that businesses and institutions have have evolved, not to reduce friction, but to live off its heat. What do you mean by that?

Tom Koulopoulos: So, not to pick on the government, because I think government is trying very hard to eliminate much of its friction, but if you look at government, that is sort of the poster child for friction, right? We have processes, procedures, agencies put in place. Agencies to manage agencies, and all of these people are employed specifically to take care of things that the system cannot, in and of itself do. Friction is just a natural byproduct of any process. Mechanical, physical, it doesn’t make … It could be an algorithm, it could be waiting in line at the supermarket. All of these represent friction. It’s what stands between me and the final objective of walking out with a finished good. Using that finished good in some manner.

When we look around us, and when you put this lens on, it’s amazing how enlightening it is. You start to see friction everywhere. Everything that you do as a consumer, every interaction you have, whether it be over the phone, or in person has some degree of friction involved in it. And I think one of the primary benefits of these algorithms and intelligent machines and AI, is to help us eliminate that friction so that we can be more productive. We can achieve higher efficiencies. Not just for the sake of making the machines move faster, to produce more, but for the sake of allowing us as human beings to do things that we are inherently better at doing as human beings. Rather than just greasing the gears, we can actually be more innovative, be more creative, apply ourselves to bigger problems, more complex problems. And friction prevents us from doing that.

I will say, by the way, that I often wonder if what scares us most is, historically this has been the case. What scares us most is that we can’t imagine how humanity can be repurposed towards some higher good. Towards some more productive use of the human resources. But if you look back historically, whether it’s the Luddites taking sledge hammers to early textile looms or cab drivers worried about Uber, we do find ways to redeploy human capital. In ways that we couldn’t have imagined but which are frankly, a much better use. A much more meaningful use of human capital than they were in the past.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and you actually have a chapter that’s titled in part, The End of Friction, so you really have a positive outlook on that, and this is going to be the use of AI and other technologies to eliminate some of the annoying things that we have to put up now, and deal with other humans, and push people back and forth and so on?

Tom Koulopoulos: I’ll share with you an anecdote, I was at Macy’s headquarters a few years back, meeting with some of their execs, and we were talking at the … Terry at the time, their CEO, we were talking about retail and the friction in retail. And I had taken my son to go with me to New York City for this meeting. He wasn’t at the meeting but he was at Macy’s and I said, “Why don’t you go ahead?” Beautiful department store and he loves shopping, clothes shopping. But he had gotten Macy’s down to an art form. Because one of the things Macy’s would do with their loyalty program is issue oodles and oodles of coupons. So you would have in your account, you would have dozens of these coupons. Each one for a different percentage off, a different amount, a different type of item, and what he would do, is he would get these coupons, he would line himself up at the register with 10 different purchases. Not just one, but 10 purchases so he could maximize the discount potential of all these coupons.

And everyone in line behind him was having a fit, because they had to wait for him to go these 10 transactions. I-

Roger Dooley: It’s like the lady in the supermarket that has 50 paper coupons, although thankfully, those are getting a little more less common now.

Tom Koulopoulos: You got it. Exactly. But nonetheless, but we see this still. It manifests itself. Maybe in this case, Macy’s would do it all online. So you have to ask the question, why in the world could you not combine these online coupons, in the way that takes the burden off of the customer to be the super glue in figuring all this out? I shouldn’t have to game your system as a customer. You should help me figure out what is the most effective way to use these offers.

Roger Dooley: Well arguably, Tom, Macy’s wants to add a little bit of friction there, so the customers don’t do that. They figure, “Oh, geez. This is gonna be a real pain in the butt. I’m simply not going to deal with all that. I’ll use this good 35% coupon and forget the rest.”

Tom Koulopoulos: Unfortunately I think you may be on to something there.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. One little anecdote that you … You spent quite a bit of time on self driving cars and I’d be interested to hear why you focus quite as much on that because I think it’s an interesting story. But, one little element there that I hadn’t heard before was how self operating elevators finally got popular after being around since the turn of the last century. What’s the story there?

Tom Koulopoulos: Yeah, it’s not the first time we’ve gone driverless. People are surprised to hear this. We’ve become so accustomed to getting into an elevator that drives itself. You push the button. Today you don’t even do that. You push the floor that you’re going to before you get into the elevator and the elevator takes you to that floor. It optimizes the traffic that way. But we forget that up until the middle of the last century, 1940s thereabouts, elevators were driven. Whether you were in a department store or an apartment building, or an office building, elevators were driven by elevator drivers. There was an elevator drivers union. It’s funny because automatic elevators existed pretty much concurrently with the development of the elevator. It’s just that people would not get into an elevator without a driver. They didn’t trust the machine to do the job on its own.

And when you think about it, elevators can be a scary thing. You’re going up in high rise, you’re going up many floors. The thought of it can be trying to some people. It still is today. But there was a very large elevator drivers union strike in New York City that shut down the city, and it so upset people that finally landlords and business owners said, “We can’t be at the whim of the drivers. Let’s go to automatic elevators.” And they did. And in the course of about five years, every elevator driver was put out of business. I mean it makes Uber seem pale in comparison. Then today, of course you would never get into an elevator with a driver. You’d be terrified to do that. You’d be wondering if this human being can actually operate the elevator as well as the elevator can operate itself.

So, the point of that story is that so much of what we see as being safe is perception, what we perceive to be safe, based on what we’re accustomed to. And I think the same applies to driverless cars. We’re not accustomed to them right now. But I do believe that when we finally get to the point where we have driverless cars, we will have achieved something enormous in terms of our understanding of AI. Because it will be this watershed moment where we trust ourselves, our lives, our children, our parents to technology. In a very overt way, that up until now, I don’t think we’ve really experienced on that broad of a scale.

But here’s the beauty of it. Today, over a million people, 1.3 million people die every year in auto accidents. The numbers on injuries are fuzzy but at least, let’s say at least 10 times that many. And I’ve heard as much as 50 million people are injured somehow in auto related accidents. Ninety percent of that doesn’t have to happen. It’s human error. So we will get to a point, I have no doubt, and maybe 10 years, but certainly by 20 years time where we look back and say, “How in the world did we ever get into these automobiles and drive them ourselves, or allow them to be driven by human beings? That was so incredibly dangerous, unnecessary carnage.” And at that point, it won’t be much different than looking back on those drivers who drove elevators at one point in time. It’s amazing how society changes when behavior changes, and en masse we realize that we were really living in the dark ages all along and just didn’t know it, didn’t want to admit it.

Roger Dooley: So, Tom, jumping over to another topic, what do you mean by hyper-personalization? I know a lot of our listeners are into marketing and I think that are familiar with traditional personalization, and how do you see that evolving going forward?

Tom Koulopoulos: So the shift from personalization or customization to hyper-personalization is a fairly simple one. We’ve all become accustomed to goods that are somewhat customized to our desires. It could be an automobile with a certain color of interior, or a certain trim package. It might be a monogrammed item of clothing. Whatever it happens to be. We’ve become accustomed to those sorts of things. Hyper-personalization however, is personalizing an item to my needs without even asking me what my needs are. It’s understanding me so well that you can look into the future and say, “This is exactly what you need,” based on your behaviors. And now this is difficult to fully appreciate, because we really haven’t been there yet. We haven’t experienced that.

So, I like to use an analogy. Imagine that you have a personal shopper. Someone who really understands your tastes, your preferences, your size. Noticed that you put on a few inches, because you put on 10 pounds over the winter, or whatever the case might be. But you love your personal shopper because they make you look good. They anticipate what you need. You don’t have to tell them what you need, or at minimally give them some direction, and they’ll do the rest. I mean, who wouldn’t love that, right? So the idea of having, in a retail context, having hyper-personalization is having that personal shopper, but in this case they’re an algorithm, but not a person. And that algorithm knows you well enough to be able to project what you need, when you’ll need it. What fits you, what styles you enjoy.

It’s nothing more than being able to create a product experience that suits you as an individual, not as part of a demographic, or a market category, or an age range, or what have you. But as an individual. And the difficulty with this is that, Amazon’s trying to do this desperately. Google is certainly trying to do this in many ways. But Amazon’s the most visible player right now, because they make recommendations for us. The problem is that, they don’t have enough data on which to make those recommendations. Well my behavioral data is fairly narrow and shallow today. So, they’re trying their best with what they have, but it’s not yet hyper-personalization. Hyper-personalization’s really getting to that next step where you understand me, based on a much larger volume of behavioral data than what’s available today.

Once we get there, the value to me is enormous, because it gives me time that I would otherwise not have. I’d rather define my requirements. It provides an element of surprise. I get things that I wasn’t expecting to get, but which in fact I do need. So I’m not running off to the supermarket at the last minute to get something because I’m out of a certain ingredient. The AI knows me well enough to know that there are certain things that I will probably need, based on my recent behaviors and trends of behavior. That’s the kind of world that I see us moving into.

When you talk about that, a lot of people say, “Well boy, that’s creepy, Tom. But I mean, I don’t want someone to know me that well.” Perhaps, but once a few of us begin to see the value there, I think it will cascade very, very quickly. Because you’ll be at a severe comparative disadvantage because, frankly you won’t have as much time on your hands. You won’t be able to enjoy life as much. You’ll be wasting time. If we took the number of returns, merchandise returns that people make today and tallied them all up, it would be I think a number four or number five on the Force 500 of largest … Isn’t that crazy? So we return stuff because we buy stuff we don’t need.

What’s even worse, I love this term, closet of regret. My closet of regret. All of us have a closet of regret. We have these clothes that just don’t fit us. We bought them, we’re waiting to fit into them. They looked good online, or they looked good in the store. That’s insanity. We’re wasting money, we’re wasting resources. It’s horribly inefficient. So I think that once we experience that mode of hyper-personalization, we’ll never ever want to go back. And again, the analogy, the trite analogy, imagine having a personal shopper that knows you that well. By the way, if you tell your personal shopper just a little bit of data, you’re gonna have a lousy personal shopper. You have to tell him or her a lot about yourself. The more they know about you, the better they are as a personal shopper, and the same thing applies to AI.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I think just even without that much personal data, applying some AI to the process would help. Because I don’t mind it when Amazon say, recommends a new mystery title to me because they notice that I bought several mysteries in the past and there’s one from perhaps an author that I’ve read before. When they keep suggesting a suitcase, where you bought the suitcase three weeks ago and it’s not, it shouldn’t be a consumable. Sometimes they are but those are the ones that are annoying. Where no, I do not need that. And of course, you’re retargeted by ads the same way, that you keep seeing ads for stuff that you don’t need. But I think more data and better AI will fix that sooner or later.

Tom Koulopoulos: It’s horribly dysfunctional right now, because I remember specifically getting ads for Eclipse Glasses, months after the eclipse had happened last year, here in the Northeast. It’s ridiculous.

Roger Dooley: Algorithms gone wild.

Tom Koulopoulos: Exactly. Algorithms that clearly need some fine tuning here. But look, here’s the thing. I know for a fact that Amazon has as its goal, to create an experience for you where you will literally come home and find an Amazon box on your front step or in your house or wherever, that you hadn’t ordered. You will open it up, you’ll look inside and say, “Oh it’s exactly what I needed today.” That sounds again, it sound peculiar to us right now. But in the book, we talk about how peculiar even the Sears catalog was at the time to people, that were accustomed to buying things by going into their general store. And the reason they loved the general store, was because the store keeper knew who they were. And they couldn’t imagine buying out of a catalog from someone who didn’t know who they were.

Well, guess what? What we’re doing is going full circle. We never had … To scale the industrial era model of retail, we couldn’t know who you were. We had to work with large markets, large demographics. Large marketing budgets that were 50% useless. But of course as the saying goes, we didn’t know which 50%, right? Now we’ve come full circle. We’re back to that store keeper who really does know you, understands you, gets you. And if Amazon can send that box to me, and say, “You don’t have to pay for this. If you don’t want it, we’ll pick it up tomorrow. No worries.” Why wouldn’t I try that. And I think that’s what we’re on the precipice of, is seeing that degree of hyper-personalization where I begin to trust the brand because it’s being loyal to me. Not the other way around. I’m not brand loyal because I’m part of the Pepsi generation. It’s being loyal to me because it gets me, it understands me. And it respects who I am, and it does so in a way that’s respectful, not creepy.

Roger Dooley: Even if they didn’t go as far as having that package on your doorstep, which would be impressive if they were usually a good match for your needs, but even just saying, sending you an email in the morning, “Hey, we can have this product to you by noontime.” And you look and say, “Wow that’s something I really do want, because they made a wise choice.” It’d be slightly less creepy, and maybe even a little bit less expensive for them, just to have it staged nearby, rather than delivering it and having to pick it up. But no, we’ll get there probably sooner than we expect. One last question, Tom. Where do you fall in the danger of AI debate? Are you in the Musk camp that worries about AI taking over, you know killer robots and such, or are you more optimistic?

Tom Koulopoulos: So, we have to draw a firm line here, because it’s what we call narrow AI which we talk about in the book, and generalized AI. The difference reasonably put is, generalized AI can learn about whatever it wants to learn about. We’re not there, not even close to that yet. Today, AI learns what we tell it to learn about. So you can have an AI that can drive a car, or it can operate a machine, or it can play chess or it can play Go. But we point it in the direction and give it the data base that it has to use, the data set that it has to use, to understand to play that game, to operate that machine.

Generalized AI has curiosity. We have no idea what that means, to have curiosity as a machine. So, if we were up on that precipice, then I would share Musk’s concern, but we are not. He’s concerned about something which is much further out than anything we’re talking about right now in the present day. So am I concerned? We need to be vigilant. Every technology required vigilance. This was as true for nuclear weapons as it is for AI. So I think our vigilance is well placed. We need as a society to keep our eyes wide open, and to be vigilant. But at the same time, with every technology, all we have to do is make sure that the good, the positive, outweighs the negatives. It’s what we’ve done, from, everything from the wheel to the hammer, to the nuclear, to the splitting the atom. They’ve all been a matter of creating more benefit than we create harm. That’s what technology does.

Technology’s apolitical. It doesn’t take sides. We take sides. So we need to be sure that we’ve been vigilant and that we keep our eyes open. I think the best thing we can do is make sure we create more positive good, which is what we try to do with the book, is point out what the positives are. What the value is of this. If we focus on value creation, guess what? The bad stuff will happen. The nation states, the terrorists, the bad people will do bad things with technology. Always been the case. But we’ll do more good with it, and that to me is what’s more important.

Roger Dooley: Great, well that’s a good positive note to wrap up there with, Tom. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with, Tom Koulopoulos, author of Revealing the Invisible: How Our Hidden Behaviors Are Becoming the Most Valuable Commodity of the 21st Century. Tom, how can people find you and your ideas online?

Tom Koulopoulos: My Twitter handle is TKSpeaks. That’s usually the easiest way to get ahold of me. I’m pretty active on Twitter. And the website for the book is, revealingbook.com. Revealingbook.com and folks can get to me through the website or through Twitter @TKSpeaks.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will link to those places, and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. And we’ll have a text version of our conversation there, too. Tom, thanks for being on the show.

Tom Koulopoulos: Roger, it was my pleasure. Thank you.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at https://rogerdooley.com.